“Mitochondrial disease is different in every individual that I have encountered in my clinical practice of nearly 30 years. Even siblings sharing the same homozygous mutation rarely (I would go so far as to say never) manifest with an identical set of problems and rate of progression. Each has his/her own unique problems and responses to environmental stressors. Whether these are the result of their genetic background or environmental factors (e.g. timing of exposure to first viral infection [140]) is unknown in the majority of cases. But sometimes we are given small clues. I saw two brothers with the same homozygous mutation in a complex III assembly gene but one had worse development, more challenging behaviour, higher blood lactate values and a more severe movement disorder. This brother’s karyotype was 47XXY, whereas his more mildly affected brother had the usual male chromosomal complement of 46XY. However, it would be extremely challenging to prove that the extra X chromosome is indeed the cause of the differing phenotypes in these two siblings. Work on differentiated cells and organoids derived from induced pluripotent stem cells may eventually help to unravel the complex relationship between genotype and phenotype in mitochondrial diseases [141, 142].”

Liz Curtis describes how the loss of Lily drove her to set up a foundation that funded a gene test for the condition.

Mitochondrial disease is a broad term to describe a pathological condition attributed to loss-of-function mutations in mitochondrial proteins encoded by mitochondrial or nuclear genes.

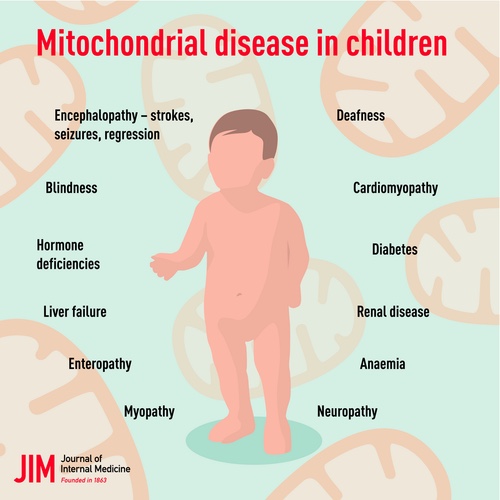

These disorders arise from mutations in either mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) or nuclear DNA (nDNA), both of which encode subunits of OXPHOS as well as structural or functional mitochondrial proteins.3 These proteins are not only integral to classical mitochondrial metabolism—such as OXPHOS, the Krebs cycle, lipid metabolism, and nucleotide metabolism—but also play key roles in mitochondrial quality control, calcium homeostasis, cell death, and inflammation. Deficiencies in these proteins can lead to mitochondrial dysfunction and subsequent energy failure.4 Given mitochondria’s ubiquitous presence and critical role in cellular metabolism, any tissue in the body can be affected.5 However, organs and tissues with high energy demands, such as the brain, nerve, eye, cardiac, and skeletal muscles, are particularly susceptible to energy failure due to OXPHOS defects, with phenotypes often manifesting in neurological, ophthalmological, and cardiological systems.6 The symptoms of mitochondrial diseases are diverse, with developmental delay, seizure (encephalopathy), hypotonia (myopathy), and visual impairment (retinopathy) being prominent indicators.6,7

Despite recent advances, the molecular mechanisms underlying these diseases remain incompletely understood. The extreme phenotypic and genetic heterogeneity of mitochondrial diseases further complicates diagnosis, making misdiagnosis a common issue.8

Mitochondrial diseases have been recognized as pathway-based diseases rather than merely energy-deficit diseases.7 The variable clinical presentations and tissue specificity suggest that there are contributing factors beyond energy deficit during disease development.9 The reduction of ATP produced from OXPHOS can be compensated by enhanced anaerobic glycolysis, and thus mitochondrial genetic defects may not reduce ATP production.10,11 Furthermore, genetic defects are not always sufficient to cause cellular dysfunction as mitochondria can buffer against mitochondrial lesions, making environmental insults sometimes important to trigger these genetic disorders.12 Recently, the mitochondrial stress responses have gained close attention.9

Pro-nuclear Transfer is a technique designed to eliminate the possibility or even reduce further progression of the mitochondrial disease patterns leading to death. A fertilised egg is taken from the affected mother with a faulty mitochondria and a needle removed the egg’s pro-nuclei which contains both genes from mother and father. Then, a fertilised egg is from the healthy donor has its parents’ genetic information removed and replaced with the patient’s. Now, we have an embryo which was from the affected parents with healthy mitochondria. The research was conducted at the Newcastle Fertility Centre, Newcastle Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust. The babies created were four boys and four girls, two of them, identical twins were all born healthy. In three of those babies, some mitochondrial disease was carried over but these levels were too low to cause the disease. There’s a follow up to monitor the progress of the findings.

