“Aztecs were brilliant scientists, writers, and artists. Medicine is an example of their scientific activities. They developed ideas about the causes of illness, practical and supernatural. Priests and priestesses were involved in curing, but Aztecs had an array of healers. The most commonly used term by Aztecs for a doctor – someone with specific and practical knowledge about healing – was “ticitl,” female and male. That Aztecs wrote is not widely recognised.”

“Human sacrifice, particularly by offering a victim’s heart to Tonatiuh, was commonly practiced, as was bloodletting. Closely entwined with Aztec religion was the calendar, on which the elaborate round of rituals and ceremonies that occupied the priests was based.”

Two deeply rooted concepts are revealed by these myths. One was the belief that the universe was unstable, that death and destruction continually threatened it. The other emphasised the necessity of the sacrifice of the gods. Thanks to Quetzalcóatl’s self-sacrifice, the ancient bones of Mictlan, “the Place of Death,” gave birth to men. In the same way, the sun and moon were created: the gods, assembled in the darkness at Teotihuacán, built a huge fire; two of them, Nanahuatzin, a small deity covered with ulcers, and Tecciztécatl, a richly bejewelled god, threw themselves into the flames, from which the former emerged as the sun and the latter as the moon. Then the sun refused to move unless the other gods gave him their blood; they were compelled to sacrifice themselves to feed the sun.

Evidence that the Aztecs practised surgery is as follows:

“The history of Mexican surgery is deeply rooted in ancient Mesoamerican culture and practice. From a close review of the texts available, it was determined that the Aztecs not only had a developed method of surgical practice that served a variety of uses but also that the Aztecs, as the culmination of Mesoamerican civilisation, contributed to the modern practice of surgery.”

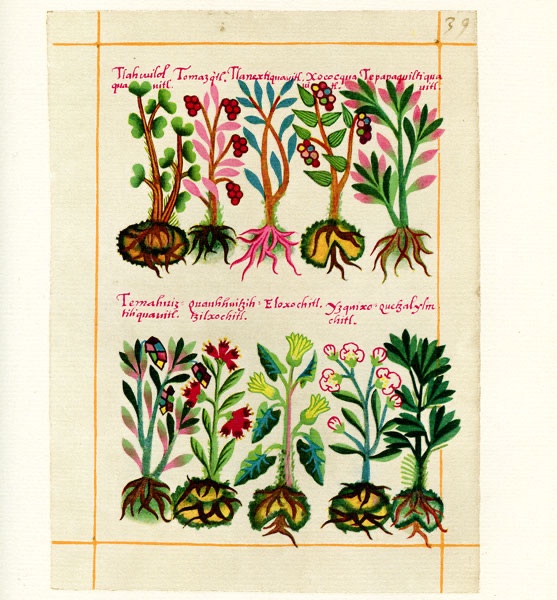

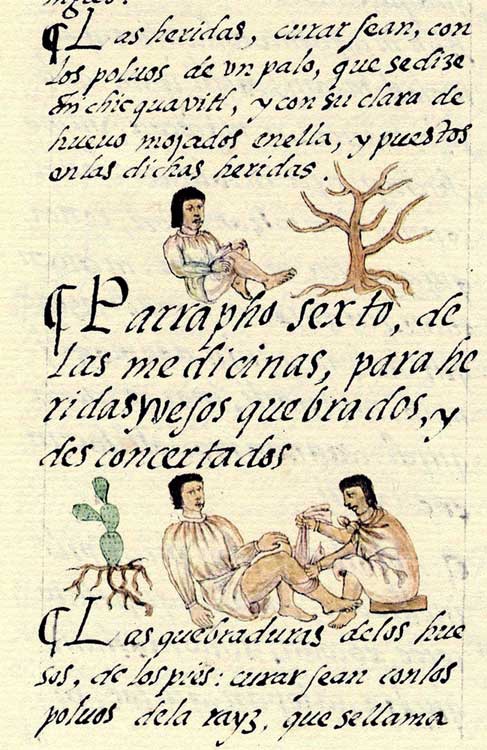

Two texts are of significant importance to this investigation and serve as a testimony to the accomplishments of the Aztec nation. The first is the Florentine Codex, compiled by Fray Bernardino de Sahagún, titled The General History of the Things of New Spain (1540-1585). The second is the Badianus Manuscript, or the Codex Barberini (1552), compiled by Aztec physician Martín de la Cruz and translated to Latin by Juan Badiano. Surgical procedures varied greatly from setting fractured bones, orthopaedics, draining abscesses and reconstructing wounds to burn treatment, ophthalmological procedures and human sacrificial mutilation. Perhaps one of the most significant contributions to modern surgical practice is the procedure for therapeutic arthrocentesis. Human hair and cactus fibres were commonly used as sutures with cactus or bone needles. It was observed that Aztec physicians practiced interrupted suturing and considered inflammation as a disease process not necessarily related to healing. Aztec surgeons used traction and counter-traction to reduce fractures and sprains, and used splints to immobilise breaks, as did their European counterparts. Aztec surgeons were some of the first to practice intramedullary fixation, using wooden pegs as intramedullary nails to reunite the pieces of bone in a break. The Aztec contributions to modern medicine and specifically to modern surgery are visible in several modern practices, most notably in the practices of arthrocentesis and fracture repair.

