In 1961, mental health services began with one mental hospital with two psychiatrist doctors.

The history of mental health care development in Nepal is around 60 years. The burden of mental health issues is high and resources are limited. Though there has been steady improvement in mental health care services, Nepal faces challenges similar to other lower middle income countries and some unique ones. The major challenges in mental health care in Nepal are high treatment gap, unregulated help seeking pattern, poor fund and research, inadequate and inequitable manpower, huge out of pocket expense, poor referral system, poor mental health literacy, high stigma, non-judicious prescribing and various administrative difficulties.

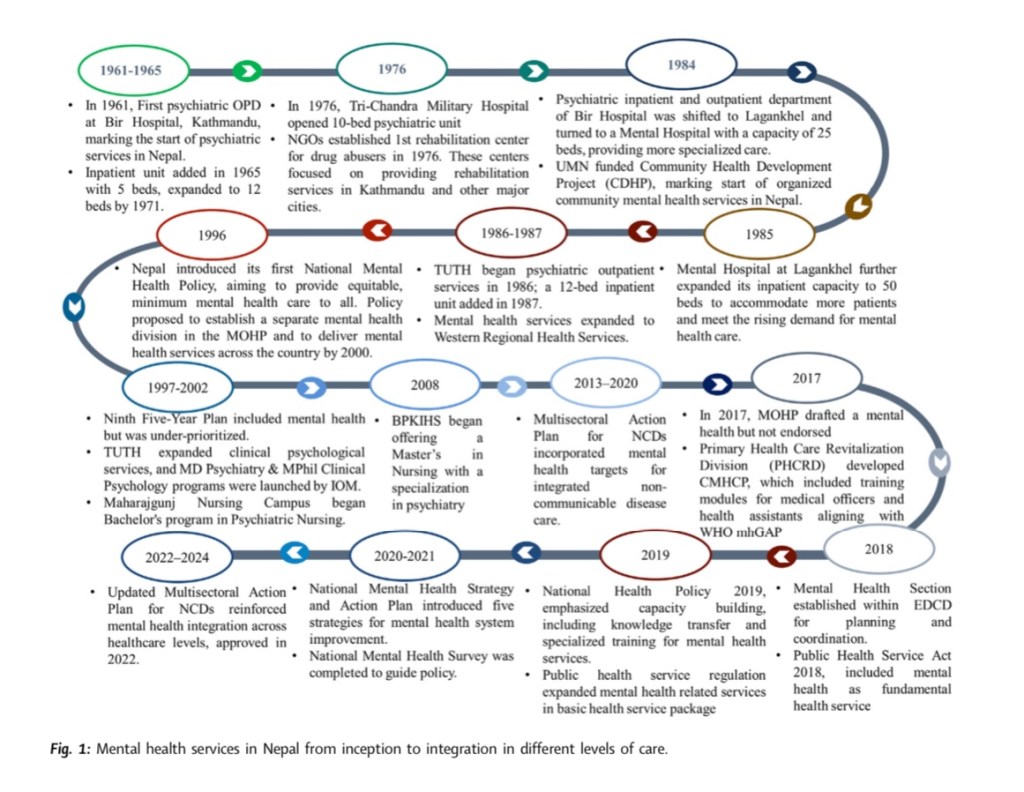

The modern mental health system in Nepal is based on allopathic medicine, which was established in the mid-20th century along with outpatient mental health services in Bir Hospital (1961), which was later increased to five-bedded inpatient service in 1965 and was further strengthened to 12 beds in 1971.

Eleven years after the first mental health service in Nepal, Tri-Chandra Royal Army Hospital started a 10-bedded neuropsychiatric unit. After the first establishment of rehabilitation centre for Nepalese drug abusers in 1976 by Father Thomas Gaffney, several nongovernmental organisations (NGOs) started working in the field of mental health and drug abuse in 1983–1984. In 1984, after the separation of 12-bedded psychiatry department in Bir Hospital, an independent mental hospital was established in 1985, which was then shifted to the current location at Lagankhel, Lalitpur, Patan. In due course of time, mental hospital beds were gradually increased to 25, then to 39, and finally to reach the current capacity of 50 beds. This is the only central government hospital that solely provides tertiary-level mental health care in Nepal.

