The Knights of Saint John

“Then in Palestine,

By the wayside, in sober grandeur stood A Hospital that, night and day, received The pilgrims of the west, and, when ’twas asked,

” Who are the noble founders?’ every tongue At once replied, ‘The merchants of Amalf”;

That Hospital, when Godfrey sealed the walls, Sent forth its holy men in complete steel, And hence, the cowl relinquished for the helm, That chosen band, valiant, invincible,

So long renowned as Champions of the Cross In Rhodes, in Malta.”

Samuel Rogers-Italy, Amalf.

The Knights of Saint John, founded after the conquest of Jerusalem (1099), were renowned in Europe as Christian soldiers. They were, however, equally famous for their charities, especially for their great Hospital in Jerusalem.

Bull of Pope Paschal II, February 15, 1113, confirming the foundation of the Order of Saint John of Jerusalem.

(In the Palace Armory, Valletta, Malta)

Before 800 Latin documents used the Greek word xenodochium to describe houses of public charity. Thereafter, the Latin word hospital was common, though writers still frequently employed the Greek term. Both xenodochium and hospital refer to travelers’ inns. Since wayfarers often fell ill on their journeys both because of the hardships of medieval travel and because of the new diseases encountered from place to place, inns had to provide care for the ill. Some of these inns, as we shall see, evolved into houses only for the sick, while others remained simple hospices with some casual care for travelers stricken by disease, but the terms hospital and xenodochium were used for both institutions.® Though the Greek East developed a distinctive word, nosokomeion, for hospitals dedicated to the sick, the Latin West continued to use the more general terms.

The Latin documents from the Merovingian and Carolingian periods frequently mention hospices. These were often built next to monasteries or in the surviving Roman towns of Italy and southern Gaul. Upon closer examination, however, very few of these xenodochia seem to have operated as true hospitals. Though the hospice founded by King Childebert in Laon during the sixth century was designed to serve pilgrims and to provide care (cura) for the sick, there is no reference to a disciplined regimen for the patients, to hospital wards, or to the activities of a physician.

A Knight Hospitaller in armor with the tunic of the Order over his breastplate.

Pinturicchio’s portrait of Alberto Aringhieri.

Chapel of St. John in the

Cathedral of Siena.

The Muristan is the name now given to the ancient convent of the Knights Hospitalliers, the original home of the Order in Jerusalem. It lies south of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, and measures 170 by 150 yards. There were originally many buildings, among them the ancient Church of Saint John Eleemon, which became the church and hospital of the Knights Hospitallers, and presumably was then rededicated to Saint John the Baptist. When Saladin took the Holy City in 1187 he converted the whole site to the endowment of the Mosque of Omar. It was his nephew who in 1216 instituted a lunatic asylum in what had been the conventual church. The term Muristan, which connotes a lunatic asylum, was given to the whole area.

The Blessed Gerard.

Founder and Rector of the Order of the Hospitallers of Saint John of Jerusalem.

(From Abbé Vertôt’s History of the Knights of St. John.)

The old Latin name of the order of which we treat, was Ordo Equitum Hospitaliorum Sancti lohannis Hierosolymitani, known officially as The Sovereign Military Order of Saint John of Jerusalem called of Malta. Its members have been known, on account of their territorial sovereignty, first as the Knights of Rhodes, and later as the Knights of Malta.

A study of the medical and charitable work Hospitalitas, as it was called, of the Order of the Hospital or the Knights of Saint John, may, following their political vicissitudes, be divided into three divisions of unequal length:

I From the foundation of the Order in the latter half of th eleventh century, to the occupation of the island of Malt: in 1530

Il The occupation of Malta (1530-1798)

III From the loss of the island of Malta to the present (1798-1938)

The purpose of the order from its inception was the care of the needy sick. At first there was no thought of its becoming military in character. However one of the duties in the care of the sick is their protection from enemies, and the Knights early found it necessary to defend their hospitals against the enemies of their Faith. They were the first organized military medical officers, and then as now, bore their full share of danger on the field of battle. Not ” non-combatants” they, but warring physicians who could strike the enemy mighty blows, and yet later bind up the wounds of that same enemy along with those of their own comrades. Thus they grew into a military order, taking vows of poverty, chastity and obedience, and obligating themselves to the service of needy sick folk, at the same time fighting the enemies of Christianity. This was a union of religion with medicine.

