In Cassidy v Ministry of Health (Fahrni, Third Party)[1951] 1 All ER 574, p 588, Denning LJ said:

In my opinion, authorities who run a hospital, be they local authorities, government boards, or any other corporation, are in law under the self-same duty as the humblest doctor. Whenever they accept a patient for treatment, they must use reasonable care and skill to cure him of his ailment.

There is no doubt that once the relationship of doctor and patient or hospital authority and admitted patient exists, the doctor or the hospital owe a duty to take reasonable care to effect a cure, not merely to prevent further harm. The undertaking is to use the special skills which the doctor and hospital authorities have to treat the patient.

The relationship between law and medicine (or, more generally, between law and healthcare) can sometimes be antagonistic. But law is not just there to catch healthcare professionals out or to call them to account. At a minimum, law offers rules that seek to guide people’s behaviour. The rules perform a variety of functions, including setting out rights, entitlements and obligations, laying down conditions, and facilitating relationships. Of course, how the law does all this, and the terms in which it seeks to do so, can be bewildering.

The word ‘logonomocentrism’ attempts to depict law as a coherent, unified, and rational body of rules; a jigsaw puzzle, all the pieces of which are present and slot neatly together.

Many legal scholars would agree that law should aspire to the values implied in logonomocentrism; after all, if law is to have any purchase in the real world, by serving to guide people’s behaviour, then it should be consistent and grounded in reason. But the real world also shows us that law is much more complex and fragmented than this; it can indeed be puzzling, as the pieces of law’s puzzle are sometimes missing or misplaced and even the all-important edges can be hard to locate.

How, then, can non-lawyers—such as doctors or medical students—hope to grasp what it is that the legal puzzle requires of them?

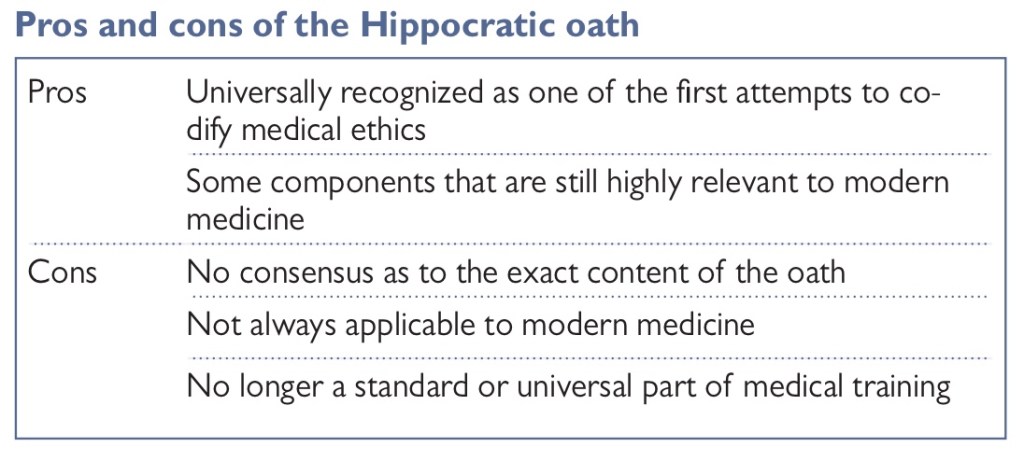

The Hippocratic oath

Many people are familiar with the idea that doctors take a solemn oath, in which they promise to behave ethically and in accordance with the moral standards required for the practice of medicine.

How useful is the Hippocratic oath?

In terms of providing answers for the questions raised by modern medical practice, the Hippocratic oath is limited for several reasons:

➮ There is dispute as to what the Hippocratic oath actually is. There are several texts that lay claim to being the oath, but there is little consensus as to which of these texts is the ‘real’ oath.

➮ although many trainee doctors do take an oath, the content is widely variable, and the oath is not a standard or essential part of medical training or practice, either in the UK or beyond.

➮ The fragments of text that are regarded as being part of the original oath are very much a product of their time. Much of the text focuses on the medical student’s obligations to respect the wisdom and authority of the master.

Ethical Theory

Similarity between ethical and scientific theories

Scientific theories aim to predict and explain events, whereas ethical theories aim to recommend or forbid certain courses of action: to provide us with moral reasons for doing things. As with scientific theories, there may be a number of ethical theories that provide reasons that explain or justify certain phenomena— sometimes these theories will work together smoothly; at other times, they may conflict with one another.

Sometimes a new theory may emerge that seems to solve or reconcile some of these conflicts. One of the most difficult aspects of ethics is that in the absence of proof, we tend to look to our intuitions to verify whether a particular course of action is acceptable. However, as we know from other areas of life, intuitions are not always reliable. It is because of this that ethical analysis is so important.

Is ethical theory a necessary part of making ethical decisions?

Knowledge of ethical theory is not an essential part of this process. However, in situations of extreme complexity, or when disputes arise, it can be helpful to be familiar with ethical theory.