The field of mitochondrial medicine has made enormous strides in the last 30 years, with approaching 400 different genes across two genomes now linked to primary mitochondrial disease. However, many important questions remain unanswered, including the reasons for tissue specificity and variability of clinical presentation of individuals sharing identical gene defects, and a lack of disease-modifying therapies and biomarkers to monitor disease progression and or response to treatment.

Clinical complexity: Canonical syndromic presentations of childhood mitochondrial disease

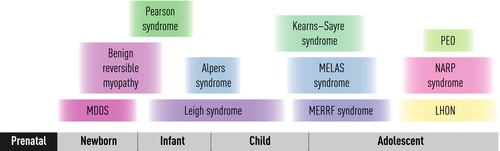

A clinical classification was the first rational classification of mitochondrial disease, since canonical syndromes with particular constellations of symptoms and signs had been recognized for decades before their genetic basis was understood [4–9]. A selection of these syndromes is described below, according to age at presentation (Fig. 1), and an ‘A to Z’ of mitochondrial syndromes is provided in Table 1. However, it is important to remember the enormous clinical heterogeneity of mitochondrial disease (Fig. 2) and that most children affected by mitochondrial disease do not have a classical syndromic presentation, particularly at the earliest stages of their disease when only a single organ may be involved.

Genetic complexity of mitochondrial disease

The genetics of mitochondrial disease is complex, with contributions from two genomes. Mitochondrial disease may be inherited by a number of different genetic mechanisms including maternal (mtDNA mutations) and autosomal recessive, autosomal dominant and X-linked for nuclear gene mutations. Sporadic mtDNA mutations have been recognized for more than three decades, but recently, an increasing number of de novo nuclear gene variants have been linked to mitochondrial disease, initially for DNM1Lvariants [119]. More recently, de novo variants have been reported in ATAD3A, CTBP1, ISCU, SLC25A4 and SLC25A24 [120]. DiMauro and colleagues were the first to classify the nuclear-encoded disorders rationally according to the underlying molecular defect [121]. Genetic causes of primary mitochondrial disease may be subdivided into defects of OXPHOS subunits and complex assembly, disorders of mitochondrial DNA maintenance, defects of mitochondrial gene expression, deficiencies of cofactor biosynthesis and transport, defects of mitochondrial solute and protein import, disorders of mitochondrial lipid membranes and organellar dynamics (fission/fusion) and disorders of mitochondrial quality control (Table 2), but new disease mechanisms continue to be discovered. Since the advent of next-generation sequencing methods, there has been a rapid pace of gene discovery for mitochondrial disease and currently approaching 400 different gene defects have been linked to primary mitochondrial disease.

Approach to diagnosis

When to suspect mitochondrial disease in childhood?

There are probably no absolutely pathognomonic clinical features of mitochondrial disease in childhood. Clinical presentations that should arouse suspicion of an underlying mitochondrial disorder include stroke-like episodes, acquired ptosis and/or ophthalmoplegia, sideroblastic anaemia and epilepsia partialis continua. However, it is frequently the combination of disease pathologies affecting multiple seemingly unrelated organs that triggers the clinical recognition of a mitochondrial disorder [122]. In other cases, the initial diagnostic clue may be a biochemical abnormality such as elevation of blood or CSF lactate, plasma alanine, urinary 3-methylglutaconic acid or other mitochondrial disease biomarkers [123]. Increasingly, a mitochondrial disorder is not suspected until potentially pathogenic genetic variants are identified in a known mitochondrial disease gene during next-generation sequencing of an exome or genome.

