The Most Recent Study in Nepal for Dengue Transmission

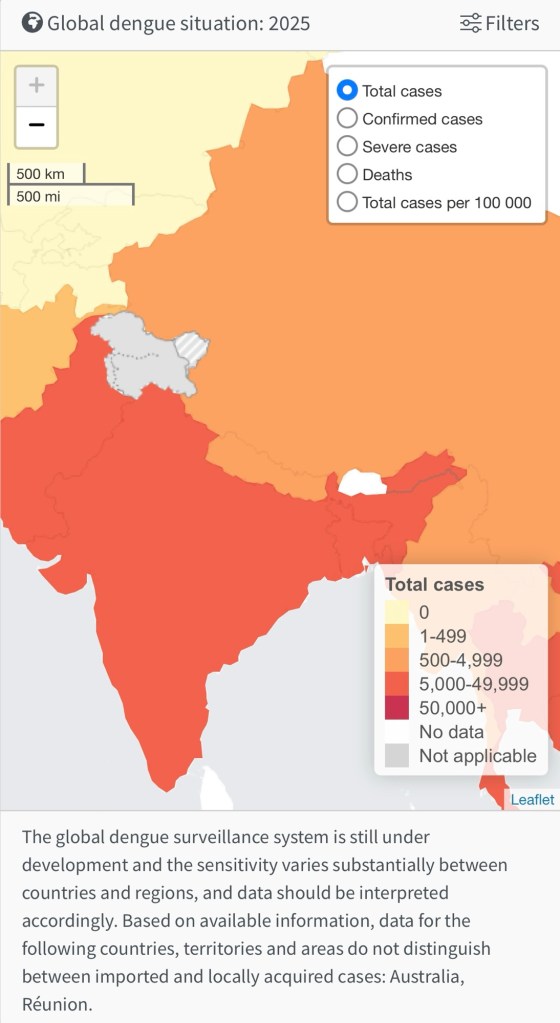

The geographical distribution of dengue in Nepal is gradually changing and spreading to all districts of Nepal [15,19,31]. A serotype switching phenomenon has been observed during major outbreaks in Nepal in recent years. For instance, outbreaks were primarily driven by DENV-1 and DENV-2 in 2010, followed by a predominance of DENV-2 in 2013. DENV-1 re-emerged in 2016, with DENV-2 becoming dominant again in 2017. In 2019, both DENV-2 and DENV-3 circulated, while the 2022 outbreak had a co-circulation of DENV-1 and DENV-3 [15,16,17,32,33]. The serotype distribution of the Terai or hilly or mountain regions may differ, e.g., DENV-2 was the major contributor in the 2023 outbreak in Dhading (hilly region), central Nepal [15], and Jhapa, eastern Nepal [34], while both DENV-1 and DENV-2 were key players in our study area, i.e.,Mahottari (Terai region) in southern Nepal.

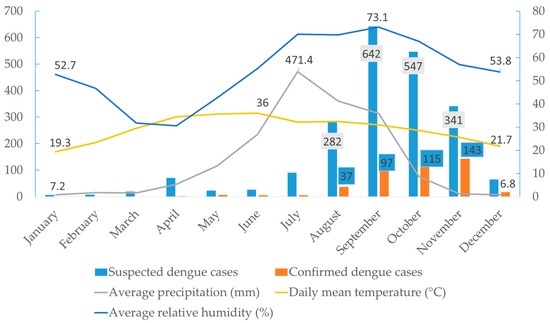

The observed gradual increase in dengue cases from June (n = 5) with a peak in November (n = 143) aligns closely with the seasonal patterns of temperature, relative humidity, and precipitation. The breeding, survival, and biting behaviour of Aedes mosquitoes are directly affected by these environmental factors. In Nepal, the monsoon season typically spans from June to September, characterised by high rainfall and humidity, creating ideal conditions for mosquito proliferation due to the abundance of water sources for breeding [35]. The high number of dengue cases in November (post-monsoon) is likely due to the incubation period of the virus in both the vector and human host [36]. Similar seasonal trends have also been reported in other South Asian countries, where vector density and dengue incidence typically rise post-monsoon [37]. Further, the lack of proper waste management, inadequate public awareness, abundance of discarded tires with stagnant water, and poor sanitation facilities in this area create a favourable breeding environment for vectors. The influence of additional factors, such as urbanisation, increased mobility, and higher adaptability of Aedes spp. on virus dissemination, cannot be ruled out despite the emergence of new serotypes. Bardibas, Mahottari, is a growing town and transit hub of national highways connecting Terai to Kathmandu, the capital city of Nepal [24]. Moreover, due to open borders, Bardibas receives a large influx of people from the neighbouring dengue-endemic state of India (Bihar), which provides ample opportunity for DENV transmission [38]. Therefore, timely interventions of vector control measures before and during the monsoon season can help to mitigate the surge in dengue cases in the region.