There was also a remarkable amount of pharmaceutical interventions in use;

‘King Philip II of Spain sent Francisco Hernández, one of his royal physicians, on a scientific mission to the New World. Hernández was directed to make a comprehensive study of the medicinal plants of New Spain and Perú including their use, how and where they grew, and an estimate of their effectiveness. The magnitude of the task was so great that, even though the viceroys were ordered to assist Hernández in his work, he never managed to get to Perú (Somolinos d’Ardois 1960: 144-152). Hernández interrogated native physicians and did his own evaluations according to the Galenical theory current in Europe at the time. The massive original version of his book, describing Aztec medicinal plants, minerals, and animals, with its irreplaceable native illustrations, was destroyed in a fire at the royal palace in 1671. What we now have is an incomplete copy made in 1648 (Somolinos d’Ardois 1960: 282) Hernández was full of praise for the extent of botanical and taxonomical knowledge of the Indians:-

Sadly Hernández’s original great work ‘The Natural History of New Spain’ was never published; some of the studies based on his work are inevitably incomplete.

‘“I marvelled, in this and in innumerable other herbs, which are nameless among us, how in the Indies, where people are so uncultured and barbaric, there are so many herbs, some with known uses and some without, but there is almost none, which is not known to them and given a particular name” (Hernández 1959-1984: vol. 5, 425).

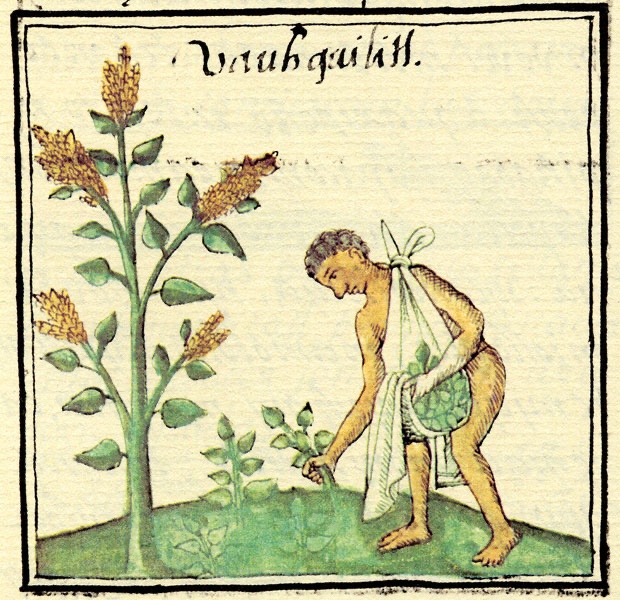

Although, as in many other medical systems, including our own, illnesses were treated by imploring the gods and using magical remedies, the Aztecs also had knowledge based on research and experience. The Aztecs had considerable empirical knowledge about plants. The emperor Motecuhzoma I established the first botanical garden in the Fifteenth Century and as the Mexica (the Aztec group that ruled in Tenochtitlan, now Mexico City) conquered new lands, specimens were brought to these and other botanical gardens. Natives of newly conquered areas were also brought to tend plants from their areas. Among other things these gardens were used for medical research; plants were given away to patients with the condition that they report on the results. These activities are reflected in the Aztec’s extensive and scientifically accurate botanical and zoological nomenclature (Ortiz de Montellano 1984). The Spanish chroniclers were impressed with Aztec medical knowledge. Torquemada (1975-1983: vol. 3, 325) mentioned that Aztec battle surgeons tended their wounded skilfully and that they healed them faster than the Spanish surgeons. He also described the infinite number of herbs sold in their markets, the skill needed to distinguish between them, and that they cured without using mixtures of herbs (1975-1983: vol. 3, 349). Motolinía wrote:-

‘“They have their own native skilled doctors who know how to use many herbs and medicines which suffices for them. Some of them have so much experience that they were able to heal Spaniards, who had long suffered from chronic and serious diseases”(Motolinía 1971: 160).

