An Example and a Review of the Gender Discrimination Bias and Health Inequalities in Nepal

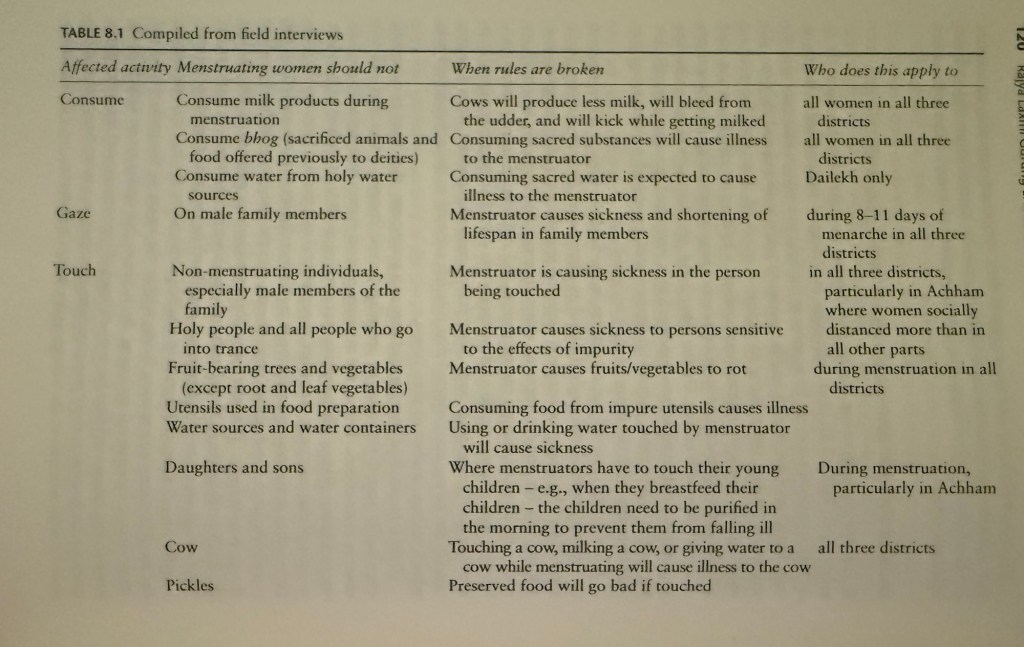

Chhaupadi is the practice of sending women to live in ‘period sheds’ which translates to the Nepali words ‘chhau goth’ while they are starting the menstrual cycle or going through it. Chhaupadi is a word derived from a combination of two words in the local Raute dialect spoken in Accham: chhau-menstruation and padi-woman. One of the major causes of death is reported to have been from inhaling the smoke from lighting the fires. This continues for atleast 4 nights but in some regions of Nepal the women have to stay for 7 days this number can vary and can go upto 11 days. “These huts are small, barely four feet high and six feet wide, hardly big enough for one person to sleep inside. They are made from locally available materials, such as wood, mud, or stone. Most huts do not have doors, which leaves menstruating women vulnerable to sexual predators and wild animals.” Since they are built without windows there is limited ventilation. In fact, the beliefs and customs are not just connected to Hinduism but also to the local god Masto. Women are not allowed to enter their own homes as they are considered “impure” and “unclean.” Dhami is a local shaman and in the village he’s considered to be a mediator between the common people and God and spirits. The menstruating women can neither enter their homes nor touch their husbands and are forbidden from doing any work and even their clothes were considered as “polluting”. Menopausal women would refrain from physical contact as they are now considered pure. The Kumaris continue this legacy of promoting the ideology that women should and continue to remain untouchables by society as being a woman, menstrual activities all together are not a part of the cycle of life; birth, growth and development and nurturing but something far malicious and sinister, something that we must be feared upon. ‘Nachhune hune’ means not-touchable and ‘para-sarne’ translates to stay far away.