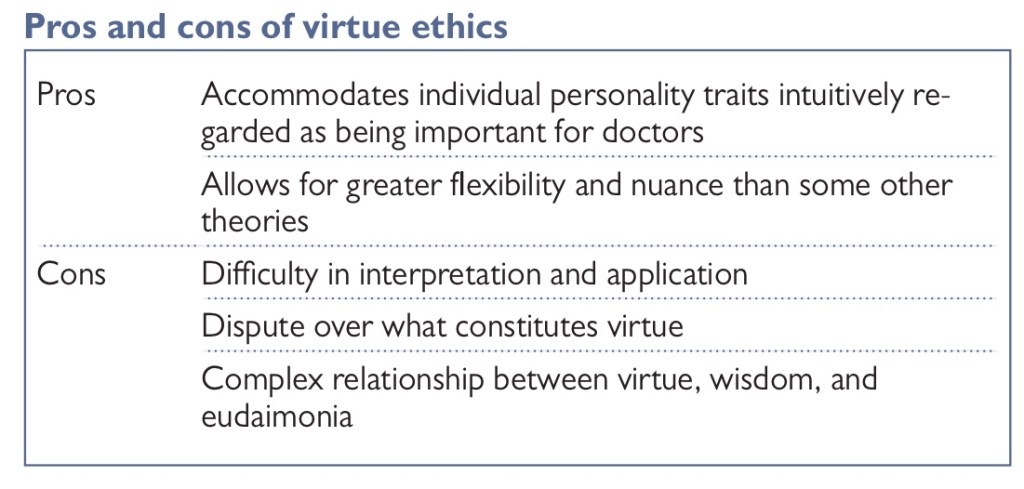

Virtue ethics

Aristotle’s ethical theory revolves around a number of key concepts, including virtue, practical wisdom, and eudaimonia (human flourishing). Perhaps the most familiar of these is the concept of virtue. For Aristotle, the way to find the right course of action is to look not at the action in itself, but at the kind of person who is making the decision. A virtuous person will make a good decision, but it is by recognizing the virtues of the person, rather than by analysing the act itself, or its outcome, that we know it is right.

Virtue ethics is now regarded as being one of the three key moral theories, along with consequentialism and deontology.

Virtue ethics in practice

⦿ Wisdom

The most valuable of all the virtues is wisdom. It is wisdom that enables the virtuous person to recognize the appropriate balance between extremes, in any particular situation.

⦿ Eudaimonia

Another important aspect of virtue ethics is the concept of eudaimonia. Some Greek philosophers, such as Epicurus, suggest that happiness or pleasure is the supreme moral goal. If this is true, it seems mean that we should pursue pleasure by the quickest and most direct means. Eudaimonia is commonly translated as ‘human flourishing’, and it encompasses all of the capabilities that are associated with being a person: not just immediate pleasure, but long- term endeavours such as education, art, and culture.

⦿ Justice

A further element of Aristotle’s moral philosophy to consider here is the question of justice. Aristotle famously said that justice means ‘treating equals equally and unequals unequally’.

How should medical practice and medical law be structured with respect to the intentional taking of human life by members of the medical profession?

As we will see, a sound answer to this question requires consideration of the so- called Principle of Double Effect.

Fairness and the Golden Rule

A second norm that is implied by the first principle of morality relates to fairness and the so- called Golden Rule. . For doctors and patients, the common good is the patient’s health; for families, it is the overall welfare of the family members individually and as a unit; for a political society, it is the totality of conditions necessary for citizens to pursue upright and flourishing lives, individually, and in community (communities) with one another. Fairness ought normatively to structure all of these cooperative pursuits so that the distribution of benefits and burdens, understood ultimately by reference to the basic human goods, does not arbitrarily favour some at the expense of others. Failures in this respect will result in injustices in the relevant communities; success will protect opportunities for genuine human flourishing. The norm of fairness will be essential to the discussion of beginning and end- of- life ethics below (much, though not all, killing is unfair); and to the discussion of the right to health care in a political community.

Double Effect

‘You ought never to cause harm as a side effect’, for ought implies can, and it is impossible always to avoid causing harm as a side effect. There thus emerges, in the course of the natural law tradition, the Principle of Double Effect. Put simply, an effect that would always be wrong to intend (eg harming the basic goods of life and health) can sometimes (though not always: more on that in a moment) be permissible if brought about as a side effect if there is a proportionate reason for permitting it. More traditional formulations articulate four parts to the rule: that the act be permissible in itself; that the evil effect not be intended; that the good effect not come about through the evil effect; and that there be a proportionate reason for accepting the bad effect in pursuit of the good.28

What is a proportionate reason?

This can be answered in one way by returning to the case of abortion. In cases of vital conflict, where both the mother’s and the child’s life are at stake, natural law theorists have considered it permissible to remove the child (eg in a hysterectomy of a cancerous uterus) to save the mother. The child’s death is not intended: it is neither an end nor a means. It is rather an accepted side effect. That side effect is considered proportionate because it is fairly accepted: it passes the test of the Golden Rule. By contrast, even if we assume, with Judith Jarvis Thomson, that there exist abortions that are merely expellings, with death as a side effect, that side effect will typically be disproportionate—unfair— if done for reasons less grave than preservation of the mother’s life.

