It’s Beginnings & It’s History

Since the time of ancient Egypt, plants containing cyanide derivatives, such as bitter almonds, cherry laurel leaves, peach pits, and cassava, have been used as lethal poisons. Peach pits used in judicial executions by the ancient Egyptians are on display in the Louvre Museum, Paris, and an Egyptian papyrus refers to the “penalty of the peach.” The Romans used cherry laurel leaves as a method of execution (also known as “the cherry death”), and the Roman emperor Nero used cherry laurel water to poison members of his family and others who displeased him. Dioscorides, a Greek physician who served in Nero’s army, compiled information on more than 600 species of plants with medicinal value in the five books titled De Materia Medica, recognizing the poisonous properties of bitter almonds. Napoleon III proposed the use of cyanides to enhance the effectiveness of his soldiers’ bayonets during the Franco–Prussian War; it has also been suggested that Napoleon died from cyanide.

The first description of cyanide poisoning, by Wepfer in 1679, dealt with the effects of extract of bitter almond administration. In 1731 Maddern demonstrated that cherry laurel water given orally, into the rectum, or by injection, rapidly killed dogs. Although substances containing cyanide have been used for centuries as poisons, cyanide was not identified until 1782, when Swedish pharmacist and chemist Carl Wilhelm Scheele isolated cyanide by heating the dye Prussian Blue with dilute sulfuric acid, obtaining a flammable gas (hydrogen cyanide) that was water soluble and acidic. Scheele called this new acid Berlin blue acid, which later became known as prussic acid and today is known as cyanide (from the Greek word “kyanos,” meaning “blue”). Scheele’s discovery may have cost him his life several years later, from either engaging in unsafe experimental practices such as taste testing and smelling HCN, or accidentally breaking a vial of the poison. A better understanding of the cyanides was achieved in 1815 by the French chemist Joseph Louis Gay-Lussac. Gay-Lussac identified a colourless, poisonous gas called cyanogen, which had an almond like flavour and considerable thermal stability. His work on acids, including HCN, led to the realization that acids do not need to contain oxygen, and that the cyanogen moiety could be shifted from compound to compound without separating the individual carbon and nitrogen atoms.

Military, Suicides & Homicides

During World War II, the Nazis employed HCN adsorbed onto a dispersible pharmaceutical base (Zyklon B) to exterminate millions of civilians and enemy soldiers in the death camps. Cyanide was detected in the walls of crematoria almost 50 years later. One notorious incident was the poisoning of Tylenol (acetaminophen, manufactured by McNeill Consumer Products Co, Fort Washington, Pa) in the Chicago area in 1982, which killed seven people. An acid and a cyanide salt were found in several subway restrooms in Tokyo, Japan, in the weeks following the release of nerve agents in the city in March 1995.

Cyanide has been the typical agent used in “gas chambers,” in which a cyanide salt is dropped into an acid to produce HCN. Gas chambers used in some states to judicially execute murderers provide information on the effect of HCN. In US gas chambers HCN was usually released by dropping a bag of sodium cyanide into sulfuric acid. Unconsciousness was thought to be instant, with death following in 5 to 10 minutes. It’s commonly thought that Hitler committed suicide by shooting himself in the head, evidence has suggested that he in fact killed himself via use of a pill containing potassium cyanide, along with his mistress Eva Braun.

