Neglected Tropical Diseases (NTDs) wreck havoc among the poorest and most disenfranchised people in the world. The disproportionate burden of NTDs perpetuates poverty, ill health, and fosters conflict and political instability. Addressing and prioritising their elimination is fundamentally a humanitarian endeavour, driven by the principles of human rights, social justice and health equality.

The new Sustainable Development Goals explicitly target the NTDs; emphasising the need for universal health coverage and resolving to end the epidemics of communicable and NTDs by the year 2030.

The NTDs represent a diverse group of diseases; most are vector-borne, zoonotic, or associated with contaminated water. The definitions have evolved over time and vary between agencies but the key features remain:

- They affect almost exclusively poor and marginalised populations, and they have a disproportionately low profile among public health priorities and funding.

- All are endemic in the tropics, but many also occur among the marginalised and impoverished communities in temperate and wealthy countries.

- Although rural poverty is the most important determinant of NTDs, conflicts, forced migration and natural disasters, and other humanitarian emergencies can dramatically impact the transmission severity of NTDs

17 infectious diseases have been prioritised by the WHO and designated as official NTDs. However, there are many other diseases such as hepatitis E, cryptosporidiosis, and snake bite that share similar characteristics. These diseases have been neglected by our international community and require advocacy by humanitarian workers to address their burden among the populations that we seek to help.

Elimination and eradication of NTDs

Rather than control, WHO and partner agencies are increasingly calling for the elimination and eradication of NTDs.

WHO-endorsed strategic interventions to address NTDs

- Prevention chemotherapy and mass drug administration (MDA)

- Intensified case management

- Vector control

- Veterinary public services

- Improved access to clean water, sanitation and hygiene services

Dengue

Key features

- Dengue is the most rapidly spreading mosquito-borne viral disease in the world with 50-100 million infections per year.

- Most cases are mild but there are at-least 500,000 severe cases and 25,000 deaths per year.

- Supportive care and and IV fluids can reduce mortality of severe dengue from >20% to <1%.

Challenges

- Lack of vaccine and sustained global mosquito-control efforts.

- Presentation is non-specific and can mimic malaria, bacterial and other viral infections.

- Massive outbreaks can quickly overwhelm the healthcare systems.

- Dengue is an outlier among the 17 NTDs. It affects both rich and poor communities and has drawn increased public attention, and recent funding for vaccine development has increased exponentially.

- But, in common with NTDs, major implementation gaps still exist in surveillance and vector control. There is massive unmet need for global access to high-quality support clinical care for those with severe illness; similar to sepsis.