Double effect-Prescribing (or giving) opiates with the intention of alleviating pain, but with the possible ‘side effect’ of shortening life, is therefore lawful, under the so- called ‘doctrine of double effect’.

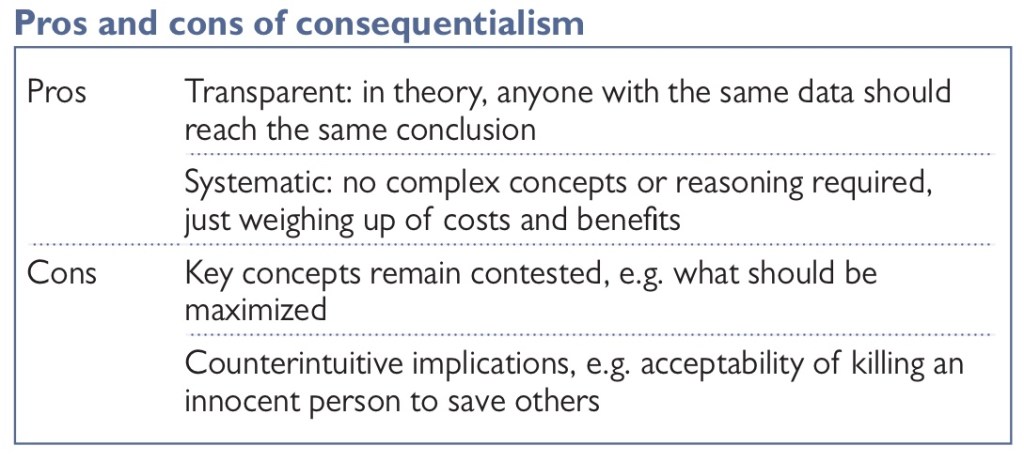

Consequentialism

There are two broad schools of ethical theory: consequentialism and non- consequentialism.

According to consequentialism, the right act is that act which has the best consequences. According to non- consequentialism, the rightness of an action is not solely determined by its consequences (although most versions of non- consequentialism allow some ethical rele-vance of consequences). The most famous version of non-consequentialism is deontology, which holds that one has an absolute duty to obey certain rules. ‘Never kill an innocent person’ or ‘never lie’ are examples of such rules. Christianity is one form of deontology and the Ten Commandments represent one set of rules.

Elements of Consequentialism

Consequentialism is a theory of right action. It instructs the agent to outline all the possible actions, including doing nothing at all. One must then assign a value to the possible outcomes of each action, and a probability for each of these outcomes occurring. The expected value of each action is the sum of the value of the outcomes of each action, where each value is multiplied by the probability of it eventuating. The agent should choose that act with the greatest expected value.

There are two key components to consequentialism:

(1) The probability of outcomes occurring. These should be based on the best evidence available. Thus, consequentialism sits naturally with scientific approaches to medicine and evidence- based medicine.

(2) The value of the outcomes. This is a distinctively ethical evaluation of the good.

Consequentialists care only about the consequences, not how they were brought about. This is often caricatured by the following phrase: ‘The end justifies the means.’ Consequentialists reject any distinction between intended and foreseen effects. What matters is the predicted outcome of an action, and whether that is justified, not the intent. Accordingly, consequentialists are typically sceptical of the doctrine of double effect.

Consequentialism thus faces at least three challenges:

(1) to define what is of value;

(2) to determine what the probability is of various outcomes occurring; and

(3) to compare the expected value of different courses of action.

Given the wide disagreement about what constitutes a good life and a life worth living, the least controversial account of a life not worth living is one which is not worth living on all three accounts:

(1) balance of pain over pleasure;

(2) greater desire frustration than fulfilment; and

(3) lack of any objective goods or objectively valuable activity in life.

Disability will be relevant to these three criteria, but we cannot say what its precise effect will be on welfare or well- being, out of the specific context, and especially the social and technological context. A life with loving and devoted parents may tip the balance of pleasure over pain.

The most famous form of consequentialism is utilitarianism: ‘an act is morally right if it maximizes the good’ (the terms consequentialism and utilitarianism are commonly used interchangeably). The simplicity of this approach to ethics has a clear appeal. Once we have determined what constitutes a good outcome, we need only to establish what consequences will follow from two options to know which of them is ethically preferable.

Good consequences

Consequentialism is attractive partly because once we have decided what counts as a ‘good’ consequence, we do not need to trouble ourselves further with morally complex principles or concepts. We can simply go out and measure outcomes. For this reason, consequentialism is often regarded as an intrinsically rational, empirical, and almost scientific approach to ethics. More fundamentally, perhaps, utilitarianism appeals to a deep intuition that is shared by many people, that the results of our choices are morally significant, and that an act that benefits many people, and harms no one, is better than an act that harms many people and benefits no one.

Consequentialism and public health

Consequentialism poses challenges for the doctor– patient relationship since it explicitly requires doctors to consider the greater good— not just the interests of a specific patient. However, in the public health context, consequentialism has an important role to play. Measures such as cervical screening tend to be evaluated on the basis of how many lives they save, a broadly consequentialist approach. For example, the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) uses the quality- adjusted life year (QALY) to determine whether healthcare interventions can be justified or not on the basis of cost per (quality- adjusted) year.

