‘Thanks to K-MEDI’s expertise and RIGHT Foundation support, we are hopeful we can deliver urgently needed treatments to the millions of people affected by river blindness. We need to address the gap in current treatments, and developing effective, targeted test-and-treat approaches with macrofilaricidal drugs like oxfendazole will be critical in reaching the WHO’s goal of eliminating this terrible and debilitating disease.’

~Dr Luis Pizarro, Executive Director of DNDi

K-MEDI hub and the Drugs for Neglected Disease initiative (DNDi) have collaborated together in efforts to develop a treatment for onchocerciasis, the second leading cause of blindness after trachoma. Onchocerca volvulus is a type of roundworm called a filarial worm. There are 19 million people infected by the roundworm and this includes the 1.15 million people who have lost their eyesight!

DNDi will be the principal investigator and K-MEDI is the collaborative institution. This R&D initiative is supported by the Research Investment for Global Health Technology Foundation (RIGHT Foundation), with a total of KRW 3.2 billion (approx. EUR 2.2 million) over a period of 2.5 years. Established in 2003 by Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF), Institut Pasteur, and four leading medical research institutes in neglected disease-endemic countries, DNDi is a non-profit international research organization dedicated to developing new treatments for neglected diseases. The molecule oxfendazole is going to be a safe, an effective, an affordable and a globally accessible treatment for the filarial worm.

The RIGHT Foundation is the first international public-private partnership funding agency in Korea, jointly established in 2018 by the Ministry of Health and Welfare, the Gates Foundation, and Korean life science companies. It supports R&D projects that help alleviate the disproportionate burden of infectious diseases on low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), thereby contributing to global health equity. To date, the foundation has supported 70 research projects with a total funding of 107.7 billion KRW.

For context…

Onchocerciasis is the second leading cause of infectious blindness worldwide (after trachoma).

Onchocerciasis is most common in tropical and sub-Saharan regions of Africa. Small foci exist in Yemen and along the Venezuelan border with the Brazilian Amazon. Blindness due to onchocerciasis is fairly rare in the Americas; Colombia, Ecuador, Mexico, and Guatemala have been declared free of onchocerciasis by the World Health Organization (WHO). People who live or work near rapidly flowing streams or rivers are the most likely to be infected. In addition to residents, long-term travelers (eg, missionaries, aid workers, field researchers) are at risk.