Bilirubin levels were significantly higher in patients with secondary dengue compared to primary, but the increment in liver enzymes did not reach statistical significance. This suggests an increased hepatic involvement in secondary dengue due to a more pronounced immune response being caused [50]. Interestingly, the blood parameters between inpatients and outpatients were not different. This might be because of public panic behaviours seen after dengue infection, which led to increased insistence on admission regardless of the severity levels. This is even more common in peripheral/community hospital settings like ours [15]. Increased public awareness and improving clinician compliance to national dengue management guidelines with adequate training will help in coping with situations like this.

In 2023, we confirmed more than 400 dengue cases in Bardibas alone, while the EDCD reported less than 100 cases [19]. This underscores a huge opportunity for improving dengue early warning and reporting systems and strengthening the national database. Efforts from the government/EDCD in combating dengue have notably enhanced over the past few years. However, existing gaps in the surveillance and reporting system should be addressed to enable more accurate disease burden estimation and facilitate evidence-based policy and strategy formulation. Dengue virus genomic surveillance is essential for monitoring the emergence and spread of different serotypes and genotypes, detecting mutations that may affect virus transmissibility or virulence, guiding vaccine development and effectiveness, and initiating timely public health interventions to control outbreaks and reduce disease burden.

Aedes Characterisation & Lifecycle

A. aegypti has been incriminated as the principal vector which is primarily an urban mosquito but sometimes it is also found in the periphery of cities breeding in rain water accumulated in tree holes. The virus has also been isolated from Ae. albopictus. This species is mainly urban and semi-urban, breeding in domestic and peridomestic water storage containers.

Dengue is a viral infection transmitted to humans through the bite of infected mosquitoes and is found in tropical and sub-tropical climates worldwide, mostly in urban and semi-urban areas. The primary vectors that transmit the disease are Aedes aegypti mosquitoes and, to a lesser extent, Aedes albopictus.

Dengue virus (DENV) has four serotypes (DENV-1, DENV-2, DENV-3, DENV-4) and it is possible to be infected by each. Infection with one serotype provides long-term immunity to the homologous serotype but not to the other serotypes; sequential infections put people at greater risk for severe dengue. Many DENV infections produce only mild illness; over 80% of cases are asymptomatic. DENV can cause an acute flu-like illness.

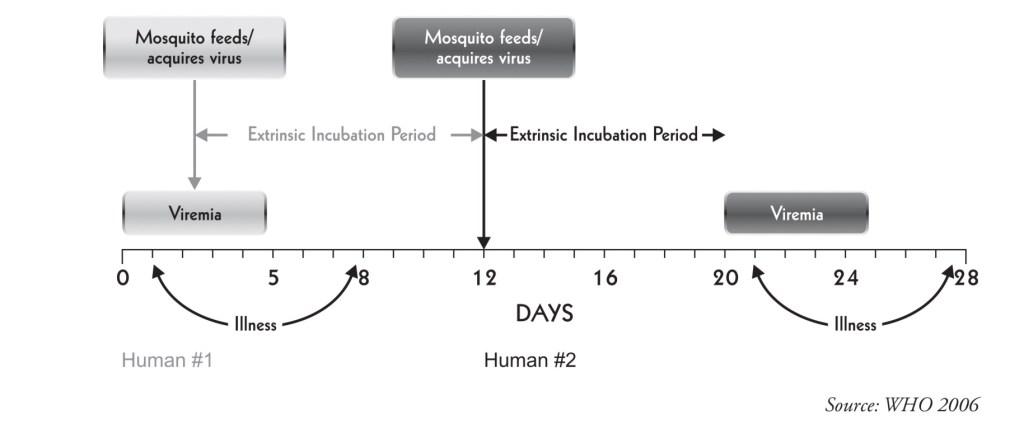

The reservoir of infection is both man and mosquito. The transmission cycle is “Man-mosquito-man”. A. aegypri is the main vector. The Aedes mosquito becomes infective by feeding on a patient from the day before onset to the 5* day (viraemia stage) of illness.