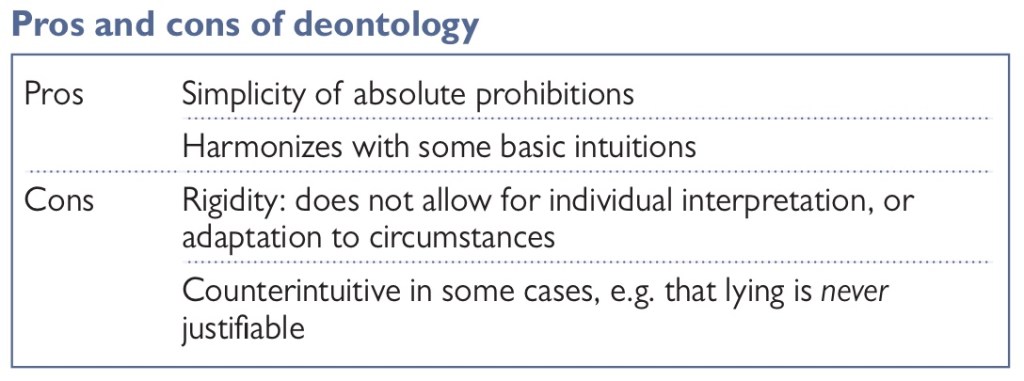

Deontology

Deontological ethics is typically traced back to Immanuel Kant and is for this reason also called Kantian ethics. Deontology (from Greek deon, meaning ‘duty’) falls within the domain of moral theories that guide choices of what is morally required (leges praeceptiva), forbidden (leges prohibitivae), or permitted (leges permissivae), as a matter of duty, obligation, or responsibility (I use these words interchangeably here). Deontological or Kantian ethics guides choices and defines actions based on the rightness or wrongness of the action in and of itself, rather than defining the rightness or wrongness of an action based on the consequences of said action.

What can deontological ethics offer to contemporary medical law and bioethics? The current discussions in contemporary medical law and bioethical debates have been almost exclusively concerned with and framed around the autonomy of patients and their individual rights.

In contrast to consequentialism, a deontologist approaches ethical questions by identifying and adhering to moral rules, or duties. Once we have established what our duty is, we must perform it, regardless of what the outcome may be. However, this does raise the question of how we establish what our duties are. Often, deontological approaches are associated with religion (the Ten Commandments are a set of deontological rules) but religious duties cannot easily be imposed on those who do not share that religion. And if moral duties are derived simply from religious obligations, it seems to lead us into a logical difficulty. In Plato’s Euthyphro dilemma, we are asked whether the gods approve of what is good, because it is good, or whether what they love is good because they approve it. Neither answer seems satisfactory.

Duties and reason: the categorical imperative

The German philosopher Immanuel Kant argues that we can establish our moral duty purely through the exercise of reason without having to derive them from any theological source. This is known as ‘the categorical imperative’.

Dignity and human rights

Deontological morality is often associated with the language of human dignity and human rights. Because it imposes absolute prohibitions on the ways in which we can treat other people, this seems to imply that human beings are imbued with a special moral significance. This may be termed as ‘dignity’.

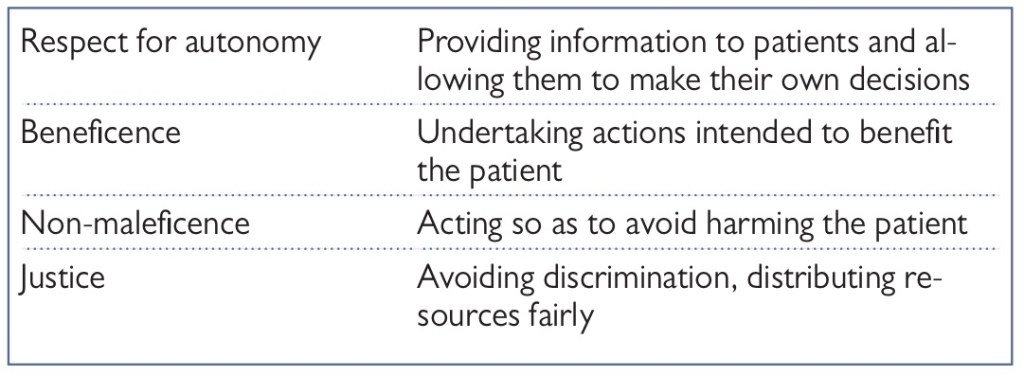

The Four Principles

What should be done if doctors’ views and values differ from those of patients? How should doctors deal with ethical problems that arise in medical practice— does the Hippocratic oath really provide all the answers we need? Or can we perhaps rely on ethical theories such as those outlined in previous chapters?

After the Nuremberg Trials, many nations began to feel that a universal framework was needed, to which all people could subscribe, and within which doctors could practise ethically. This has led to a range of international protocols, notably the International Council on Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Registration of Pharmaceuticals for Human Use, Good Clinical Practice (ICHGCP), which ensures clinical trials of pharmaceuticals are rigorous and protect the rights of research participants.