Transmission

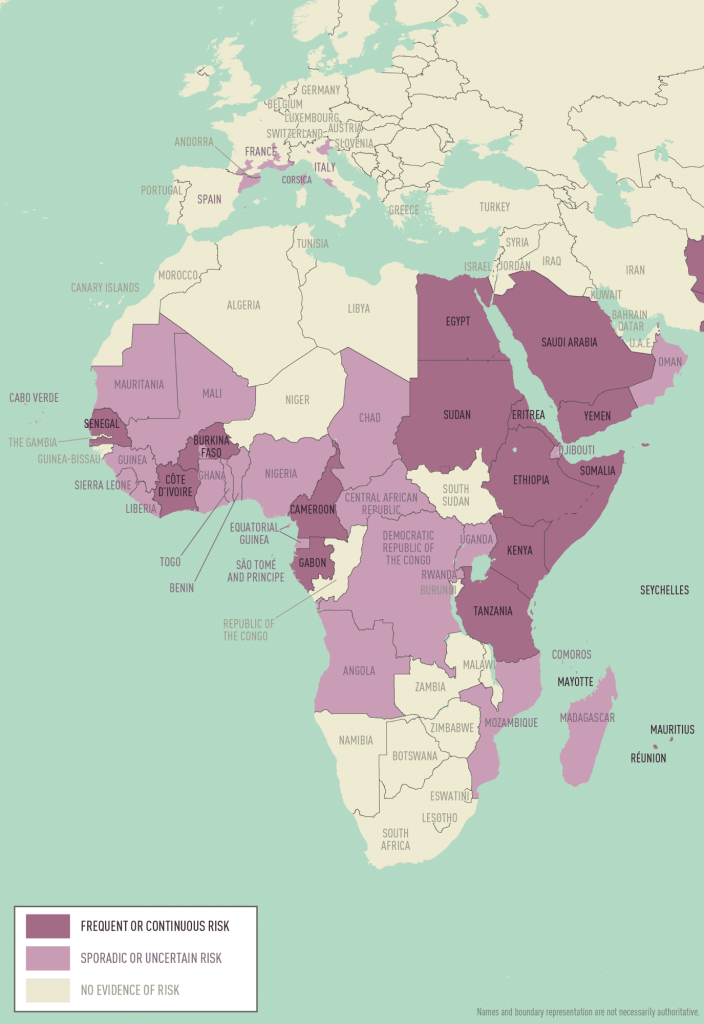

- Dengue is spread by Aedes mosquitoes-day biting, peri-domestic, and breed in rainwater in small discarded containers or old tyres.