Description of the Hospital of the Order at Jerusalem

John of Würzburg, a German pilgrim who visited Jerusalem about the year 1160, has left us an interesting reference. Just who John was is not known, other than that he was a priest of the church of Würzburg. His Latin text was translated into English by Aubrey Stewart of Trinity College, Cambridge, in 1896. The following is a passage:

The City of Jerusalem.

(From Baudoin’s Histoire de Malthe)

The Hospital founded by the Knights of Saint John in Jerusalem has given the Order the name by which it is best known-Knights Hospitallers.

“Over against the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, on the opposite side of the way towards the south, is a beautiful church built in honor of John the Baptist, annexed to which is a hospital, wherein in various rooms is collected together an enormous multitude of sick people, both men and women, who are tended and restored to health daily at very great expense. When I was there I learned that the whole number of these sick people amounted to two thousand, of whom sometimes in the course of one day and one night more than fifty are carried out dead, while many other fresh ones keep continually arriving. What more can I say?”

In another paragraph John of Würzburg tells of the palace of the Knights Templar, and of the extensive revenues that their house received. He adds: “It gives considerable amount of alms to the poor in Christ, but not a tenth part of that which is done by the Hospitallers” (ibid., p. 21).

Rabbi Benjamin “son of Jonah, of blessed memory, of Tudela, in the kingdom of Navarre” was an extensive traveler. Between the years 1160 and 1173 he visited Palestine and elsewhere in the Near East. He was in Jerusalem in 1163 and wrote on his return:

There are in Jerusalem two hospitals, which support four hundred knights, and afford shelter to the sick; these are provided with everything they may want, both during life and death; the second is called the hospital of Solomon, being the place originally built by King Solomon. This hospital also harbors and furnishes four hundred knights, who are ever ready to wage war, over and above those knights who arrive from the country of the Franks and other parts of Christendom.These generally have taken a vow upon them-selves to stay a year or two, and they remain until the period of their vow has expired.

(Thomas Wright, Early Travels in Palestine, London, 1848, p. 83.)

Sir John Maundeville, in describing Mount Sion, tells of Aceldama where there were many tombs of Christians.

“A hundred paces to the east is the charnel-house of the hospital of St. John, where they used to put the bones of the dead men” (ibid., p. 175).

Great Seal of the Hospital of Saint John of Jerusalem.

This is the reverse of the Bulla of the Master of the Hospital.

This design was used by one head of the

Order after another.

The figure may represent a

patient in the Hospital at Jerusalem.

The ancient seal of the Hospital in Jerusalem gives, says Biasiotti, an idea of the appearance of the Church. On the seal we see the figure of a patient lying on a. bed, facing to one side, and in the background a cupola from which is suspended a lamp. A censer hangs near the feet, while at the patient’s head is the cross of the Order. He adds that the design may also represent a funeral within the chapel, and this thought is borne out by the records. The design described is that of the reverse of the Great Seal or the Master’s Bulla.

In 1341 the Hospital was still used for the care of the sick and wounded, so the work of the Knights may be said to have continued long after they had been driven from the Holy City. A German pilgrim, Ludolph von Suchem, who was in Palestine from 1336 to 1341, includes the following in his description of Jerusalem:

“Near the Church of the Holy Sepulchre once dwelt the brethren of Saint John of Jerusalem, and their palace is now the common hospital for pilgrims. This hospital is so great that 1000 men can easily live therein, and can have everything that they want there by paying for it. It is the custom in this palace or hospital that every pilgrim should pay two Venetian pennies for the use of the hospital. If he sojourn there for a year he pays no more, if he abide but one day he pays no less.”

(Palestine Pilgrims’ l’ext Soc., Vol. XII, pp. 106-7.)

King Andrew II of Hungary, who visited the Holy Land during the occupation of Acre by the Hospitallers, proved one of the Order’s most generous benefactors. He admired their Grand Master, Garin de Montaigu, from the moment he first knew him in Cyprus. During the King’s residence in Acre he lived, not at the royal palace as one might suppose, but in the Convent of the Hospitallers, where he was deeply impressed by their work of mercy. During the great raid across the River Jordan, in which he took part, he likewise had occasion to see their gallantry in action. Upon his own request he was affiliated with the Order as a Confrater, sharing in its spiritual privileges.