The principles in question are:

As suggested, these principles are not to be regarded an ethical theory in their own right. They are more properly understood as a distillation of other ethical theories, synthesized and reformatted for use in the medical setting.

➊Autonomy means self- governance: making and carrying out one’s own decisions.

➋Beneficence is the act of helping people, or benefiting them.

➌Non- maleficence is the principle of preventing or avoiding harm to others.

➍Justice is the principle of treating others fairly, avoiding discrimination and distributing resources equally.

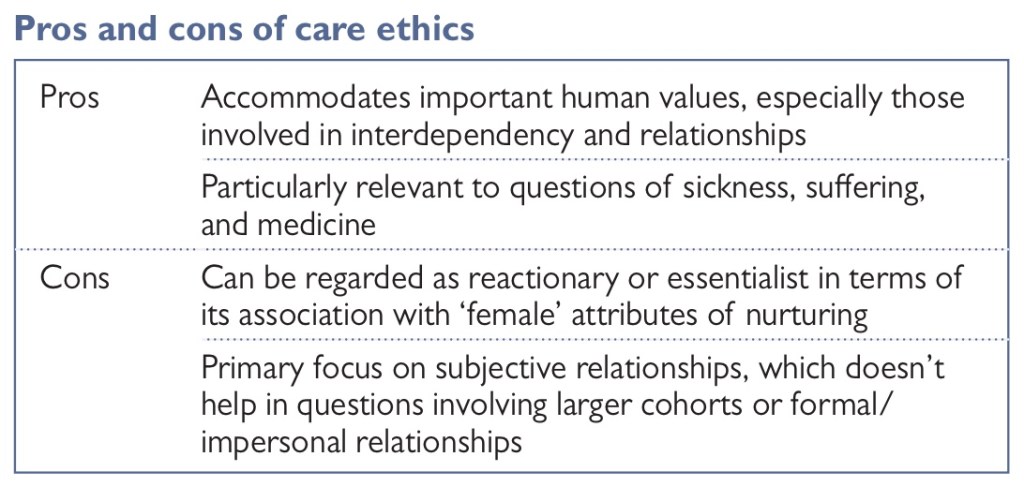

What is care ethics?

Care ethics offers a more relationship- focused approach to ethics. One which takes into account emotion and interdependency— both key features of a characteristically human life.

Negligence

ⒶNeglect This requires a gross failure to provide the very basics of life, such as nourishment, liquid, warmth, or medicine to someone in a dependent position.

ⒷNegligence* Carelessness amounting to the culpable breach of a duty; failure to do something that a reasonable man (i.e. an average responsible citizen) would do, or doing something that a reasonable man would not do. In cases of professional negligence, involving someone with a special skill, that person is expected to show the skill of an average member of his profession.

ⒸNegligence claim A negligence claim requires the patient to establish on the balance of probabilities that he or she was owed a duty of care; that the duty was breached (the doctor fell below the appropriate standard of care and was negligent); and that the breach of duty caused harm to the patient.

ⒹGross negligence* A high degree of negligence, manifested in behaviour substantially worse than that of the average reasonable man. Causing someone’s death through gross negligence could be regarded as manslaughter if the accused appreciated the risk he or she was taking and intended to avoid it but showed an unacceptable degree of negligence in avoiding it.

ⒺInformation disclosure negligence Where patients suffer an injury as a result of medical treatment, they may claim that if they had been properly informed they would not have consented to the treatment, and so would have avoided the injury. This legal action is based on negligence. In other words, it is alleged that the practitioner failed in his or her duty of care to the patient, in this case by not providing sufficient information.

ⒻTort* A wrongful act or omission for which damages can be obtained in a civil court by the person wronged, other than a wrong that is only a breach of contract. The law of tort is mainly concerned with providing compensation for personal injury and property damage caused by negligence.

Civil Liability

In English law where someone suffers an injury (physical or psychiatric) as a result of another person’s negligence, the injured person can bring a claim for compensation both for the injury itself and for any consequent financial loss. To succeed in a claim for personal injury, the claimant must prove: (a) that the defendant is in breach of duty (i.e. has acted negligently or in breach of a statute); and (b) that the claimant’s injury was caused by that breach. The general rule is that claims for personal injury must be brought within 3 years of the date of injury, or the claimant’s date of knowledge of the injury. However, this can be extended in certain circumstances. These principles apply as much in the context of medical treatment as in any other context (road accident claim, employers’ liability claims, etc.). However, a number of special rules apply to clinicians.

Breach of Duty

The classic test of whether a clinician has acted negligently was set out in the case of Bolam v Friern Hospital Management Committee [1957] 1 WLR 582.

A doctor is ‘not guilty of negligence if he has acted in accordance with a practice accepted as proper by a responsible body of medical men skilled in that particular art’.

In practical terms, this means that, even if a majority of doctors would not defend the clinician’s decision (to give a particular treatment, or to withhold a particular treatment, or to perform a procedure using a particular method, etc.), provided that some responsible doctors would have made the same decision, the clinician is not guilty of negligence.

There are two important caveats to this test.

