A perfect example of cannibalism gone wrong…

“I was still very young when I saw [kuru] and even after we treated it there was no help. Everyone was falling apart. [Kuru victims] were aware there was no cure and that they would die. It wasn’t just one person that this sickness came to—there were about three in a house line and then after they died there would be another three. It was… ongoing… there were many deaths. Once a [person]… was affected by kuru [their] family would think that the clan had poisoned [them] and they would start… shooting at each other and that made it worse. It was chaos!” ~Taurubi

The definition of kuru as both neurodegenerative (not inflammatory) and infectious led to subsequent transmission of Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (CJD) and suggested that kuru represents a novel class of diseases caused by a novel class of pathogens called prions. Kuru won a Nobel prize for Gajdusek in 1976 and, indirectly, as he discovered “prions”, for Stanley B. Prusiner in 1997. Kuru was linked, also indirectly, to a third Nobel Prize for Kurt Wüthrich, who determined the structure of the prion protein.

Introduction & History

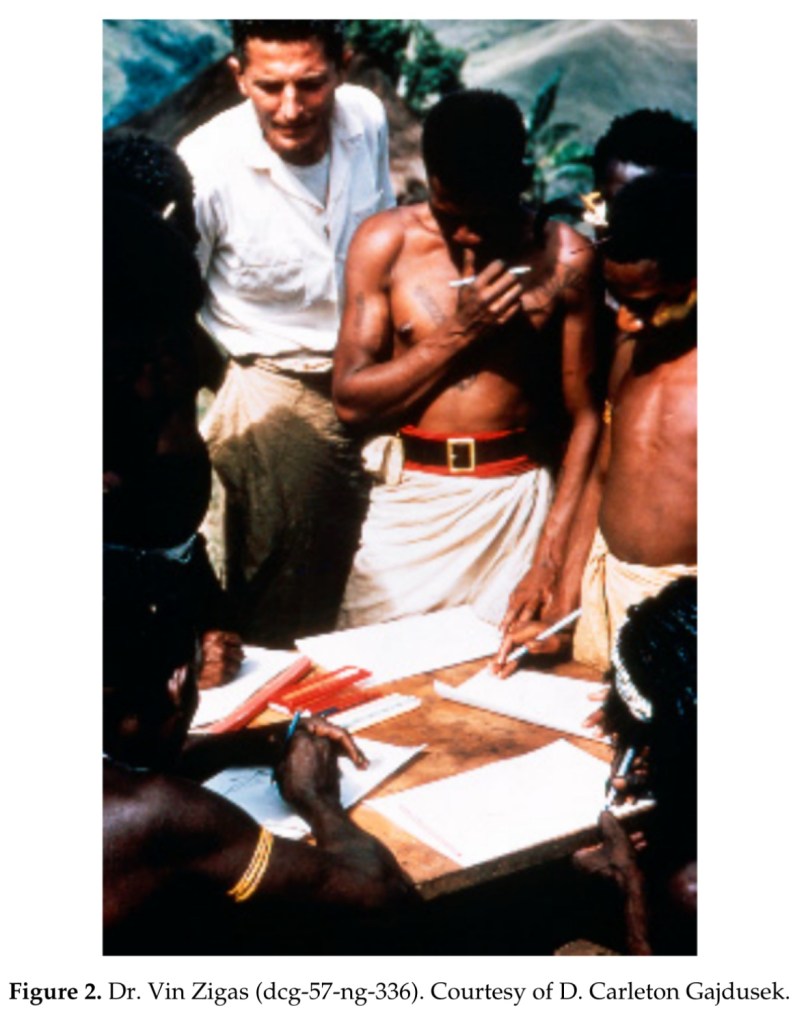

“Kuru”, is the first prion disease that was discovered by D. Carleton Gajdusek (Figure 1). It was also the first human prion disease transmitted to chimpanzees and was classified as “a transmissible spongiform encephalopathy” (TSE), or slow unconventional virus disease. It was first reported in two publications by Gajdusek and Vincent Zigas in 1957 (Figure 2).

“Kuru”, in the Fore language, means to tremble from fever or cold.