On his return he told of the enormous number of poor people who were fed by the Knights each day, of sufferers who were given beds and treated, and that those who died received Christian burial (Raynaldi, Annales Eccles., I, 436). The King a little later granted the Order the sum of 500 marks of silver (a mark weighed eight ounces) each year, secured upon the royal salt-works at Szalacs.

When the King visited the Knights’ castles of Margat and Le Crac, he made a further donation, likewise secured upon the salt-works of Szalacs, of 100 marks of silver a year to each fortress, to be used in strengthening the defenses.

Saladin’s Secret Visit to the Hospital at Acre

One of the oldest legends of the Knights of Saint John is that of the visit paid their hospital in Acre by the Sultan of Egypt, the chivalrous Saladin. The story has often been told in song and verse. Saladin is said to have come to the hospital disguised as a sick beggar, and seeking succor.

Since that privilege was never denied anyone, Christian or not, he was admitted at once. Perhaps he was the first of the Seigneurs Malades, of whom we will hear presently.

He was offered treatment, but sadly told the warder that he knew— as do the afflicted in so many ancient stories—that but one thing would restore his health. He was promised it unconditionally, if available. But what was the horror of the Knight when the supposed beggar said that he must be given the heart of Moriel, the noble steed of the Master himself, and that to eat this precious morsel would speedily restore him to health and strength.

Other remedies were offered in vain; the unknown patient would have none of them.

The Master was notified of the sacrifice demanded of him and, true to the principles of the Hospitallers, gave the order that Moriel must die that a human life might be saved. The Sultan was satisfied that what he had heard of the Knights’ willingness to sacrifice all for their charges was true, and Moriel was spared.

Saladin asked that he be left alone with the Master, and to him revealed himself.

“Know, O Master of the Knights Hospitallers, that I am none other than Saladin. We stand here alone, face to face. I am unarmed and at your mercy. But I know that I am in no danger. Men, even though Christians and Unbelievers, who can care for the sick and wounded so tenderly do not have as their leader one who could harm a guest within their gates. I shall know how to respect your Order thenceforth.”

And he departed in peace. There are numerous variants of the story, but the thought in them all is that Saladin at first hand tested the spirit of charity of the Hospital-lers and it was not found wanting.

When the great Saracen returned to his own country, he sent to the brethren of the Hospital a charter, sealed with his own seal, which is said to have read:

“Let all men know that I, Saladin, Soldan of Babylon, give and bequeath to the Hospital of Acre a thousand besants of gold, to be paid every year in peace or war, unto the Grand Master be he who he may, in gratitude for the wonderful charity of himself and his order.”

(E. J. King, Knights Hospitallers in the Holy Land, p. 157.)

There may be some foundation for this story after all, for during the Saracen occupation of Acre after the battle of Hattin or Tiberias (1187), Saladin took for his own use the house of the Templars, formerly the palace of the Egyptian governors, and gave the house of the Hospitallers to the Moslem clergy, turning the bishop’s palace into a hospital.

AD 1181

The Chapter-General of 1181 under Fr. Roger des Moulins, Master of the Hospital, adopted the following statutes, approved by Pope Lucius:

And secondly, it is decreed with the assent of the brethren, that for the sick in the Hospital of Jerusalem there should be engaged four wise doctors, who are qualified to examine urine, and to diagnose different diseases, and are able to administer appropriate medicines.

And thirdly, it is added that the beds of the sick should be made as long and as broad as is most convenient for repose, and that each bed should be covered with its own coverlet (covertour) and each bed should have its own special sheets.

After these needs is decreed the fourth command, that each of the sick should have a cloak of sheepskin (pelice a vestir), and boots for going to and coming from the latrines, and caps of wool. Of whom the Bailiff of Antioch should send to Jerusalem two thousand ells of cotton cloth (toile de coton) for the coverlets of the sick. The Prior of Mont Pelerin [i.e. Tripolis] should send to Jerusalem two quintals (i.e. 200 pounds) of sugar for the syrups, and the medicines and the electuaries [medicinal powders made up with honey or sugar] of the sick. For this same service the Bailiff of Tabarie (Tiberias) should send there the same quantity. The Prior of Constantinople should send for the sick two hundred felts.