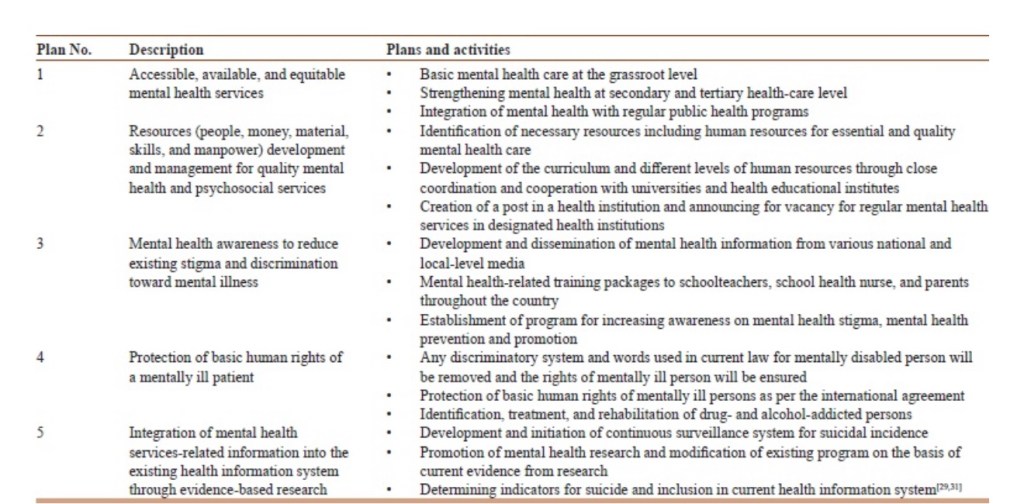

Five-year plan, 2019–2024

Nepal’s current 5-year plan embraces mental health care and plans to expand access to basic mental health care at all levels of the health-care delivery system to preserve and maintain the right to mental health for all citizens.

However, in many developing nations, including Nepal, mental health re-mains overshadowed by other health priorities. With limited health budgets, governments often struggle to meet the comprehensive health needs of their population and focus primarily on prevention and treatment of physical diseases and infections, neglecting the resources for mental health and well-being. As a result, a significant treatment gap persists for mental disorders globally, with four out of five people having mental health problems in lower-income countries deprived of effective treatment. For instance, a survey across 14 countries found 76.3%–85.4% of those with severe mental disorders in low-and middle-income countries (LMICs) do not receive any treatment.

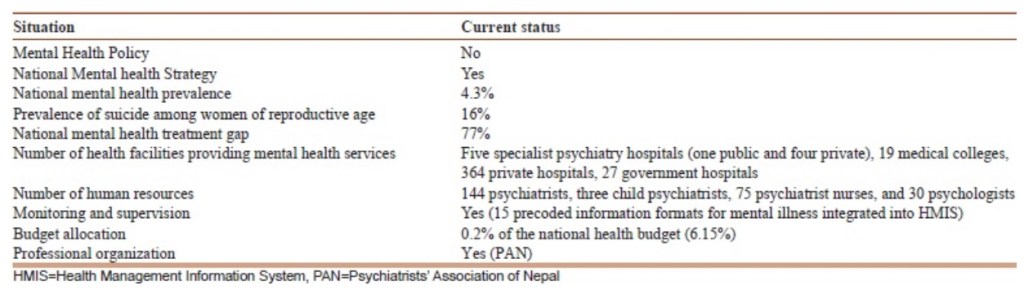

Current situation of mental health in Nepal

The WHO’s health system framework describes health systems in terms of service delivery, health workforce, information, medical products, vaccines and technologies, financing, and leadership/governance. Each building block represents a core function vital for an effective and equitable health system and provides a holistic approach to analysing health systems for functionality, efficiency, and equity. This framework is particularly suitable for LMICs like Nepal, as it highlights systemic gaps and provides a basis for strategic planning and policy reform.