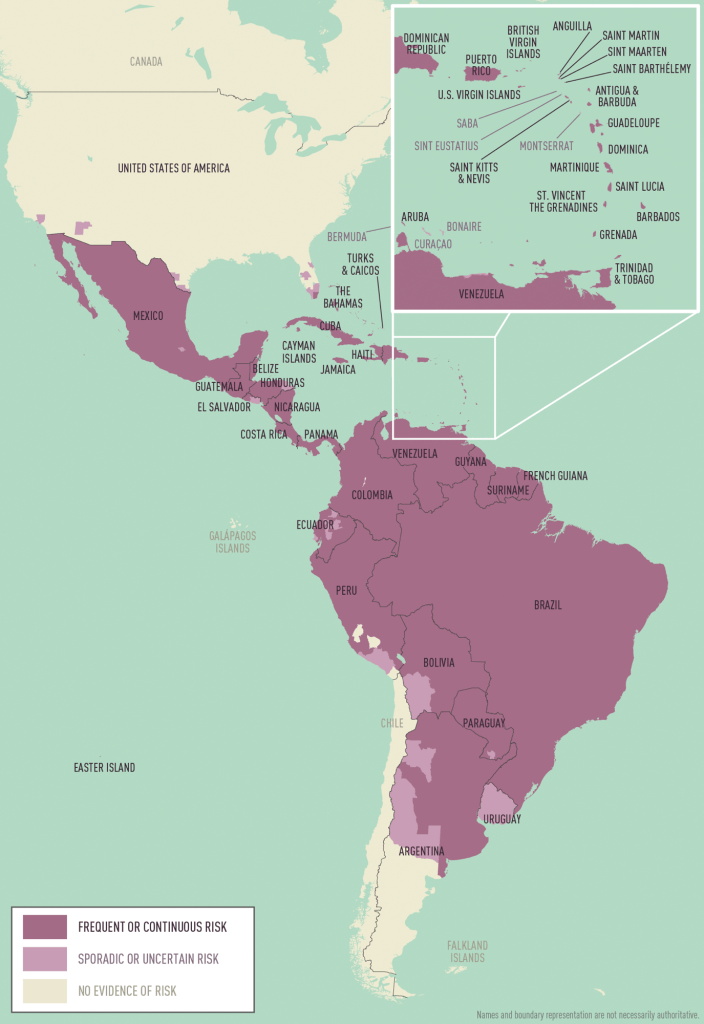

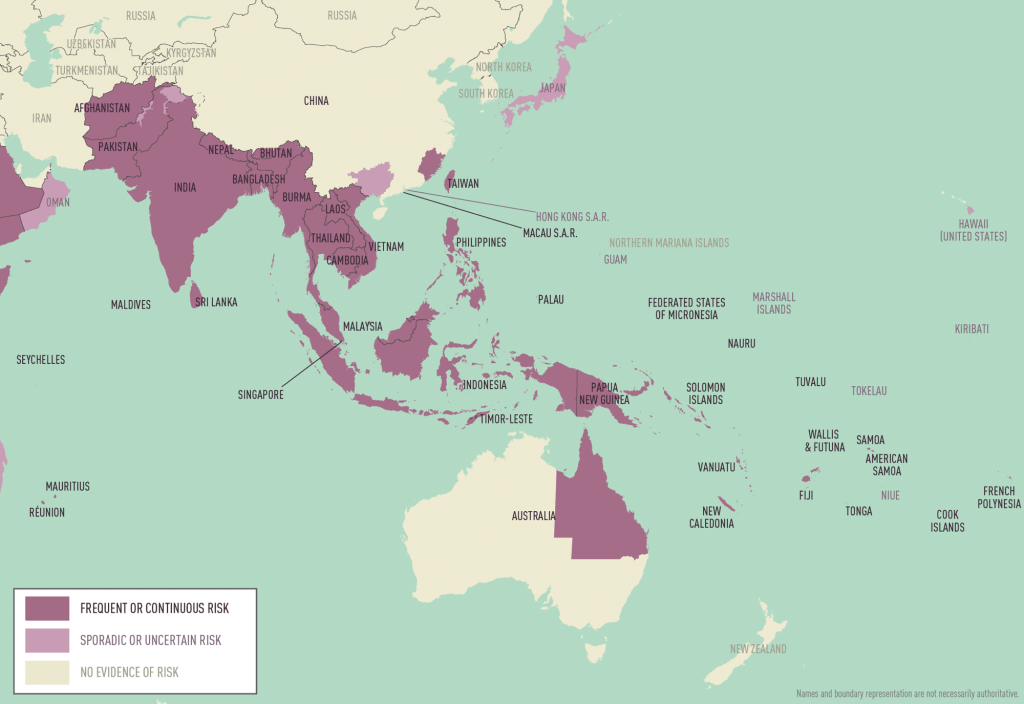

- Highest rates occur in urban/semi-urban Asia and Latin America.

Clinical features

Dengue can be clinically indistinguishable from malaria and bacterial and other acute viral infections. Classically it presents with acute-onset fever, headache, retro-orbital pain, and myalgia. Rash occurs in 50%.