AD 1262

At the Chapter-General of 1262 under Master Hugh Revel, ” a man remarkable for the soundness of his judgment,” says the

Chronicle, ” and he placed the affairs of the House on a sound basis,” the following statutes, inter alia, were approved :

33. Item, it is decreed that the Brother of the Infirmary [i.e. the Infer-marian] every night after Compline [the last Hour of the day, at seven o’clock in winter, and at eight o’clock in summer] and after Matins, should visit the beds of the sick brethren who lie in the infirmary.

And that no

Caravanier [i.e. those brothers on duty with the Caravans, as the military expeditions were called] nor other serjeant [lay brother] nor Donat [lay-man attached to the Order] should give to the sick brother the money (derniers), that it is customary to give [i.e. the usual pocket-money given the brothers for their charities], but the brother himself [i.e. of the In-firmary]. And at all times at which the doctor shall visit the sick brethren, the brother of the Infirmary should go with him, that is to say in the morning and in the evening. . . .

AD 1304

The Chapter-General of 1304, likewise held under the rule of Fr.

William de Villaret, Master of the Hospital, enacted the following statutes, among others:

4. Concerning Brethren who shall be in the Palais des Malades and are under the Orders of the Hospitaller.

Item, it is decreed that the brethren, who shall be in the Palais des Malades, and are under the orders of the Hospitaller, that if God summon them, that all the things which shall be found with them, should come into the hands of the Hospitaller, save money,

which should come to the Treasury, and

save armour and beasts, which should come into the hands of the Marshal, and the personal clothing and the other things, just as decreed above, which should come into the hands of the Drapier; cloth of gold should be for the church, coverlets of silk should be for the Palais des Malades….

11. Concerning the Infirmarian that he be bound each year at the Chapter-General to give an account of the coverlets and of the sheets and of the blankets.

Item, it is decreed that the Infirmarian should be bound each year at the Chapter-General to give in writing the quantity of coverlets and of sheets and of blankets and of mattresses, that he shall have in the Infirmary, and that shall have been added during that year.”

At the end of the thirteenth century there was a code of regulation drawn up by Fr. William de St. Estene, which is known as th Judgments and Customs of the Hospital. The Judgments (Esgarts) were the decisions of the Chapter-General on specific cases, but regarded as applicable to similar cases. The customs (usances) constituted the traditional procedure of the Order. Here follow certain of these Judgments

which concern the brethren as patients in the Order hospitals:

- And if any brother be ill in his bed or in his chamber for three days, and have not the things which are necessary for him, just as was decreed at Margat, whoever shall be to blame, if a complaint about it be lodged before the Grand Bailiff, let him undergo the Septaine [seven days penance]. And afterwards if the Bailiff have commanded to give him what is necessary, and again it be not done, let him undergo the Quarantaine [forty days penance, during which time, as also during the Septaine, the culprit was flogged in church every Wednesday and Friday in the presence of the Convent, i. e. the Headquarters of the Order]. The same also applies in the case of the brother who lies in the Infirmary, just as is said above.If a brother lie in his bed for three days, and afterwards go not to the Infirmary, the In-firmarian is not bound to supply him with anything.

72. If any brother, who has his duty in the Infirmary, do not give to the sick the things that are necessary for them, or if he do not give them to eat before the brethren go to eat, and all things as provided by the House, let him undergo the Septaine. …

78. And if any brother have himself bled without leave, unless it be because of illness, or because the Bailiff be not in the House, or anyone holding his place, let him undergo the Septaine.