Pathophysiology of Onchocerciasis

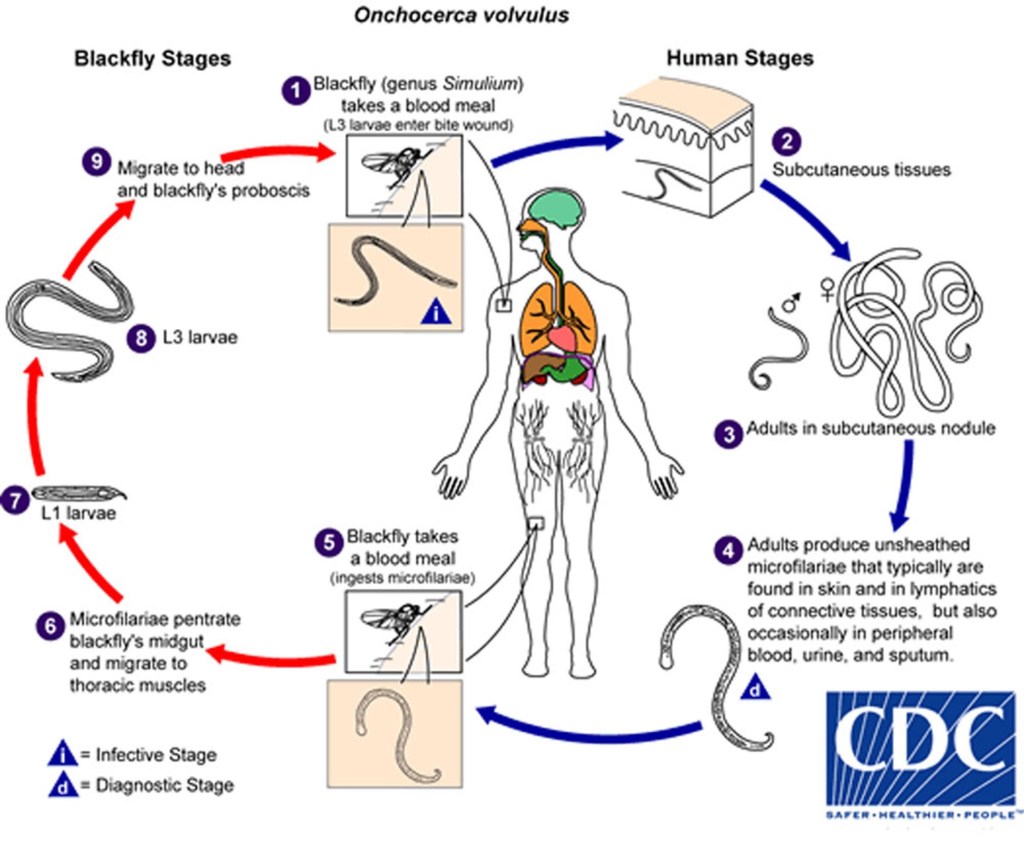

Onchocerciasis is spread by female blackflies (Simuliumgenus) that breed in swiftly flowing streams (hence, the term “river blindness”). Many blackfly bites are needed before disease develops. Infective larvae inoculated into the skin during the bite of a blackfly develop into adult worms in 12 to 18 months. Adult female worms may live up to 15 years in subcutaneous nodules. Females are 33 to 50 cm long; males are 19 to 42 mm long. Mature female worms produce microfilariae that migrate mainly through the skin and invade the eyes.

Symptoms and Signs of Onchocerciasis

Onchocerciasis typically affects

- Skin (nodules, dermatitis)

- Eyes

Nodules

The subcutaneous (or deeper) nodules (onchocercoma) that contain adult worms may be visible or palpable but are otherwise asymptomatic. They are composed of inflammatory cells and fibrotic tissue in various proportions. Old nodules may caseate or calcify.

Patients may have enlargement of inguinal, femoral, or other lymph nodes. Localized swelling of the genitalia and inguinal hernias can develop.

Skin disease

Onchocercal dermatitis is caused by the microfilarial stage of the parasite. Intense pruritus may be the only symptom in lightly infected people.

Skin lesions usually consist of a nondescript maculopapular rash with secondary excoriations, scaling ulcerations and lichenification, and mild to moderate lymphadenopathy. Other skin abnormalities can include premature wrinkling, atrophy, patchy hypopigmentation, and loss of elasticity. In severe cases, patients may develop folds of atrophic skin in the lower abdomen and upper medial thighs (“hanging groin”).

Onchocercal dermatitis is generalized in most patients, but a localized and sharply delineated form of eczematous dermatitis with hyperkeratosis, scaling, and pigment changes (Sowdah) is common in Yemen and Sudan.