After an extrinsic incubation period of 8 to 10 days, the mosquito becomes infective, and is able to transmit the infection. Once the mosquito becomes infective, it remains so for life.

Transovarian transmission of dengue virus has been demonstrated in the laboratory.

In Nepal, the first dengue infection was reported in a Japanese volunteer working in the southern part of the country in 2004 [13]. The first endogenous outbreak was recorded in 2006, after which Nepal experienced major dengue outbreaks in 2010, 2013, 2016, 2019, 2022, and 2023 [14,15,16,17,18]. Despite this, fatalities due to dengue remained very low in Nepal. However, following the 2022 dengue epidemic, with over 54,000 cases and 88 deaths, another unprecedented outbreak unfolded in 2023, recording over 51,000 cases and 20 deaths in Nepal [14,19]. Additionally, in 2024, 34,385 dengue cases, along with 13 fatalities, were reported [20].

Signing off,

Nivea Vaz

Campaign Ambassador for Dengue Search & Destroy

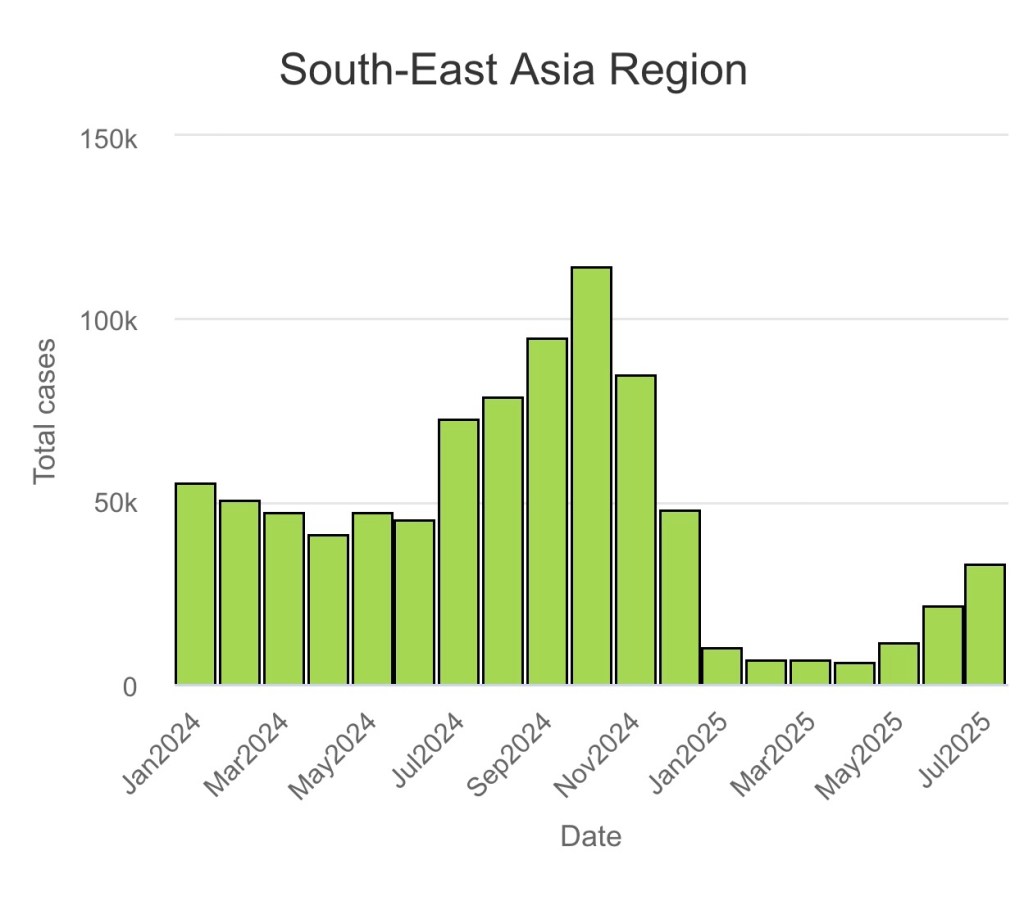

(Unfortunately, there has not been any data released so far from Jan 2025 to July 2025 by the government/EDCD. So I will have to update this post at some point but I don’t know when, the WHO global databases does not include Nepal completely in the South Asia Region bar graphs!Its also not as coherent as to how much data has been collected as of 2025!♡)

Sources:

https://www.who.int/emergencies/disease-outbreak-news/item/2022-DON412

https://www.mdpi.com/2076-0817/14/7/639

https://worldhealthorg.shinyapps.io/dengue_global/