Among the Customs (Usances), we find the following :

- Which deals with the sick brethren who are in the Infirmary. In the House of the Hospital it is customary that the sick brethren, who are in the Infirmary, when they desire to go to the baths or to any place of recreation (leuc desdure), should ask leave of the Infirmarian, and with his leave they can rightly go

Organization of the Order

The head of the Order is the Grand Master who is elected for life. By Papal decree he has the rank of Prince, the precedence of a Cardinal and the title Most Eminent Highness. The present Grand Master is Prince Chigi-Albani, the seventy-sixth holder of this exalted office. The Order was originally composed of Knights, Chaplains, and servants. Later there were added persons called Donats, who had made contributions to the Order’s treasury. The heads of the Priories and Commanderies were known respectively as Priors and Commanders. Besides the Priors and Grand Commanders, the order had Piliers, who were in charge of the Auberges of the Order in Rhodes and Malta. These three grades constituted the Grand Dignitaries of the Order. The bailiffs or baillis were in charge of bailwicks or bailliages and had seats in the Chapter-General.

The exact requirements vary in the several langues but all presuppose noble descent. In general, the requirements of the two independent Orders of Saint John (respectively in Germany and in Britain) are similar to those in the Sovereign Order.*

Knights of Justice of the Sovereign Military Order of St. John of Jerusalem (Order of Malta) must be unmarried. Otherwise the requirements for admission to that grade are similar to those for the Knights of Honor and Devotion. For the Langue of Italy the candidate must prove that each of his four grandparents came of a family that has been noble for not less than 200 years. For the Langue of Germany (including Hungary, Austria, etc.) the candidate must show that each of his great-great-grandparents was of noble birth. This is the rule of the “six-teen quarters” so often mentioned in history.

For the British Association the candidate must offer the same proofs as for the Langues of Italy or Germany; or he may prove that his family (male line) was noble, i.e., entitled to arms, as early as 1485, the date of the commencement of the reign of Henry VII of England, which is considered the close of the feudal period. The Langue of Spain and the Portugese Assembly require the candidate to prove that each grandparent was of a family noble for at least a century.

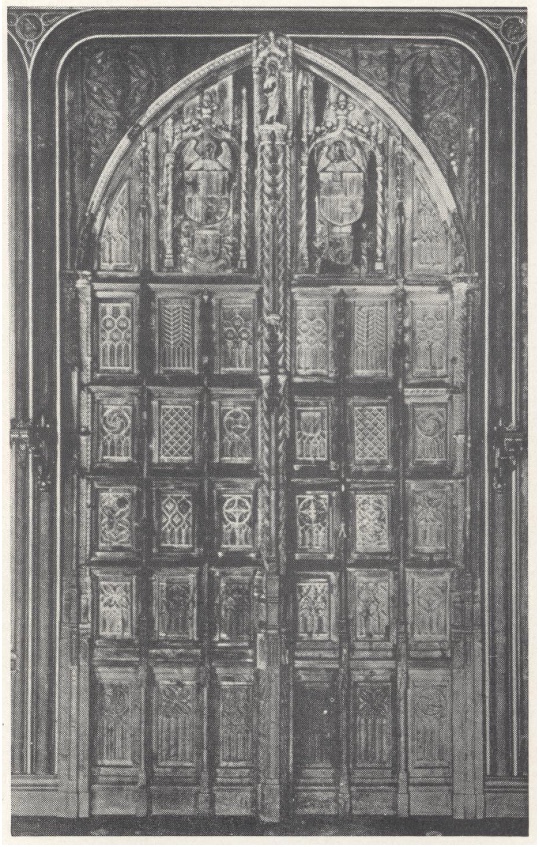

Carved cedar doors from the Hospital of the Knights of

Saint John at Rhodes.

Now in the Salle des Croisades at the Museum of Versailles, to which they were transported in 1836, being a gift to King Louis-Philippe by Sultan Mahmond of Turkey.

Public Health Measures at Rhodes

In Rhodes there were several important sanitary measures intro-duced. Under Grand Master d’Aubusson (1503-1512), among other municipal ordinances, there was one creating a health commission (Domini Sanitatis). It consisted of representatives of the Order and citizens of the town (two Greeks and two Franks), besides the physicians and apothecaries of the Hospital. During the epidemic of plague a strict quarantine was enforced. All persons who had been exposed to the disease were isolated for a period of forty days (hence our term “quarantine”) and if such exposure had been through their fault, a fine of 50 ducats was imposed. If plague were present on ships in the harbor, men were prohibited under pain of death from coming ashore. Less serious violations of the rules were punished by fines. After recovery from or exposure to the disease, visitors were not permitted until permissions of the chief physician was obtained. Apothecaries who sold inferior drugs were subject to fine and imprisonment, and the same applied to careless or unskilled compounding.