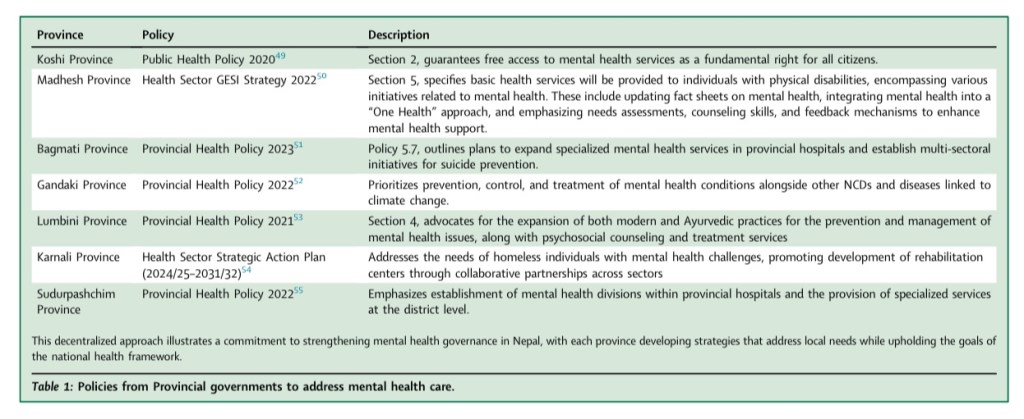

The updated Multi-sectoral Action Plan for NCDs (2021-2025), also reinforced mental health services within all healthcare levels. Despite these advancements, there is a lack of clear accountability framework and leadership within the mental health sector, which hampers the effective implementation of policies and plans. Furthermore, coordination between federal, provincial, and local government levels, as well as across different sectors such as health, education, and social services, remains weak, affecting the integrated delivery of mental health services.

To address the service gap, the MoHP developed and implemented the Community Mental Health Care Package 2017, which integrates mental health services into primary care in alignment with the mhGAP. This model aims to manage common mental health disorders, including depression, anxiety, alcohol use disorder, and child and adolescent mental and behavioural disorders at the primary care level.* Furthermore, the MoHP has made a mandate that general hospitals with over 200 beds should establish functional mental health units. In 2022, the “Khulla Mann” District Mental Health Care Program was introduced to build upon and replace the 2017 Package.

The “Khulla Mann” program aims to enhance primary mental health services through a people-centered needs-based approach by integrating mental health care into district hospitals, Primary Health Care Centres (PHCCs), and health posts, while linking them with community resources to promote mental health equity. However, Nepal faces a severe shortage of psychiatrists, making nationwide deployment unfeasible and potentially compromising service quality.

A more practical interim strategy in the current context could be as suggested by Upadhaya and colleagues (2017), which involves a task-sharing approach where trained primary healthcare workers manage mental health medications and provide counselling services, as recommended by mhGAP.* This can be further supported by telemedicine and mobile health (mHealth) interventions to reach underserved populations. However, this should be a temporary measure until Nepal produces sufficient numbers of specialised mental health professionals, such as psychiatrists and psychologists.|

To strengthen Nepal’s mental health information system, it is crucial to enhance health workers’ capacity in diagnosis and reporting, standardise data collection, and conduct regular data reviews to ensure accuracy and completeness. Addressing the observed challenges is crucial for building a more robust health information system that can better support the planning, implementation, and evaluation of mental health services across the country.

Despite ongoing efforts to strengthen human resources and integrate mental health services into primary care, sustainability and nationwide coverage remain challenging. There is a need to further institutionalise these initiatives by addressing workforce shortages, improving capacity-building mechanisms, and ensuring their integration at all levels of care. Additionally, a dedicated Mental Health Section within the health system, which would focus exclusively on mental health operations, policy execution, and program monitoring, would further help in strengthening the mental health service advocacy and support system. Establishing such a section would not only streamline mental health governance but also necessitate the recruitment of mental health-specific workforce to support strategic planning, coordination, and service delivery improvements.

Mental health problems are often viewed in a more isolated manner than physical problems and remain stigmatised in many societies, leading to treatment delays that can result in severe outcomes. Stigma and misconceptions about mental illness persist, with many attributing it to supernatural causes. Nepal, like many low-income and middle-income countries, grapples with significant disparities in healthcare access and quality, which are particularly pronounced in the realm of mental health services.

The Psychiatrists’ Association of Nepal (PAN) is the only nonprofitable professional organisation of Nepalese psychiatrists established in 1990. PAN has been taking a leadership role in the development and implementation of national mental health programs and policies. PAN issues the “Journal of Psychiatrists’ Association of Nepal” twice a year. It also organises national and international workshops and conferences on various themes related to mental health.

There were only two psychiatrists in the initial phase of mental health service. But now, the current human resources have been expanded to 144 psychiatrists as well as three superspecialty child psychiatrists. Out of these, 34 and 110 psychiatrists work in public and private sectors, respectively. There are also 75 psychiatric nurses and 30 psychologists working in private practice. Most of the psychiatric manpower is concentrated in urban areas.

Additional info:

On further reading

https://www.lidsen.com/journals/geriatrics/geriatrics-08-01-268

Sources:

https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-981-99-9153-2_6

https://www.nepjol.info/index.php/mjmms/article/download/71232/54305/207462