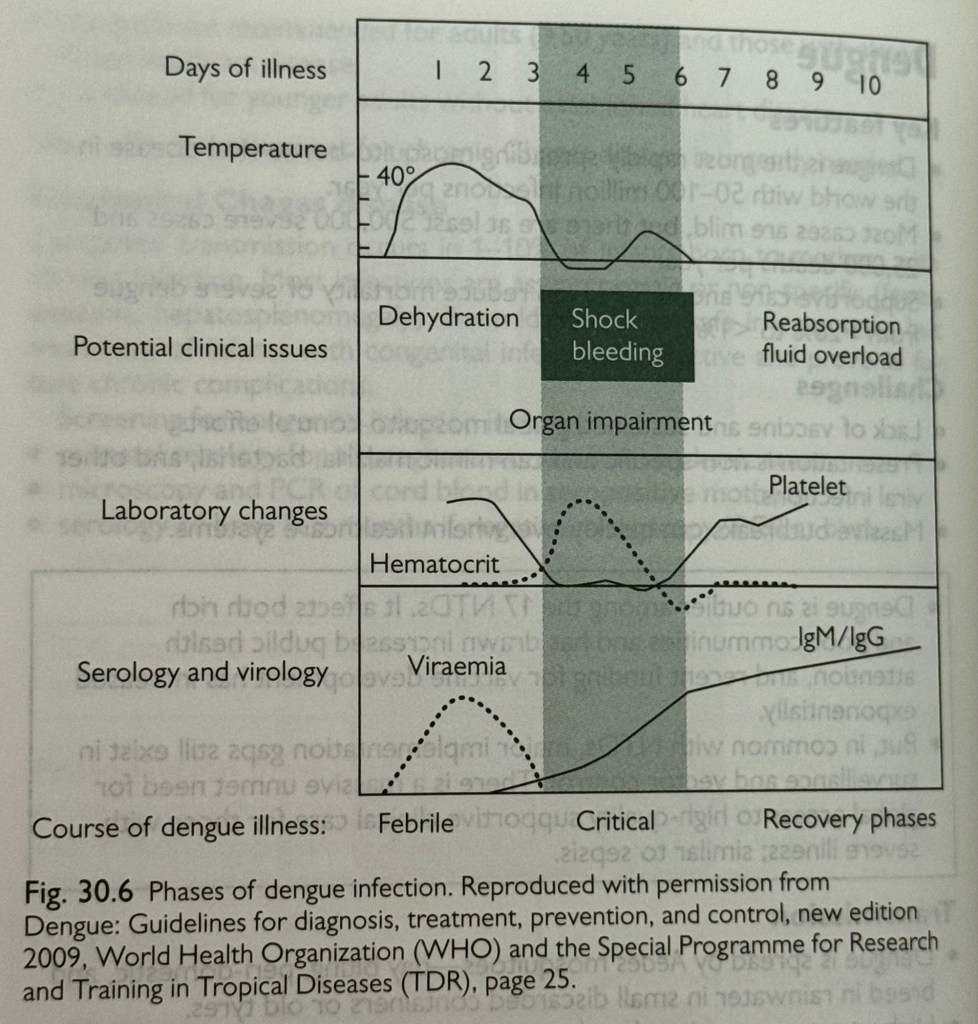

There are three phases of illness (see figure 30.6):

- Febrile phase, accompanied by high viraemia, lasts for 3-7 days.

- Critical phase coincides with resolution of fever and drop in viral load.

Although most patients improve, there is a transient increase in capillary permeability that can lead to plasma leakage and progression to severe illness in 5-10% of people. This is where intervention with IV fluids may be life-saving.

- Recovery phase is marked by a rise in the platelet count and resolution of plasma leakage.

Severe dengue versus dengue haemorrhagic fever

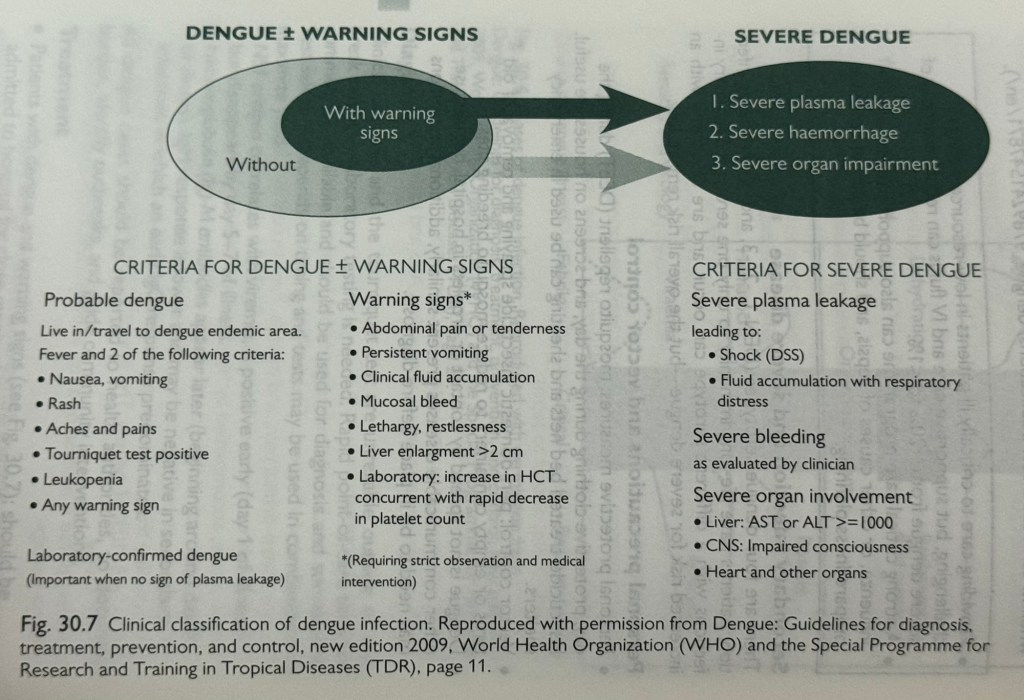

The new WHO classification system emphasises the recognition of plasma leakage rather than haemorrhage as the most important feature for clinical management of patients with dengue (Figure 30.7)

Diagnosis

Clinical diagnosis and tourniquet test are unreliable outside of outbreak settings—laboratory testing is needed. Rapid point of care tests are commercially available and should be used for diagnosis and surveillance. Test selection depends on timing and tests maybe used in combination to maximise yield.

- NS1 antigen correlates with viraemia, is positive early (day 1 of illness) but disappears by day 5-7 of illness.