Importance of history taking

With so much focus on the enormous complexity of mitochondrial disease and the ‘differentness’ of it, the similarities to the rest of medicine may easily be overlooked. For example, very often the diagnosis rests in the history; careful attention to detail can allow the observant physician to win the diagnostic lottery. The patient, even a young nonverbal child, provides many clues about their personal story. The order of events is extremely important. What happened first? Was he or she born with the cataracts or squint or ptosis or did these features develop later? How does the mother, especially an experienced mother, feel about her child? Are things as expected? Or subtly different? So much of mitochondrial disease starts subtly, insidiously, in the first days and weeks of life. Did the baby not feed quite as well as they should, was there more than the usual amount of gastro-oesophageal reflux? Were they thrown off course by the mildest of infections? How do they compare to peers and siblings at the same age? Are developmental milestones being met? Has there been a loss of skills with intercurrent illnesses? Are they slower to recover from intercurrent illnesses than siblings, peers, other family members? How many systems are affected? It is important to enquire specifically about vision, hearing, language acquisition, cardiorespiratory and gastrointestinal symptoms, as well as about exercise tolerance, fatigue and the presence of migraines or seizures. Many children with mitochondrial disease do not have symptoms and signs that align closely with canonical mitochondrial syndromes (Table 1) but the pattern of organ involvement can be a powerful clue to the underlying diagnosis (Table 3). The family history may also provide useful diagnostic clues, for example if there is consanguinity, previous stillbirths or early neonatal deaths, or a strong history of problems running through the maternal lineage.

Physical examination

A thorough physical examination should be performed, including auxology and full neurological assessment, searching carefully for ptosis, ophthalmoplegia, optic atrophy or pigmentary retinopathy on fundoscopy, hypotonia, muscle weakness, dystonia, spasticity, extrapyramidal and cerebellar signs, and evidence of peripheral neuropathy. Muscle strength may be normal on static testing, and repeated testing may be needed to elicit the muscle fatigability typical of mitochondrial myopathy. Tachypnoea may be a clue to lactic acidosis, and there may be a hyperdynamic precordium if there is significant cardiomyopathy. A search for multisystem features should include assessment by a cardiologist (including ECG and echocardiography), ophthalmologist and audiological physician.