In 1997 (in the case of Bolitho v City & Hackney Health Authority [1998] AC 232) the House of Lords held that, in ‘rare cases’, if it had been demonstrated that the professional opinion defending the doctor’s action was incapable of withstanding logical analysis, the action could be regarded as negligent. The court was not obliged to hold that a doctor was not liable for negligent treatment or diagnosis simply because evidence had been called from medical experts who genuinely believed that the doctor’s actions conformed with accepted medical practice. The reference in Bolam to a ‘responsible body of medical men’ meant that the court had to satisfy itself that the medical experts could point to a logical basis for the opinion they were supporting. This does not simply mean that the expert witness called for the defendant doctor has to be able to justify his views logically, but that the practice being defended must also be logically defensible. So, for example, assume that there are two surgical procedures for treating a particular condition, procedure A and procedure B. The literature has clearly shown that procedure B is much safer and more reliable than procedure A. Despite this, many doctors still use procedure A as it was the one which they were taught. A patient suffers injury as a result of undergoing procedure A. Under the Bolam test the doctor is not guilty of negligence as a responsible body would defend it. Applying the Bolitho test, however, the court might find that there was no logical basis for using procedure A and therefore the doctor was negligent.

ⒼBolam test A doctor is ‘not guilty of negligence if he has acted in accordance with a practice accepted as proper by a responsible body of medical men skilled in that particular art’.*

ⒽBolitho test If it had been demonstrated that the professional opinion defending the doctor’s action was incapable of withstanding logical analysis, the action could be regarded as negligent.

ⒾBreach of duty* Breach of a duty imposed on some person or body by a statute. The person or body is liable to any penalties imposed by such statute.

Equally, a first- year trainee doctor is not expected to have the same knowledge as his supervising consultant. The medical world is now full of guidelines and protocols, issued by the National Institute of Health and Care Excellence (NICE), by the Royal Colleges, by the GMC, by many hospitals, and by a host of other bodies. Failure to follow a guideline or protocol is not automatically negligent. However, where you are aware of a guideline or protocol and decide not to follow it, it would be wise to document your reasons for departing from it. Another practical way to protect oneself against an allegation of negligence is to seek a second opinion from a colleague, or discuss the patient’s case at a multidisciplinary team (MDT) meeting.

Causation

To succeed in a claim for damages, it is not enough for the patient to prove that the treating doctor has acted negligently; the patient must also prove that he or she has suffered some harm as a result of the negligence. For example, if a doctor accidentally prescribes the wrong dose of a drug, but this has no effect on the claimant’s treatment, there can be no claim for damages. Perhaps more surprisingly, if a poor outcome was more likely than not to occur, even if the treating doctor’s negligent actions have increased the risk of the poor outcome, the doctor is not liable. Imagine a patient who has suffered a serious leg injury. Even with appropriate treatment there is a 60% chance that amputation is required. The treating doctor provides negligent treatment, and an amputation becomes inevitable. The treating doctor is not liable for the amputation.

The claimant must prove on the balance of probabilities (i.e. more likely than not) that, as a result of the doctor’s action, or omission, he has suffered:

◘ a physical injury; and/ or

◘ an additional period of pain and suffering; and/ or

◘ a worse outcome than would have been the case with appropriate treatment; and/ or

◘ a psychiatric injury.

It can sometimes be very difficult to say whether the patient’s poor outcome or death was caused by his or her underlying condition or by negligent medical treatment. In a case where it is impossible to say whether or not the injury would have occurred but for the negligent act, it is sufficient for the claimant to prove that the contribution of the negligent cause was more than negligible.

If the patient suffers a psychiatric injury as a result of a physical injury (or poor outcome) or because of fear that he or she might suffer a physical injury, then the normal rules apply. However, if the claimant suffers a psychiatric injury as a result of the death or injury of someone else then special rules apply. To recover damages, the claimant must prove:

✦ Close ties of love and affection with the primary victim (usually a marital or parental relationship is required).

✦ The psychiatric injury occurred as a result of a sudden and unexpected shock to the claimant’s nervous system.

✦ The claimant was either personally present at the scene of the incident/ injury or was in the immediate vicinity and witnessed the aftermath.

✦ The psychiatric injury was caused by witnessing the death of, extreme danger to, or injury and discomfort suffered by the primary victim.

Contributory Negligence

In theory, the same principle applies to claims for clinical negligence. In practice it is very rare for allegations of contributory negligence to be made against patients. However, in a case where the patient’s outcome has been made worse by a failure, for example, to take his medication, to cooperate with medical treatment, or to attend medical appointments, it is certainly arguable that damages should be reduced.

Indemnity

National Health Service (NHS) indemnity provides legal cover for hospital doctors where they are caring for NHS patients but private insurance is required to cover non- NHS patients. NHS indemnity does not cover general practitioners (GPs). Claims in primary care are often brought against the clinician rather than the NHS.

Indemnity Insurance

Three categories of clinicians need to be considered, NHS employees undertaking NHS work, clinicians employed in the private sector, and everyone else.

NHS Employees

NHS employees who are acting in the course of their employment will be covered by NHS indemnity. This means that if someone wants to bring a claim for clinical negligence in respect of something they have done, the claim will be brought against their NHS employer rather than against them personally. The claim will be handled by the NHS, and (perhaps most importantly) any legal costs or damages will be paid by the NHS. In England, such claims are handled by NHS Resolution (in conjunction with the employer). There are equivalent organizations in Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland.