The disease was confined to natives of the Fore linguistic group in Papua New Guinea’s Eastern Highlands and neighboring linguistic groups (Auiana, Awa, Usurufa, Kanite, Keiagana, late, Kamano, and Gimi). The Fore reports suggested that kuru first appeared at Uwami, a Keiagana village to the northwest, around 1900, and then in the North Fore around 1920. It then traveled down the southeastern border, arriving at Wanitabe in the central South Fore by 1930. From Wanikanto, where it appeared in 1927, it turned toward the northwest, to Miarasa and Paigata. The first cases at Purosa, six miles south of Wanitabe, appeared in the 1930s.

Kuru became endemic in all villages which it entered and became hyperendemic in the South Fore region. When kuru first appeared, the symptoms were thought to resemble the quills of the cassowary, which also reminded them of the swaying fronds of the casuarina tree, so they fed the victims casuarina bark, a homeopathic treatment that gave little relief. Many people also called the disease “negi nagi”, a Fore term meaning silly or foolish person, because the afflicted women laughed immoderately. In those early days, they joked and took sexual levities with the sick women, as they did with those who had temporary mental derangement. When it became apparent that the victims were all dying, they were forced to co-include that sorcerers were at work.

Endocannibalism (the eating of relatives) was a component of South Fore mourning rituals, in contrast to exocannibalism (the eating of enemies), which was practiced in the north, the difference having consequences for the transmission of the disease. By the 1950s, cannibalism ceased in the North Fore, but was still practiced surreptitiously in the south, where the South Fore said that they continued to hide and eat deceased kin throughout the 1950s.

When a body was considered for human consumption, none of it was discarded, except the gall bladder, which was considered too bitter. In the deceased person’s old sugarcane garden, maternal kin dismembered the corpse. They first removed the hands and feet, then cut open the arms and legs to strip the muscles. Opening the chest and belly they avoided the gall bladder. They next severed the head, fracturing the skull to remove the brain. Meat, viscera, and brain were all eaten. Marrow was sucked from cracked bones, and sometimes the pulverized bones were cooked and eaten with green vegetables.

Although, on epidemiological grounds, the etiology of kuru was thought to be infectious, patients had no meningoencephalitic signs or symptoms (fever, confusion, convulsions, or coma), no cerebrospinal fluid pleocytosis or elevated protein level, and, on autopsy, no perivascular cuffings or other signs of inflammatory brain pathology. Neither the environmental nor then available genetic studies provided any clues. Moreover, all attempts to transmit kuru to laboratory rodents or to isolate any microorganism including a virus, using tissue cultures or embryonated hen’s eggs, were unsuccessful. In other wide-ranging investigations, neither exhaustive genetic analyses nor the search for nutritional deficiencies or environmental toxins resulted in a tenable hypothesis.

On 21 July 1959, Gajdusek, who was at that time in New Guinea, received a letter from the American veterinary pathologist, William Hadlow, at the Rocky Mountain Laboratory in Hamilton, Montana, which stressed the similarities between kuru and scrapie, a slow neurodegenerative disease of sheep and goats known to be endemic in the United Kingdom since the 18th century and experimentally transmitted in 1936. Having seen photographs of kuru plaques at the Welcome Medical Museum exhibition in London, he enclosed a copy of a letter pointing out the similarity of plaques of kuru and scrapie to the editor of Lancet.

“I’ve been impressed with the overall resemblance of kuru, and an obscure degenerative disorder of sheep called scrapie… The lesions in the goat seem to be remarkably like those described for kuru.. All this suggests to me that an experimental approach similar to that adopted for scrapie might prove to be extremely fruitful in the case of kuru… because I’ve been greatly impressed by the intriguing implication, I’ve submitted a letter to The Lancet”.

Kuru incidence increased in the 1940s and 1950s to approach the mortality rate in some villages 35/1000 among a population of some 12,000 Fore people. This mortality rate distorted certain populational parameters; in the South Fore, the female-male ratio was 1:1.67 in contrast to the 1:1 ratio in unaffected Kamano people. This ratio increased to 1:2 and even to 1:3 in the South Fore. Gajdusek even calculated the deficit of women in the population to be 1676 persons. The almost total absence of kuru cases in South Fore among children born after 1954 and the rising of age of kuru cases year by year suggested that transmission of kuru to children stopped in the 1950s when cannibalism ceased to be practiced among the Fore people. Also, brothers with kuru tended to die at the same age which suggested that they were infected at similar age but not at a similar time. The assumption that affected brothers were infected with kuru at the same age led to a calculation of minimal age of exposure for males to be in a range of 1-6 years with a mean incubation period of 3-6 years and the maximum incubation period of 10-14 years.