Diagnostic investigations

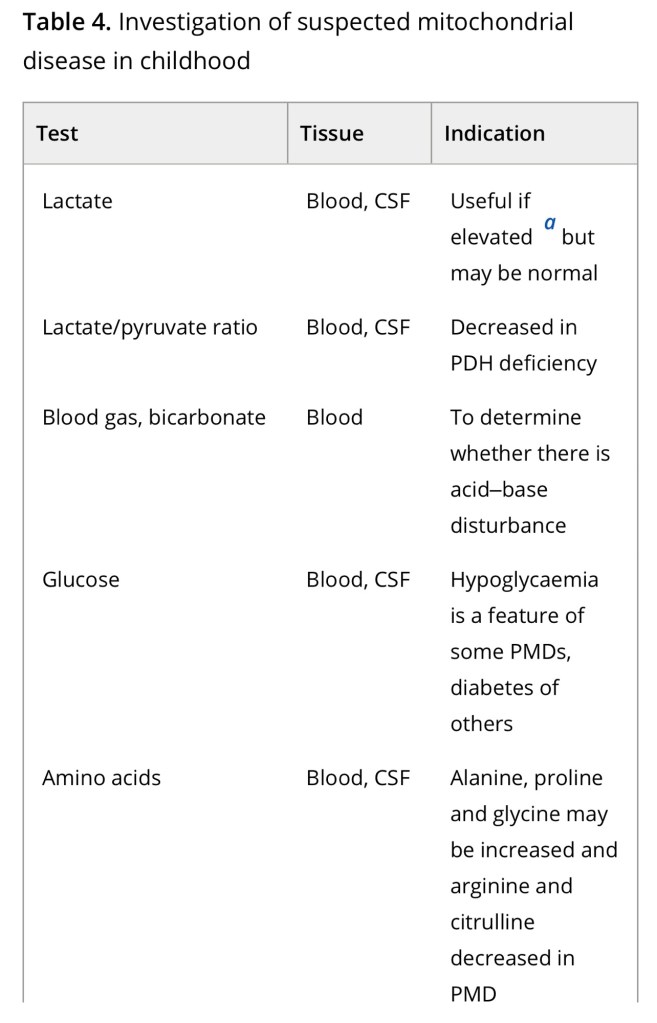

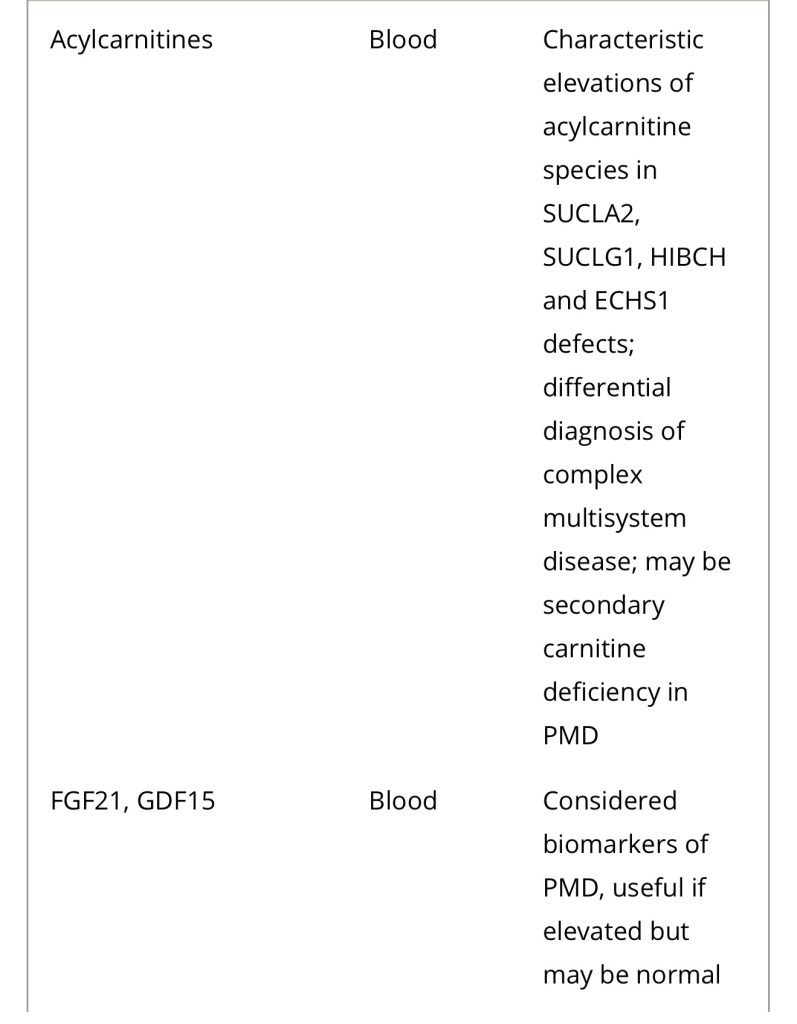

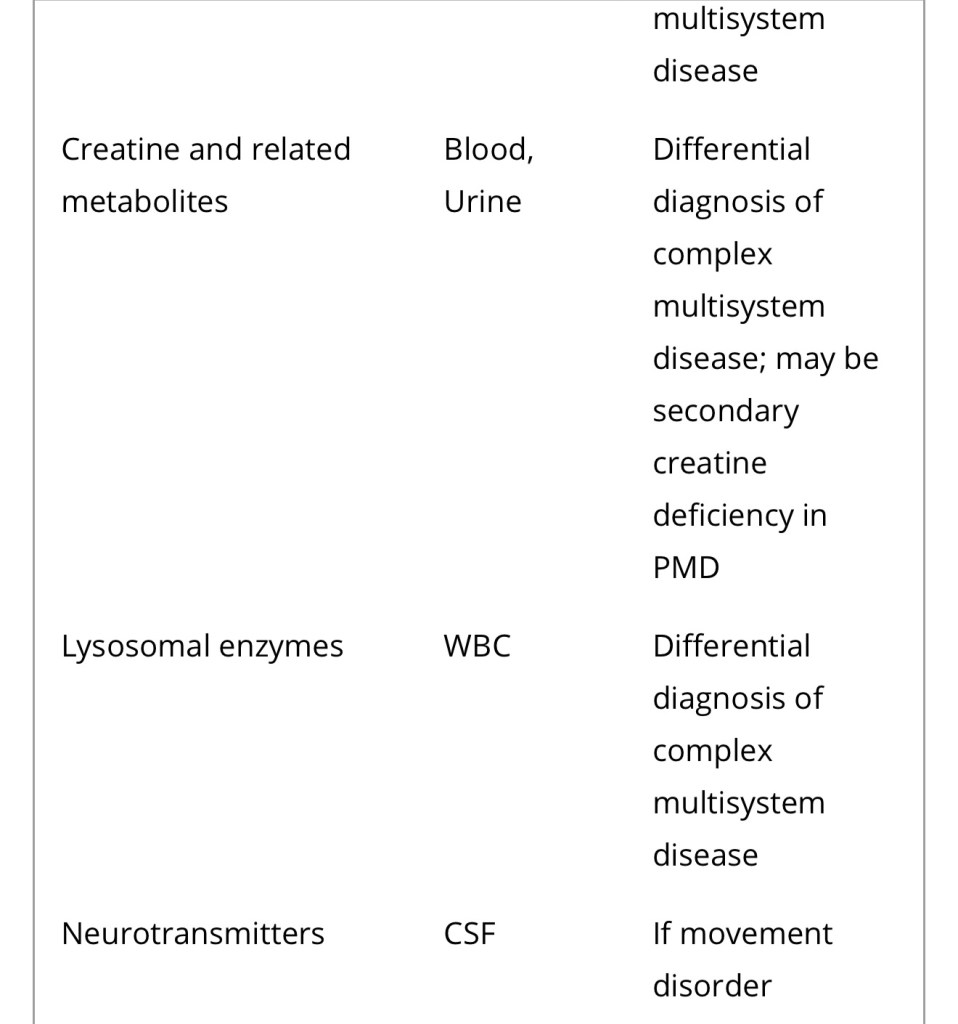

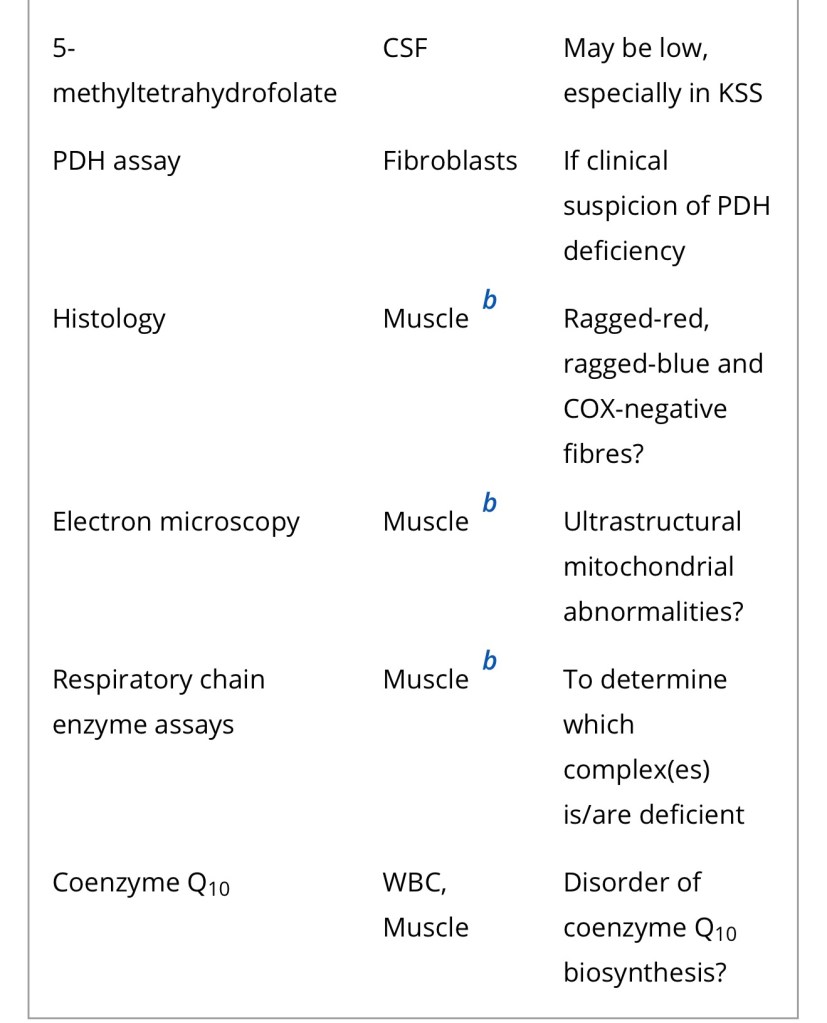

Diagnosis of a mitochondrial disorder requires a multidisciplinary approach, which may include metabolic investigations, neuroimaging, muscle biopsy and genetic testing. Blood, urine and CSF metabolites that can help in the delineation of a specific mitochondrial disorder or in the identification of a nonmitochondrial multisystem disorder (‘phenocopy’) are detailed in Table 4, together with a list of histological investigations and enzyme assays.

3MGA, 3-methylglutaconic aciduria; COX, cytochrome c oxidase; FGF21, fibroblast growth factor 21; GDF15, growth/differentiation factor 15; KSS, Kearns–Sayre syndrome; MNGIE, mitochondrial neurogastrointestinal encephalopathy; PDH, pyruvate dehydrogenase; PMD, primary mitochondrial disease; WBC, white blood cells.

a Providing secondary and artefactual causes of hyperlactataemia have been excluded.

b or other affected tissue.

Differential diagnosis and phenocopies