There are a few grey areas:

✧ Doctors undertaking waiting list initiative work in NHS hospitals for which they bill the NHS privately— NHS indemnity will apply.

✧ Doctors undertaking waiting list initiative work in private hospitals for which they bill the NHS privately— NHS indemnity will usually apply.

✧ Doctors undertaking clinical trials on NHS patients in NHS hospitals— NHS indemnity will usually apply even if the research is funded by a non- NHS body.

NHS indemnity does not apply to:

❖ Private work undertaken by the doctor.

❖ Some clinical trials.

❖ Work for voluntary or charitable bodies.

❖ Work overseas.

It follows that, if you are a clinician working solely as an employee within the NHS, there is no need for you to organize your own insurance. Despite this, most employed doctors choose to have limited cover with one of the medical defence unions. If no private work is undertaken the cost is relatively low. The advantage for the doctor is that if he or she ever needs legal advice this can be obtained for free.

Employees in the Private Sector

Clinicians working in private hospitals or clinics will either be employees or independent contractors (i.e. not on the payroll but submitting invoices either to the hospital or the patient for their work). Most doctors working in the private sector work as independent contractors (i.e. not employees); however, some clinicians (e.g. nurses, physiotherapists, etc.) are employed by the hospital or clinic. Such employees are in the same position as NHS employees. In the event of a claim arising from their negligence in the performance of their duties, their employer will be vicariously liable for the claim. In the circumstances the claim will again be brought against the hospital or clinic, rather than against the clinician personally. The hospital’s insurers will deal with the claim and be responsible for any legal costs or damages. So again, there is no need for such an employee to have their own insurance.

Criminal Liability

We are not concerned here with what may be termed deliberate criminal acts (e.g. stealing money or equipment from the NHS, punching a patient in the face, setting fire to the hospital, etc.). Rather, the question is whether a doctor simply undertaking medical treatment, with no intention to cause harm, can be criminally liable for his or her conduct? The answer is yes, but only in exceptional circumstances. If a patient dies as a result of medical treatment that was ‘grossly negligent’ the doctor may be found guilty of manslaughter. This is an offence that carries a maximum sentence of life imprisonment. In R v Adomako (1994) 3 All ER 79, the House of Lords set out the requirements for this offence:

★ A duty of care must be owed to the deceased (note: where a clinician is appointed to take charge of a patient they owe the patient a duty of care; however, simply being a doctor or nurse in a hospital will not necessarily mean there is a duty of care to a specific patient).

★ There must be a breach of that duty of care, which causes (or significantly contributes to) the death of the victim.

★ The breach should be characterized as gross negligence, and therefore a crime.

It is the last of these requirements that causes the most difficulty.

Sadly, many patients die each year as a result or inadequate or negligent medical treatment. The question is, how bad does that treatment need to be before it can be characterized as ‘grossly negligent’? Ultimately this is a matter for a jury to decide. The conduct must go beyond simple carelessness and be regarded as reprehensible. However, there is no clear test, and it is hoped that juries will simply know it when they see it. The following are some illustrative cases.

Cases of Criminal Liability

R v Prentice & Sullman

Doctors Prentice & Sullman were junior doctors at Peterborough Hospital. Malcolm Savage was a 16- year- old patient who was suffering from leukaemia. He attended the hospital for injections of cytotoxic drugs. Once a month he required intravenous injections of vincristine and every other month he required intrathecal (i.e. into the spine) injections of methotrexate. In February 1990 he attended for both drugs to be administered. Dr Sullman was a house officer. He had undertaken a lumbar puncture only once previously, and it had been unsuccessful. Dr Prentice was a pre-registration house officer. He had never previously undertaken a lumbar puncture. Notwithstanding this lack of experience Dr Prentice was instructed to administer the drugs under Dr Sullman’s supervision. Dr Sullman handed Dr Prentice a syringe of vincristine without checking what the syringe contained. Dr Prentice injected the vincristine into Malcolm’s spine, with fatal results. Both doctors were convicted by a jury of gross negligence manslaughter, and sentenced to 9 months’ imprisonment suspended for 12 months. The convictions were quashed on appeal, largely on the grounds of their inexperience.

R v Adomako

A patient undergoing an operation died after his anaesthetist, Dr Adomako, failed to check that the oxygen supply remained connected to his endotracheal tube during retinal surgery, or to react to the consequent cessation of movements of breathing, or to the cessation of the ventilator’s indicators of oxygen delivery. Dr Adomako was an experienced doctor in his 40s, but not a consultant. Expert witnesses described his care as ‘abysmal’ and concluded that he had shown a gross dereliction of duty. He was convicted of gross negligence manslaughter and sentenced to 6 months’ imprisonment suspended for 1 year. His conviction was upheld on appeal.