Alpers and Gajdusek wrote a year before the transmission of kuru was published: “The still baffling, unresolved problem of the etiology of kuru in the New Guinea Highlands has caused as to wonder whether or not any or many of the unusual features of its epidemiological pattern and its clinical course may not be changing with time, or even altering drastically under the impact of extensive rapid cultural change, the result of ever increasing inroads of civilization upon the culture of the Fore people”. The comparison of number of deaths from kuru in the period 1961-1963 and 1957-1959 showed a total 23% reduction, while, among the children, a 57% drop, while the kuru mortality rates decreased from 7.64 to 5.58 deaths per thousand. These alterations were not uniform; the North Fore reduction exceeded the South Fore reduction and it is worthy to recall that the South Fore kuru deaths accounted for the 60% of the total. This trend tended to be observed until the disappearance of the kuru epidemic.

The transmission of kuru to chimpanzee won a Nobel Prize for Gajdusek in 1976.

The list of non-human primates includes rhesus monkeys, marmosets, gibbon and sooty mangabey monkeys. The detailed description of experimental kuru in 41 chimpanzees was published in 1973.

Clinical Manifestations

Kuru is an always fatal cerebellar ataxia accompanied by tremor, choreiform, and athetoid movements (Figure 8).

Kuru is divided into three clinical stages: ambulant, sedentary, and terminal (the Pidgin expressions, wokabaut yet, i.e., “is still walking”; sindaun pinis, i.e., “is able only to sit”; and slip pinis, i.e., “is unable to sit up”). The duration of kuru, as measured from the onset of prodromal signs and symptoms until death was about 12 months (3-23 months).

There is an ill-defined prodromal period (kuru laik i-kamp nau—i.e., “kuru is about to begin”) characterized by headache and limb pains, often in the joints; frequently, knees and ankles came first, followed by elbows and wrists; sometimes, interphalangeal joints were initially affected, along with abdominal pains and loss of weight. The prodromal period lasted several months. Fever and typical signs of infectious disease were not observed, but the patient’s general feeling resembled that of acute respiratory infection. Some patients used to say that they awaited cough; when cough did not come, they awaited approaching kuru.

The prodromal period is followed by the “ambulant stage”, which ends when the patient is unable to move without support of a “family”, which also initiated the search for a sorcerer: This ambulant stage is characterized by the beginning of subtle signs of gait unsteadiness that are noticed first by the patient. Those symptoms, in about a month, advanced to marked astasia and ataxia and incoordination of the muscles in the trunk and lower limbs. As patients knew that kuru means death in about a year, they became withdrawn and quiet. A delicate “shivering” tremor, starting in the trunk, amplified by cold and associated with a “goose flesh”, is followed by titubation and other types of abnormal movements, such as clawing of the toes and curling of the feet. Plantar reflex is always flexor while clonus, especially ankle clonus, is typical, but observed only temporarily.

In the early stages, ataxia could be demonstrated only when the patient stood on one leg; the Romberg sign was almost always negative (two of 34 kuru cases in Alpers’ series); however, with the progression of disease, ataxia became marked and the Romberg sign became positive. Ataxia in the upper limbs followed that in the lower limbs; dysmetria was often the initial sign. Dysarthria appeared early. Involuntary spontaneous and action jerks are a typical sign of kuru. According to Alpers “[it is] difficult to describe and analyze. It appears to include the following components: a shivering component, an ataxic component, and, in the latter stages and certain cases only, the extrapyramidal component. A fine shivering-like tremor may be present from the onset of disease … it is potentiated by cold and thus may not be found in the heat of the day; a sudden drop in temperature not sufficient to make others shiver will induce it in kuru patients. As ataxia increases a more obvious ataxic component is added and the shaking movements become wilder and more grotesque”. The major component in kuru is the intention (cerebellar tremor) and jerky movements or jerks (originally described as tremor or shivering) occurring at rest, when maintaining posture, triggered by movement or other stimuli (lights, noise, or touch). It subsides; “It often seemed to be triggered by minor movement, an adjustment of posture, stretching out the arm in greeting, or even a sudden turning of the eyes”. Patients learn how to control tremor. A child trembling violently, described by Zigas and Gajdusek, found that he may almost completely abolish the tremor when curled into a flexed, fetal position in his mother’s lap. A horizontal convergent strabismus is a typical sign, especially in younger patients; nystagmus was common but the papillary responses were preserved. Facial hemispasm and supranuclear facial palsies of different kinds were also observed.