Mitochondrial diseases are notorious mimics, long recognized to present with any combination of symptoms affecting one or multiple organs at any age, from intrauterine life to late adulthood (Fig. 2). This phenotypic heterogeneity, coupled with the biochemical and genetic complexity of mitochondria, leads to enormous diagnostic challenges. Next-generation sequencing has introduced unparalleled opportunities for enhanced diagnosis of mitochondrial disease and led to the discovery of new disease genes at an astonishing rate, but has also revealed that mitochondrial dysfunction may in many cases be secondary to nonprimary mitochondrial genetic defects, leading to even more complexity [3]. Thus, mitochondrial disease could be thought of as a modern-day syphilis and Sir William Osler’s aphorism ‘Know syphilis in all its manifestations and relations, and all other things clinical will be added unto you’ [135] could be updated to ‘S/he who knows mitochondrial disease knows all of medicine’ to reflect the protean manifestations and complexity of mitochondrial disease.

“What about prognosis? Nothing, not the magnitude of lactate elevation in blood or CSF, the activities of respiratory chain enzymes in biopsied skeletal muscle, not even the definitive genetic diagnosis, can speak to a child’s prognosis as much as his/her own trajectory to this point in time. Has he or she slowly been making progress? Or progressively deteriorating and acquiring multisystem problems? Has there been developmental regression with intercurrent illnesses? Have they had a previous episode of respiratory failure necessitating intensive care admission? Whichever of these is true for an individual child, this is the likely trajectory of their disease going forwards. With the publication of a number of (largely retrospective) natural history studies in recent years, we can finally begin to add some more precise detail to these general observations, at least for some gene defects. It is sobering to note the continuing high mortality of paediatric mitochondrial disease. A systematic review of retrospective natural history studies reporting mortality data for 23 mitochondrial disorders revealed a mean/median age of death < 1 year in 13% of disorders, <5 years in 57% and < 10 years in 74% of the diseases studied [94].”

For any further reading:

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41392-024-02044-3

https://emorymedicine.wordpress.com/2024/05/02/euh-morning-report-review-of-mitochondrial-diseases/

Sources:

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/joim.13054

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41392-024-02044-3