It is but just to say that Solyman, like Saladin of old, acted with enlightenment and mercy. He allowed the knights to leave Rhodes quietly and without molestation, and to embark for Christian territory on their own vessels.

Sisters of the Order of Saint John of Jerusalem

The nuns of the Order of Saint John of Jerusalem were established almost as early as were the Knights Hospitallers themselves. At about the time that the hospital for men was constructed, as we have seen, there was erected a hospice for women, known as that of Saint Mary Magdalene. The name of the first abbess was Agnes, and the nuns, like the monks, followed the Rule of Saint Augustine. They wore the eight-pointed cross in white on a red habit. Certain houses of the Order in early days had sisters attached, for the benefit of women patients (Delaville Le Roulx, Les Hospitaliers en Terre Sainte, pp. 299-300).

With the fall of Jerusalem the sisters of the Order were scattered and, it is said, ended their days in peace attached to various com-manderies, as was the custom.

In England Henry II established them in 1186 in the nunnery at Buckland in Somerset a property that they held until Henry VIII dispossessed the Order. Queen Sancha, wife of Alfonso II, King of Aragon, and mother of Peter II, founded a house in 1188 at Sigena, between Lérida and Saragossa, in honor of Our Lady, in which poor ladies of noble families might be received without the requirement of a dot, upon proving their nobility, as was required by the Knights of Saint John of Jerusalem.

After the death of her husband (1196), Queen Sancha and one of her daughters entered the house at Sigena and took the vows, the Queen herself becoming Prioress. So lavish were the gifts of the Queen that the houses were more like a palace than a religious establishment.

The third house for the nuns of the Order of Saint John was established at Pisa in 1200, an establishment rendered famous by the beautiful life of one of its inmates, Saint Ubaldesca, the most beloved of the saints of the Order after the founder himself. She was born in 1136 and even when young performed such acts of mercy that she was already well known when she made her profession in the Order of Saint John. Her tender care of the sick and wounded, and her tireless energy for others, made her considered almost a saint even while yet living. She died in 1206. The Abbé Vertôt, one of the Order’s best known historians, says of her: ” Nature formed her generous and beneficient; grace rendered her charitable; she was the mother of the poor; the sick met with a relief always at hand in her assiduous care; there was no kind of misery but she brought a remedy for it, or gave consolation under it …” (Vertôt, ibid., Liber III).

The sisters of the Order, no less than the Knights, knew how to sacrifice themselves for duty. When the city of Antioch was about to be captured by the Moslem force, the sisters refused to depart but elected to remain behind and care for the sick. They were under no misapprehension as to the fate that would be theirs when captured.

Colonel King recounts the following ghastly story of their martyrdom :

There was in the city [Antioch] a convent of the sisters of the Order, which had recently been established there, about the year 1260. The Mother Superior, when she knew that the city had fallen, called her nuns around her, and warned them what they must expect of the licentious Moslem soldiery. And then, since even under such circumstances suicide was a sin unpardonable, she showed them one way of escape, to render their countenances so horrible and loathsome, that the brutal enemy in disgust would slay them instantly and so send them pure and undefiled to join their Saviour in Paradise. And it is said that these brave sisters of the Order, following the example of their Mother Superior, cut off their noses, and tore their cheeks to ribbons with the points of their scissors, and so, horrible to look upon and covered with blood, awaited the glorious crown of martyrdom which mercifully was long delayed to them.

(E. J. King, The Knights Hospitallers in the Holy Land, p. 264.)

Source:

•MEDICAL WORK OF THE KNIGHTS HOSPITALLERS OF SAINT JOHN OF JERUSALEM*

*Based on lectures delivered before the New York Academy of Medicine, 1930 and the Richmond Academy of Medicine, 1938

EDGAR ERSKINE HUME

Bulletin of the Institute of the History of Medicine, Vol. 6, No. 5 (MAY, 1938), pp. 399-466 (68 pages)

•The Knights of Saint John and the Hospitals of the Latin West

Timothy S. Miller

Speculum, Vol. 53, No. 4 (Oct., 1978), pp. 709-733 (25 pages)