Resistance to comply would anger the family members, village elders, and most importantly the Dhami who could be a man or a woman. Based on the interviews conducted the Brahman Chhetri group were most likely to strictly follow the rules of chhaupadi but the other groups including the lower caste women were involved too. The 3rd generation of women in the household look down upon their grand-daughters for having a more loose/laid back approach towards the rules as that applies to everyone. The Nepali government has made a law criminalising the chhaupadi practice, societal pressure refuses a change. “This newly amended law has been in force since September 2018. The law stipulates that if people who observe chhaupadi are reported, they can be sentenced to three months in jail and a fine of NRs. 3,000 (Adhikari 2020).”

There’s a brief statement in schoolbooks stating that “…women and girls should stay outside the home during menstruation.” It’s not just a gender discrimination bias but an inequality and inequity to health access in a low-income country. “The law was enacted in late December 2019 with the case of Parbati Buda Rawat.”

However, it took Nepal until 2018 to categorise the enforcement of chhaupadi practice on a woman as a criminal offence that became then punishable by three months of imprisonment and/or a 3,000 Rs. fine. In 2019 the Nepal police made its first arrest under the new law. The brother-in-law of a woman who died from smoke inhalation in the confined space of a “chhau goth” was arrested in Achham for banishing his sister-in-law to a chhau goth (Ghimire 2019).

‘Dignity kits’ are distributed by INGOs, NGOs and local women’s organisations and vary in quality and content. The pad holders are typically made from soft cotton with a press-stud fastener to hold it in place with a set of absorbent liners. The holders have an inner waterproof, anti-bacterial liner and can be cleaned with soap. These are usually provided as part of a kit, with one or two pad holders, several liners, soap and a carry bag. Some kits include underwear (panties), and others have small bags to store the used pads in until they can be washed. When washed and dried correctly, pads can be used for up to three years (Days for Girls 2016).

One of the best-known global organisations operating in Nepal is Days for Girls (D4G), which started as a volunteer-run organisation in 2008 and has a network of over 70,000 volunteers globally making and donating menstrual kits. These kits are made overseas are in the main donated to communities in the ‘Global South’ as part of outreach activities by NGOs, social enterprises, or menstrual activists. D4G has also produced an educational flip chart, which it recommends is used when the kits are distributed to communities. D4G has also moved into producing the kits in the country by running training courses and has moved towards supporting enterprises in the country whilst maintaining their volunteer networks (Days for Girls 2016). Many organisations and individuals making and distributing kits have received training from D4G, although this can be expensive, whilst others have developed their own kits and educational material. The anti-fungal inner plastic lining, integral to the D4G products, is used by many of the organisations; however, due to lack of availability, tent material affected the comfort and functionality of the kits and, hence, their popularity.

Menstrual discrimination is a state of taboos, stigma, shame, abuse and restrictions associated with menstruation throughout the life cycle of menstruators. DM (Dignified Menstruation) is defined as a state of freedom from any form of taboos, stigma, shame, abuse, restrictions, or discrimination associated with menstruation throughout the lives of menstruators. Often, the words ‘menstrual dignity’ and ‘dignified menstruation’ are used interchangeably.

During the celebration of NHM day on May 28, 2020, the Ministry of Women and Children issued a set of 12-point declaration that included a number of elements, including the distribution of products but also endorsement of policies and continuation of campaigns, as well as mainstreaming plans and building on multi-sector, multi-agency partnerships.

For DM day, December 8, 2021, the global summit was conducted under the theme “Dignified menopause is a human right not a privilege,” along with Helen Kemp (Scotland) and Sarah Williams (England). The speakers were from all around the globe. The day was inaugurated by the honourable state minister from the Ministry of Health and Population from Nepal. In Nepal, the National Women’s Commission organised programmes in which representatives from commissioners (Dalit, Indigenous, Inclusion) addressed the programme, as well as launched a book titled ‘Surgical Menopause.’

Source: Menstruation in Nepal, DIGNITY WITHOUT DANGER.