The second “sedentary” stage begins when the patient is unable to walk without constant support and ends when he or she is unable to sit without it. “The gait was, by definition non-existent. However, if a patient was ‘walked’ between two assistants a caricature of walking was produced, with marked truncal instability, weakness at hips and knees and heavy leaning on one or other assistant for support; but steps could be taken, and were characterized by jerky flinging, at times decomposed movements, which led to a high-steppage, stamping gait”. Postural instability, severe ataxia, tremor, and dysarthria progress endlessly through this stage. Deep reflexes may be increased, but the plantar reflex is still flexor. Jerky ocular movements: were characteristic. Opsoclonus, a rapid horizontal ocular agitation was also occasionally noticed. Zigas and Gajdusek reported peculiar, jerking, clonic movements of the eyelids and eyebrows in patients confined to the dark indoors of huts and then transported outdoors to the light. Two cases of 34 showed signs of dystonia.

In the third stage, the patient is bedridden and incontinent, with dysphasia and primitive reflexes, and eventually succumbs in a state of advanced starvation. “The patient at the beginning of the third stage usually spent the day supported in the arms of a close relative”. Extraocular movements were jerky or slow and rigid. Deep reflexes were exaggerated, but Babinski signs were never observed. Generalised muscle wasting became seen and fasciculation, spontaneous or evoked by tapping, was observed. Some symptoms of dementia were also noticed, but in terminal stages, patients many understood the Fore language and tried to answer appropriately. A strong grasp reflex occurred, as well as fixed dystonic postures, athetosis, and chorea. In one case “almost constant small involuntary movements, involving mouth, face, neck, and hands” were seen.

Terminally, “the patient lies moribund inside her hut surrounded by a constant group of attending relatives… She barely moves and is weak and wasted. Her pressure sores may have spread widely to become huge rotting ulcers which attract a swarm of flies. She is unable to speak. The jaws are clenched and have to be forced open in order to put food or fluid in. Despite her mute and immobile state, she can make clear signs of recognition with her eyes and may even attempt to smile”. It is worth mentioning incredible support given by Fore to dying kinsmen. “The family members live with the dying patient, siblings sleep closely huddled to their brother or sister in decubitus, parents sleep with their Kuru-incapacitated child cuddled to them and a husband will patiently lie beside his terminal, uncommunicative, incontinent, foul smelling wife”.

Neuropathology

The first examination of kuru neuropathology (12 cases) was published by Klatzo et al. in 1959.

•Neurons were shrunken and hyperchromatic or pale, with dispersion of Nissl substance with intractoplasmic vacuoles similar to those already described in scrapie.