‘An area in which the Aztecs were clearly superior to the Spanish conquerors was in the treatment of battle wounds European wound treatment at that time consisted of cauterisation with boiling oil and reciting prayers, while waiting for infection to develop the “laudable pus” that was seen as a good sign (Forrest 1982). The Aztecs were engaged in warfare practically all the time and had developed a regime consisting of washing the wounds with fresh urine (a sterile solution), applying an herb to stop the bleeding, and using Agave sap with or without salt to prevent infection and promote healing. Judy Davidson and I (1984) showed that Agave sap was, in fact, antibiotic. A group of Argentinian surgeons used granulated sugar (which worked by the same mechanism as Agave sap) in successfully treating and preventing infections (Herszage, Montenegro, and Joseph 1980).

‘In my own studies (Ortiz de Montellano 1990), I have shown that the Aztecs could produce the physiological effects (vomiting, diaphoresis, etc.) that their ideas about the cause and cure of disease would require in over three fourths of their remedies. Evaluating the effectiveness of these remedies in our own terms, I found that only 22 percent were completely ineffective and that more than half had ingredients that had been shown to be effective, either by widespread use in folk medicines, in animal or laboratory tests, and even in clinical trials. This kind of track record has led the Mexican government to sponsor research on the validity of Mexican folk remedies for many years. The success of qinghaosu, the traditional Chinese antimalarial that has become a front-line remedy for that terrible disease, should encourage us to continue investigating the remedies used by the Aztecs.

Although my focus so far has been on remedies for disease, we should remember that health involves much more than curing disease after it occurs. Preventing disease and illness is as or more important than curing disease. Maintaining health involves eating a healthy and varied diet- the Aztecs ate a high fibre, low cholesterol, and very varied diet (practically anything that flew, crawled, or swam); exercise – there were no beasts of burden or wheels (humans had to carry everything), and public health measures – the Aztecs had provisions for clean water and floating ”honey wagons.”

We know the Mexica were excellent surgeons, and health practitioners in general – the Spanish admitted as such, and learned a lot from them too.

The best authority on this, without doubt, is Professor Bernard R. Ortiz de Montellano (he’s on our Panel of Experts), and we can do no better than quote from his superb book Aztec Medicine, Health and Nutrition. Here’s what he wrote in the chapter ‘Curing Illness’ –

The Aztec treatment of bone injuries was… possibly the most advanced aspect of Aztec surgery… They used traction and counter-traction to reduce fractures and sprains and splints to immobilise fractures… They also treated complications such as swelling around the break, incising it with an obsidian lancet [blade] or applying a mixture of plants as a plaster. For failure of the bone callus [bridge] to consolidate in fractures ‘the bone is exposed; a very resinous stick is cut; it is inserted within the bone, bound within the incision, covered over with the medicine mentioned’ [Florentine Codex – see pic 1]. [The medical historian] Viesca Treviño called this ‘a simple and unpretentious description of an intramedullar nail – a technique not used in Western medicine till the twentieth century.’

Intramedullary nails (IMNs) are the current gold standard treatment for long bone diaphyseal and selected metaphyseal fractures. Intramedullary nailing is the standard operative treatment of diaphyseal tibial fractures. It is also used effectively in treatment of nonunions of the tibial shaft. Modern nail designs have better distal locking options and the nails can be used in more distal fractures and nonunions.An advantage of intramedullary nailing is that it may be done with less soft tissue disruption than plating, depending on the degree of deformity and the presence of prior instrumentation.

We now know that obsidian (see pic 3), a volcanic glass, is one of the sharpest natural materials in the world, its edges thinner and sharper than modern surgical steel. This gives it an advantage even today in delicate cataract surgery, in which ‘the thinnest incision is desired’.

Writing in 1615 the Spanish Dominican friar Tomás de Torquemada mentioned that Aztec battle surgeons tended their wounded skilfully and healed them faster than did the Spanish surgeons. As Ortiz de Montellano explains, ‘one area of clear Aztec superiority over the Spanish was the treatment of wounds…’

The three steps of treatment were: 1) wash the wound with warm, fresh urine; 2) treat with [the herb] matlalxihuitl (Commelina pallida) to stop the bleeding; and 3) dress the wound with hot, concentrated sap obtained from Agave leaves, with or without added salt. Treatment was repeated if inflammation indicated infection was present.

Clearly, as the Aztecs were regularly at war with neighbouring tribes, they had plenty of opportunities to practice and develop their skills!

Sources:

https://www.britannica.com/topic/Aztec-religion

https://www.mexicolore.co.uk/aztecs/ask-us/what-type-of-surgery-did-the-aztecs-practice

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8567815/