- Immunoglobulin (Ig)-M antibodies appear later (beginning around day 5 of illness). Ig M response is lower and may be negative in secondary infections in which an early IgG response predominates.

All dengue cases should be reported to health authorities, to document burden, identify outbreaks, and guide community interventions.

Treatment

- Patients with dengue and warning signs (see Figure 30.7): should be admitted to hospital for close monitoring and supportive care.

- Monitor vital signs closely for signs of compensated shock.

-Narrowing of pulse pressure.

-Persistent tachycardia as fever drops.

- Follow Hct every 12-24 hours: a rise in Hct and a fall in platelets indicates plasma leakage, and need for IV fluids.

- Careful IV fluid therapy is critical to management of dengue shock

- Providing care to critically ill patients in low resource settings is challenging, but supportive care and IV fluids can reduce mortality of severe dengue from >20% to <1%.

- A strong critical care programme can also support patients with influenza, or other causes of sepsis, and should be part of epidemic preparedness planning.

Personal precautions and vector control

• Personal protective measures: mosquito repellant (DEET) during the day, protective clothing during the day, and screens on houses are useful. Insecticide-treated bed nets and sheeting can be used in emergency shelters.

• Vector control: peri-domestic insecticide spraying and removal of old tyres or empty containers to reduce mosquito breeding sites.

• Dengue is not spread by contact or droplets in hospital, but because other communicable diseases present similarly, additional precautions need to be in place before diagnosis.

Secondary infections and severe disease

There are four dengue serotypes DEN-1, -2, -3,-4. Following infection patients have life-long immunity to only one serotype. Secondary infections with a different serotype can occur, and are associated with an increased risk for severe dengue—but the overall risk remains low.

There’s a plea going out to several organisations to make a ‘World Dengue Day’ awareness. Signing this would bring us all, globally, a ‘World Dengue Day!’ You can sign the petition right here!👇🏻

https://www.isntd.org/world-dengue-day-open-letter

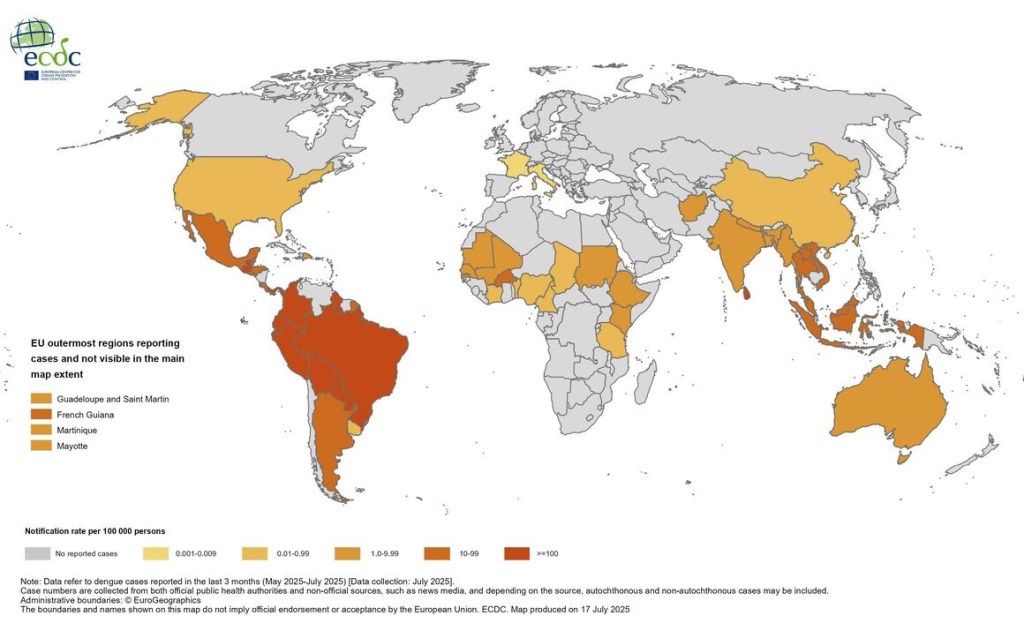

Situation update, July 2025

Since the beginning of 2025, 3.6 million dengue cases and over 1 900 dengue-related deaths have been reported from 94 countries/territories in the WHO Region of Europe (EURO), the Regions of the Americas (PAHO), SouthEast Asia and West Pacific (SEARO and WPRO, respectively), in the Eastern Mediterranean WHO Region (EMRO) and in Africa.