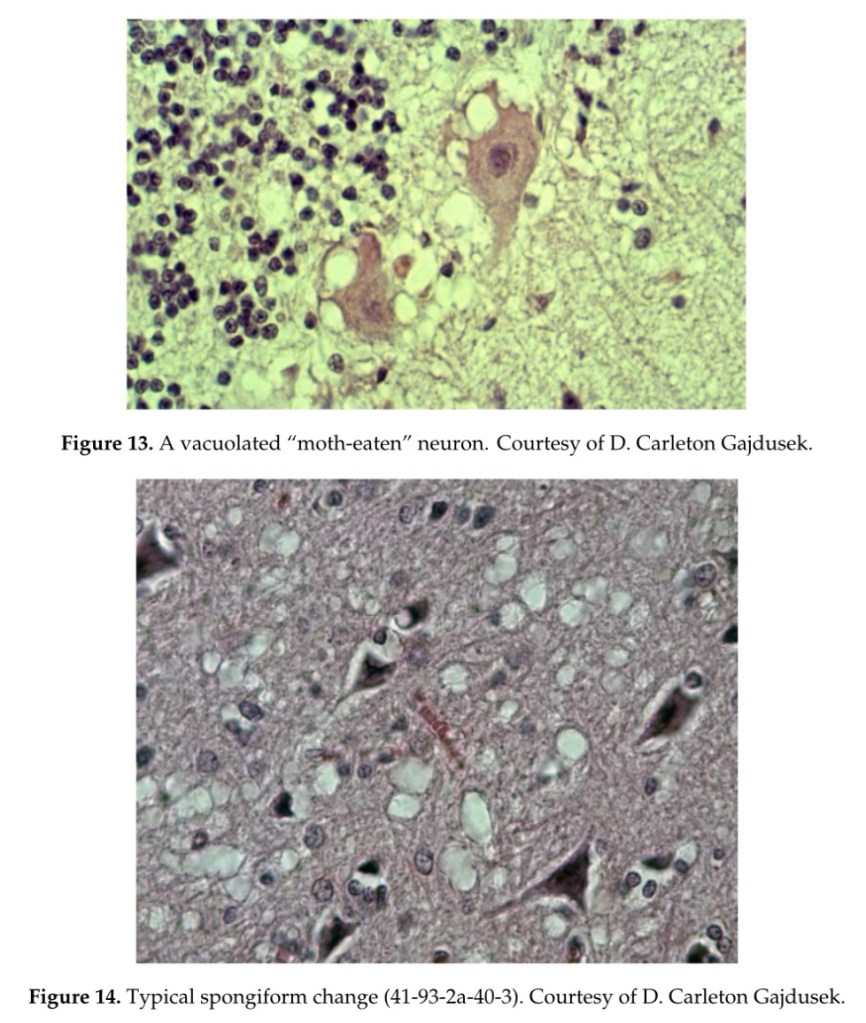

•In the striatum, some neurons, as well as Purkinje cells in the cerebellum, were vacuolated to such a degree that they looked “moth-eaten” (Figure 13). Spongiform change was seen (Figure 14).

•Neuronophagia was observed. A few binucleated neurons were visible, and torpedo formation was noticed in the Purkinje cell layer, along with empty baskets that marked the presence of absent Purkinje cells.

•In the medulla, neurons of the vestibular nuclei and the lateral cuneatus were frequently affected; the spinal nucleus of the trigeminal nerve and nuclei of VIth, VIIth, and motor nucleus of the VIth cranial nerves were affected less frequently, while nuclei of the XIIth cranial nerve, the dorsal nucleus of Xth cranial nerve, and nucleus ambiguous were relatively spared. In the cerebral cortex, the deeper layers were affected more than the superficial layers, and neurons in the hippocampal formation were normal.

•In the cerebellum, the paleocerebellar structure (vermis and flocculo-nodular lobe) was most severely affected, and spinal cord pathology was most severe in the corticospinal and spinocerebellar tracts.

•Astroglial (Figure 15a,b) and microglial proliferation was widespread; the latter formed rosettes and appeared as rod or amoeboid types or as macrophages (gitter cells).

•Myelin degradation was observed in 10 of 12 cases.

•Interestingly, the significance of vacuolar changes was not appreciated by Klatzo et al., but “small spongy spaces” were noted in seven of 13 cases studied by Beck and Daniel.

The Fore believed that kuru was the result of sorcery carried out by an envious opponent. A would-be sorcerer, living nearby, could gain a part of the victim’s body-nail clippings, hair, feces, saliva, or partially consumed food such as the discarded skin of sweet potato or even a piece of clothing. These items were enclosed in leaves and bindings made into a “kuru bundle” which was placed in swampy ground. As the bundle disintegrated, the characteristic kuru tremor registered in the victim’s body.

Divination rituals were sometimes enacted to identify a sorcerer: If a suspect approached the corpse and it emitted body fluids (which sometimes happens after death), the guilty person was found. Another divination method was to place hair clippings from a kuru victim into a bamboo cylinder, and a freshly killed possum in another, then calling the name of a suspected sorcerer. If the possum meat remained uncooked, it was thought that the sorcerer’s location was identified. Divination rituals in general identified places of residence, rather than the specific names of individual men.

The discovery of kuru opened new vistas of human medicine and was pivotal in the subsequent transmission of Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease, as well as the relevance that bovine spongiform encephalopathy had for transmission to humans. The transmission of kuru was one of the greatest contributions to biomedical sciences of the 20th century.

Kuru, an extinct exotic disease of a cannibalistic tribe in a remote Papua New Guinea, still impacts on many aspects of neurodegeneration research. It is, thus, rather curious that, in the newest Handbook of Clinical Neurology, there is no kuru chapter, with just a small note on history.

Originally published on 7th March 2019 in the MDPI Viruses Journal.

Source: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/331613629_Kuru_the_First_Human_Prion_Disease