R v Misra & Strivastava

In June 2000 Sean Phillips underwent surgery to repair his patella tendon at Southampton General Hospital. Unfortunately, he became infected with Staphylococcus aureus. The condition was untreated. There was a gradual build- up of poison within his body, which culminated in toxic shock syndrome from which he died on June 27. Drs Misra and Strivastava were senior house officers involved in Mr Phillips’ postoperative care during the period beginning on the evening of June 23 until the afternoon of June 25. Despite the fact that Mr Phillips was obviously very unwell during this period neither doctor took any steps to arrange investigations or treatment. Each was convicted of gross negligence manslaughter and sentenced to 18 months’ imprisonment suspended for 2 years. Their appeals were dismissed.

R v Sellu

Mr David Sellu was a 66- year- old general surgeon. One of his patients developed abdominal symptoms after routine orthopaedic surgery. Mr Sellu did not make the careful assessment of the patient on the following morning that was required. He failed to operate until 40 hours later, and did not go and see his patient. The patient, Mr Hughes, later died. Mr Sellu was convicted of manslaughter and sentenced to 2½ years’ imprisonment. The sentence was not suspended.

NHS Complaints and Referrals to the GMC

NHS Complaints

Patients are encouraged to resolve any complaint they may have informally with their treating doctor. In most cases this will be the quickest and easiest way both for the doctor and the patient to resolve an issue. However, this will only happen if the doctor is open to such an approach. If you are overly defensive, or simply come across as being unapproachable, then it is more likely the patient will go down the formal route. Under the NHS Constitution, all complaints by patients must be investigated and a response given. The complaint may be about a poor medical outcome, but it could be about many other things, such as:

○ a doctor’s manner;

○ a refusal to agree to a particular treatment;

○ a refusal to prescribe a particular drug;

○ the speed of treatment or referral.

The complaint may be made directly to the NHS trust, hospital, or practice who provided the treatment or, alternatively, to the clinical commissioning group (CCG) which commissioned it.

Referral to the GMC

A referral to the GMC is potentially the most serious consequence for a doctor following an unexpected clinical outcome. A referral can be made by anyone; however, it is usually one the following:

⇾ The aggrieved patient or their family.

⇾ The doctor’s employer.

⇾ Another doctor or other health professional.

⇾ The doctor’s Royal College or other professional body.

The GMC will not normally investigate complaints more than 5 years old. The GMC stresses that it deals with only the most serious complaints, and encourages aggrieved patients (at least in the first instance) to complain to the doctor’s local clinic or hospital employer. The GMC deals with a much wider range of complaints about doctors than clinical errors. The sort of cases that may be referred to them include:

⇢Serious or repeated mistakes in carrying out medical procedures or in diagnosis.

⇢Failing to examine a patient properly or to respond reasonably to a patient’s needs.

⇢Serious concerns about knowledge of the English language.

⇢Abuse of professional position (for example, an improper sexual or emotional relationship with a patient or someone close to them).

⇢ Discrimination against patients, colleagues, or anyone else.

⇢ Fraud or dishonesty.

⇢ Breach of patient confidentiality.

⇢ Violence, sexual assault, or indecency.

⇢ Any serious criminal offence.

If a complaint is made to the GMC it will decide (usually within 2 weeks) whether the complaint raises serious concerns about a doctor’s fitness to practise. If it does not no further action will be taken. If the GMC decides to investigate, the first step will be to write to the doctor to obtain his or her comments on the complaint. This may be the first time you become aware of the complaint, and you should immediately contact your medical defence organisation for help and advice on how to respond. The doctor’s comments will be sent to the complainant to give him or her an opportunity for further comment. The case will then be considered by two GMC case workers, one of whom will be medically qualified. They will do one of four things:

⊛ Close the case without taking any further action.

⊛ Issue a warning to the doctor.

⊛ Agree undertakings with the doctor to re- train or to work under supervision.

⊛ Refer the doctor to a medical practitioner’s tribunal service for a fitness to practise panel.

If there are immediate concerns that a doctor may pose a risk to patients, the doctor may be referred to an Interim Orders Panel, which can suspend or restrict the doctor’s practice while the investigation is ongoing. The fitness- to- practise panel will hold an oral hearing (at which the doctor may wish to be represented by a lawyer) to decide whether any action is required. The panel has a wide range of powers, including:

‣ Permanently erasing the doctor’s name from the medical register.

‣ Suspending the doctor from the register for a set period.

‣ Putting conditions on the doctor’s registration so that he or she is only allowed to do medical work under certain conditions or restricted to certain areas of practice.

(ps The cases for examples covered here are mostly from the UK/Europe as I have managed to get information and the latest updates on books originally from the UK if however I do stumble across any American sources with enough facts I will do an American version with the obvious references to the incidents and the court proceedings that have happened there! I’ve also sat down thinking about how to possibly illustrate such a vital topic in the medical sciences as this is something I think is needed to be included in an undergraduate level with an equal and an individualistic importance to each country in general! Ethics is a broad topic and is interesting and invest-worthy to cover! Much thanks to you guys for waiting patiently for each and every post!

There will be a continuation of the sub heading under this category! With future posts to come! Much love to you guys, my scriveners! ♡)

Sources:

• The Oxford Handbook of Medical Ethics and Law

• A Medic’s Guide to Essential Legal Matters

• Philosophical Foundations of Medical Law

• Sourcebook on Medical Law