Where will medicine and especially space medicine be in ten years from now? What questions will have been answered, what problems associated with preventing, diagnosing, and treating illnesses will have been solved? What will be the contribution made by space medicine? Forecasting scientific progress is difficult, even almost impossible, because many of the most significant scientific breakthroughs are based on chance discoveries or experiments.

The specificities of the space environment have led to the development of a new medical specialty, termed “space medicine”. The expression was first coined in 1948 by the German physician and physiologist Hubertus Strughold who became the first Professor of Space Medicine at the School of Aviation Medicine (SAM) at Randolph Air Force Base, Texas. Space medicine is a subspecialty of focus that aims to maintain human health and performance in the extreme environment of outer space based on scientific knowledge concerning the aerodynamic effects on the human body. In this context, space medicine is a subspecialty of focus that aims to maintain human health and performance in the extreme environment of outer space based on scientific knowledge concerning the aerodynamic effects on the human body.

Space medicine, as a distinct field, was still in its infancy five decades ago. Scientists studying the effects of space travel on the human body have begun to appreciate the relevance and possibility of future discoveries in the field. Major innovations in healthcare, including insulin pumps and cochlear implants, are a result of space medical research. Specifically, practical questions of high-altitude, climate, diving, sport, and occupational medicine, as well as rehabilitation and even isolation research are subjects of interest (e.g., osteoporosis, cardiovascular illness, countermeasures, and exercise regimes).

Space medicine research thus extends far beyond the narrow realm of space physiology and space medicine: it is an advanced preventive medicine in its best sense. Space medicine and space physiology are often viewed as two aspects of space life sciences, with the former being more operational, and the latter being more investigational. Space medicine tries to solve medical problems encountered during space missions. These problems include some adaptive changes to the space environment, including weightlessness, radiation, the absence of the 24-hour day/night cycle; as well as some non-pathologic changes that become maladaptive on return to Earth, such as muscle atrophy and bone demineralisation. Space physiology tries to characterise body responses to space, especially weightlessness, reduced activity, and stress. It provides the necessary knowledge required for an efficient space medicine. Space physiology is as old as the first flight of humans in a hot air balloon, when the symptoms of hypoxia were first discovered (at the expenses of the life of the pilot). The interest in this field of research kept growing along with the space program and the opportunities it provided for flying more and more humans in space on board capsules, shuttles, space stations and soon suborbital space planes. The future of human space flight will inevitably lead to human missions to Mars. These missions will be of long duration (30+ months) in isolated and somewhat confined habitats, with the crew experiencing several transitions in levels of gravity, dangerous radiation, and the challenges of landing and living on their own on another planet. Many research questions must be addressed before safely sending humans to explore Mars, when our current knowledge on humans in space does not exceed 14 months in only one individual. A human research roadmap for tackling these research questions has been recently detailed by NASA.

Depending on their mission, spacecraft may spend minutes, days, months, or years in the environment of space. Mission functions must be performed while exposed to high vacuum, microgravity, extreme variations in temperature, and strong radiation.

Another important environmental attribute of space is microgravity, a condition achieved by the balance between the centrifugal acceleration of an Earth-orbiting spacecraft and Earth’s gravity. This condition, in which there is no net force acting on a body, can be simulated on Earth only by free fall in an evacuated “drop tower.”

A space suit is a complete miniature world, a self-contained environment that must supply everything needed for an astronaut’s life, as well as comfort. The suit must provide a pressurised interior, without which an astronaut’s blood would boil in the vacuum of space. The consequent pressure differential between the inside and the outside of the suit is so great that when inflated the suit becomes a distended, rigid, and unyielding capsule. Special joints were designed to give the astronaut as much free movement as possible. The best engineering has not been able to provide as much flexibility of movement as is desirable; to compensate for that lack, attention has been directed toward the human-factors design of the tools and devices that an astronaut must use. In addition to overcoming pressurisation and movement problems, a space suit must provide oxygen; a system for removing excess products of respiration, carbon dioxide and water vapour; protection against extreme heat, cold, and radiation; protection for the eyes in an environment in which there is no atmosphere to absorb the Sun’s rays; facilities for speech communication; and facilities for the temporary storage of body wastes. This is such an imposing list of human requirements that an entire technology has been developed to deal with them and, indeed, with the provision of simulated environments and procedures for testing and evaluating space suits.