In the EU/EEA (excluding the outermost regions), four autochthonous cases have been reported in France and three in Italy in 2025. Cases have also been reported from the EU outermost regions.

Mosquitoes that can spread dengue usually live in places below 6,500 feet. The chances of getting dengue from mosquitoes living above that altitude are very low.

Nepal’s Current Dengue Scenario:

https://kathmandupost.com/health/2025/08/11/2-700-dengue-and-432-covid-cases-recorded-since-january

Entomological data on the spread of Ae albopictus in Europe:

https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lanplh/article/PIIS2542-5196(25)00059-2/fulltext

Current climate change driven dengue;

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2025/aug/12/dengue-fever-outbreaks-samoa-fiji-tonga-climate-crisis

Dengue Vaccines

• Currently 2 licensed dengue vaccines are available

- CYD-TDV (Dengvaxia), Manufacturer: Sanofi

- TAK-003 (Qdenga), Manufacturer: Takeda

CYD-TDY

-Consists of 4 live attenuated recombinant viruses (representing each of the 4 DENV serotypes)

-Vaccination schedule: 3 doses administered 6 months apart

-Age group: 9-45 years or 9-60 years (depending on the country specific regulatory approvals) living in dengue-endemic countries or areas.

-Clinical trials have shown CYD-TDV is efficacious and safe in persons who have had the dengue virus infection in the past (seropositive individuals) but increases the risk of severe dengue in those who experienced their first natural dengue infection after vaccination (seronegative individuals).

-Pre-vaccination screening for past dengue infection is the recommended strategy.

-Using this strategy, only persons of evidence with past dengue infections (based on an antibody test, or documented laboratory confirmation) would be vaccinated.

-If pre-vaccination screening is not possible, vaccination should be limited to areas that have recent documentation of seroprevalence rates of at least 80% by 9 years of age.

TAK-003

-Live attenuated tetravalent vaccine

-Vaccination schedule: 2 doses administered subcutaneously with an interval of 3 months between doses.

-Age group recommended: children aged 6-16 years in settings with high dengue transmission intensity.

-Until the efficacy risk profile for DENV3 and DENV4 in seronegative persons has been more thoroughly assessed, WHO does not recommend the programmatic use of TAK-003 vaccine in low to moderate dengue transmission setting

-Vaccine may not confer protection against DENV3 and DENV4 if the person is seronegative, and that there is a potential risk of severe dengue if seronegative individuals are exposed to DENV3 and DENV4.

Feasibility of Demgue vaccines in Nepal’s National Program

CYD-TDY

-Due to requirement of pre vaccination screening, it does not seem feasible to be implemented in Nepal.

-Risk of severe dengue if no past dengue infection.

TAK-003

-Recommended only for settings with high dengue transmission intensity.

-Vaccine may not confer protection against DENV3 and DENV4 if the person is seronegative, and that there is a potential risk for severe dengue if seronegative individuals are exposed to DENV3 and DENV4.

-In current scenario not feasible for Nepal.

⚠️International Warning⚠️:

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2025/aug/12/dengue-fever-outbreaks-samoa-fiji-tonga-climate-crisis

WHO Guidelines for clinical management of arboviral diseases: dengue, chikungunya, Zika, and yellow fever

https://app.magicapp.org/#/guideline/10368

WHO’s Global Dengue Surveillance System is right here;

https://worldhealthorg.shinyapps.io/dengue_global/

Forecasting Disease Trends using Nepal’s Case Study:

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-025-94527-8?fromPaywallRec=false

Knowledge, Attitudes and Practices on Dengue in Asian Households;

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41599-025-05017-1

Signing off,

Nivea Vaz

Campaign Ambassador for Dengue Search & Destroy

Source:

Oxford Handbook of Humanitarian Medicine

WHO-SEARO Facebook Page

Dengue Presentation New.pptx

https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/dengue-monthly

https://www.cdc.gov/dengue/areas-with-risk/index.html

https://www.cdc.gov/yellow-book/hcp/travel-associated-infections-diseases/dengue.html