It’s Mechanisms

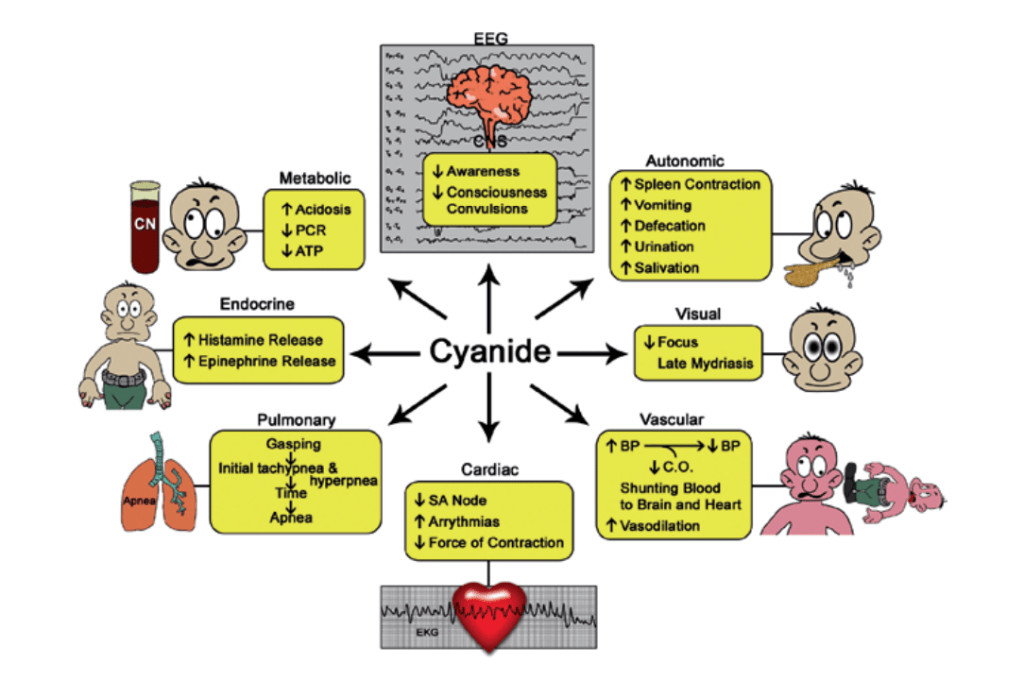

Cyanide is known to bind and inactivate several enzymes, particularly those containing iron in the ferric (Fe3+) state and cobalt. It is thought to exert its ultimate lethal effect of histotoxic anoxia by binding to the active site of cytochrome c oxidase, the terminal protein in the electron transport chain located within mitochondrial membranes. By this means, cyanide prevents the transfer of electrons to molecular oxygen. Thus, despite the presence of oxygen in the blood, it cannot be utilized toward adenosine triphosphate (ATP) generation, thereby stopping aerobic cell metabolism. Initially cells attempt to replenish the ATP energy source through glycolysis, but the replenishment is short lived, particularly in the metabolically active heart and brain. Binding to the cytochrome oxidase can occur in minutes. A more rapid effect appears to occur on neuronal transmission. Cyanide is known to inhibit carbonic anhydrase,and this enzyme interaction may prove to be an important contributor to the well-documented metabolic acidosis resulting from clinically significant cyanide intoxication.

If analysis of cyanide cannot be performed quickly, then the sampling and storage of biological samples for later testing should consider the following:

• Cyanide resides mainly in erythrocytes rather than plasma.

• Cyanide may evaporate because of HCN volatility at the physiological pH, and cyanide nucleophilic action should be reduced.

• Cyanide may form during storage.

When selecting an analytical method, several factors in addition to the detection limit and length of time needed must be considered:

• Does the method include consideration of preserving cyanide and its metabolites during storage?

• Does the method include correct storage of stock solutions or use fresh preparations daily?

• Does the method include consideration of typical interferences found in blood?

• Does the method test for cyanide with and without clinically used antidotes present?

• Does the method include analysis procedures (e.g., pH, heating, and acidification) that could result in the loss of cyanide? Are rubber stoppers or septums used?

• Are the chemicals used in the determination toxic or carcinogenic?

• Is the method precise, accurate, inexpensive, and practical?

Common themes in case presentations (acute, severe) include rapid onset of coma; mydriasis with variable pupil reactivity; burnt/bitter/pungent almond scent; tachycardia; metabolic acidosis, often extreme; cyanosis of mucous membranes and/or flushed skin; absence of cyanosis despite respiratory failure; ECG showing the T wave originating high on the R (most severe); absence of focal neurological signs; distant heart sounds; an irregular pulse; and similar oxygen tension in both arterioles and venules. In a few cases of massive poisoning, pulmonary oedema has been reported, likely a result of myocardial injury from the cyanide leading to temporary left heart failure and increased central venous pressure.

Another uncommonly reported acute complication is rhabdomyolysis.

Diagnosis:

1. Arterial blood gas analysis may reveal metabolic acidosis and elevated lactate levels.

2. Measurement of cyanide levels in blood or body fluids can aid in confirming the diagnosis.

General advantages and disadvantages of each antidote are listed in Table 11-5; however, objective comparison of antidote efficacy is hampered by the following factors:

• the number of patients is small;

• most cyanide victims receive several treatment agents;

• readily available, adequate analysis of blood and tissue concentrations are lacking; and

• limited comparison studies are available in animal models.

Sources:

http://askdis.blogspot.com/2017/03/management-of-cyanide-poisoning.html?m=1