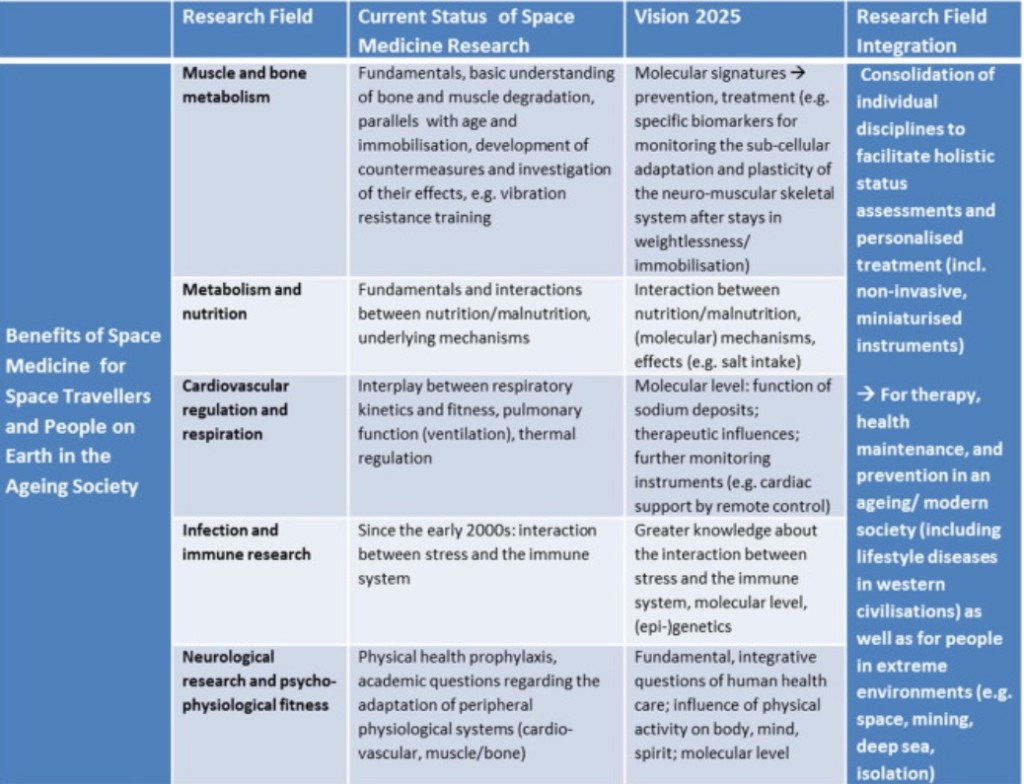

Until 2025, space medicine will have contributed towards perceiving a human being as an integrative system, considering the complex interplay of all aspects of the process of ageing, and effectively developing measures of prevention, health preservation, and rehabilitation for patients on the ground as well as for astronauts on long-term missions. In this sense, space medicine should exert its pioneering role and accompany and stimulate the expected paradigm changes in terrestrial medicine that are necessary to cope with the global care changes of our ageing societies (for an overview, see Fig. 1).

The effects of space flight conditions on the autonomic nervous system should be at the origin of two medical issues experienced by a significant number of astronauts. These issues are space motion sickness immediately after entering weightlessness or after returning to Earth’s gravity, and post-flight orthostatic intolerance. Due to shared neural pathways, clinical treatment of one condition often interacts with the other condition.

Link to NASA’s Human Research Roadmap answering some of the questions expressed on the 4th paragraph:

http://humanresearchroadmap.nasa.gov/

Links:

Space medicine 2025 – A vision, A roadmap for incorporating space medicine into the strategic plans of the Saudi space commission, Space medicine 2025 – A vision, Patents in space medicine: An immediate call for innovations in the field, Space Physiology, Space, https://www.britannica.com/science/aerospace-medicine