Eye disease

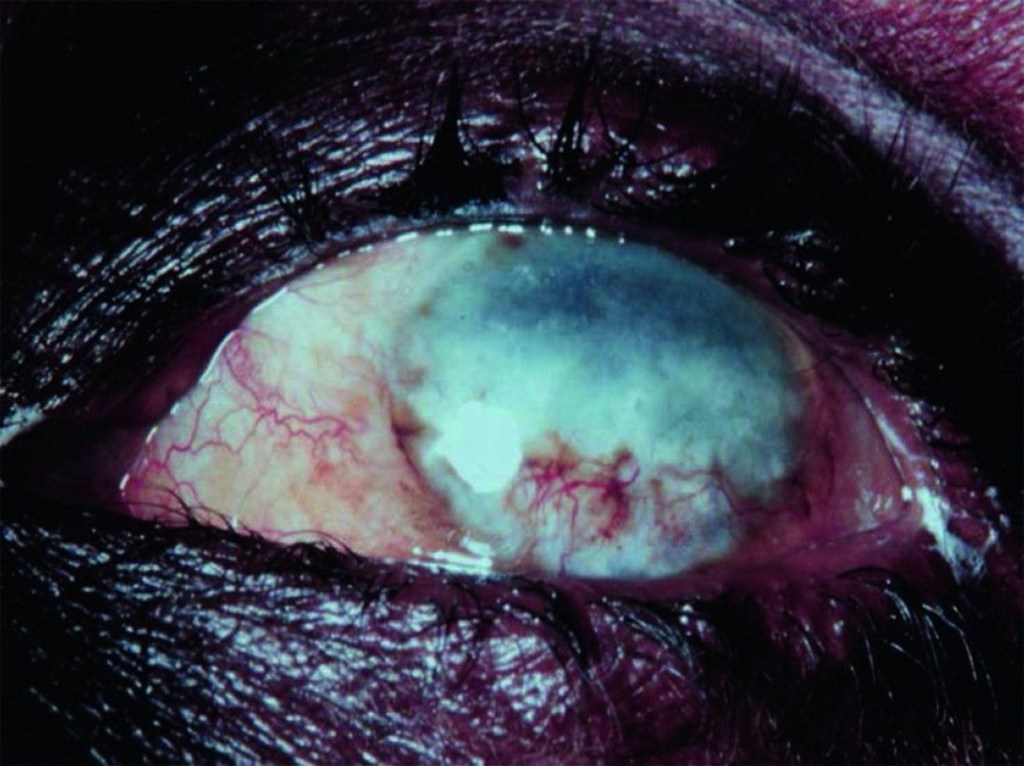

Ocular involvement ranges from mild visual impairment to complete blindness. Lesions of the anterior portion of the eye include

- Punctate (snowflake) keratitis (an acute inflammatory infiltrate surrounding dying microfilariae that resolves without causing permanent damage)

- Sclerosing keratitis (an ingrowth of fibrovascular scar tissue that may cause subluxation of the lens and blindness)

- Anterior uveitis or iridocyclitis (which may deform the pupil)

Chorioretinitis, optic neuritis, and optic atrophy may also occur.

Diagnosis of Onchocerciasis

- Microscopic examination of skin snips or biopsies

- Slit-lamp examination of the cornea and anterior chamber of the eye

Demonstration of microfilariae in skin snips or biopsies is the traditional diagnostic method for onchocerciasis; multiple samples are usually taken (see table Collecting and Handling Specimens for Microscopic Diagnosis of Parasitic Infections). PCR-based methods to detect parasite DNA in skin samples are more sensitive than standard techniques but are available only in research settings.

Microfilariae may also be visible in the cornea and anterior chamber of the eye during slit-lamp examination.

Antibody detection is of limited value; there is substantial antigenic cross-reactivity among O. volvulus and other filaria and different helminths, and a positive serologic test does not distinguish between past and current infection.

Palpable nodules (or deep nodules detected by ultrasound or MRI) can be excised and examined for adult worms, but this procedure is rarely necessary.

Treatment of Onchocerciasis

- Ivermectin

Ivermectin, the primary therapeutic option, reduces microfilariae in the skin and eyes and decreases production of microfilariae for many months. It does not kill adult female worms, but cumulative doses decrease their fertility. Ivermectin is given as a single oral dose of 150 mcg/kg, repeated at 6- to 12-month intervals. The optimal duration of therapy is uncertain. Although treatment could theoretically be continued for the life span of female worms (10 to 14 years), it is usually stopped after several years if pruritis has resolved and no evidence of microfilariae is detected by skin biopsy or eye examination.

Adverse effects of ivermectin are qualitatively similar to those of diethylcarbamazine (DEC) but are much less common and less severe. DEC is not used for onchocerciasis because it can cause a severe hypersensitivity (Mazzotti) reaction to released filarial antigens, which can further damage skin and eyes and lead to cardiovascular collapse. Mild Mazzotti reactions are a frequent complication during treatment, and severe reactions can be managed with low-dose corticosteroids rapidly tapered (1).

Before treatment with ivermectin, patients should be assessed for coinfection with Loa loa, another filarial parasite, if they have been in areas of central Africa where both parasites are transmitted because ivermectin can cause severe reactions in patients with heavy Loa loa coinfection.

Sources & Credit: