An old Cherokee man was teaching his grandson about life. As the embers from their campfire floated up into the night sky, the old man said,

‘Grandson, there is a fight going on inside me. It is a terrible fight between two wolves. One wolf is evil. He is anger, envy, sorrow, resentment, and regret. He is greed, arrogance, self-pity, and ego. The other is good. He is joy, peace, love, hope, serenity, humility, and kindness. He is empathy, generosity, truth, compassion, and faith. This same fight is going on inside you, and in every other person, too.’

The grandson thought about it for a minute, and then asked, ‘Which wolf will win?’

The old man simply replied, ‘The one you feed.’

This traditional Cherokee tale, whose origins are unknown, speaks of the dual nature of man – primal and impulsive, while simultaneously rational and logical. That dual nature has long been a focus of inquiry for philosophers, theologians, artists and writers, all of them exploring the checks and balances that keep us centred and speculating on what happens when that primal, animal nature becomes dominant.

The werewolf is probably the most well-known shapeshifter and is the quintessential example of what can go wrong when that animal nature takes control. Its popularity and attraction may say something about our own latent desires to be free of the shackles of morality and social mores and to run naked through the night-time woods, howling at the Moon. At the very least, the popularity of the werewolf in folktales, movies and books is a testament to our fascination with the forbidden, animal side of our nature.

In the 1760s, villagers in the remote, mountainous region of Gévadaun in southern France suffered attacks from a huge, wolf like beast. Beginning on 15 January 1765, with the horrible death and mutilation of a young girl, and ending in 1767 with the killing of the ‘Beast of Gévadaun’, as it became known, the creature savagely slaughtered at least a hundred people, mostly women and children, in a wave of terror that was called the ‘time of the death’. According to eyewitnesses, the Beast was hairy, black or reddish-brown in colour, with sharp teeth, a powerful tail and an unpleasant odour. It could run at great speed and leap to incredible heights. The Beast showed no fear of humans and attacked individuals or groups with equal ferocity, literally tearing its victims limb from limb with its sharp claws, disembowelling them with its razor-sharp teeth.

The people of Gévadaun lived in constant terror, as the Beast wandered from village to village; entire villages would empty out when the Beast was reported to be in the vicinity. The situation became so dire that King Louis xv dispatched a detachment of dragoons to the area to hunt down the Beast. They were unsuccessful, but the king also sent a huntsman named François Antoine to kill the Beast. On 21st September 1765 Antoine shot and killed a large grey wolf weighing 60 kilograms (132 lb). He stuffed the animal and sent it to the king, who displayed it in the palace at Versailles. Unfortunately, the stuffed wolf was not the Beast. Two months later, the horrific killings resumed.

In 1767 the Beast was finally tracked down and killed by Jean Chastel, a local hunter. Chastel’s own testimony states that he shot the Beast using silver bullets blessed by a priest, a traditional way of killing a werewolf.

So what was the Beast of Gévadaun? Some theorize that the creature was a hybrid animal, perhaps the offspring of a wolf and lion, or wolf and hyena. Some say it might have been a leopard. Some of the villagers in Catholic France believed the Beast to be the Devil incarnate. But others were certain the Beast was a werewolf. They cited eyewitness accounts of the Beast standing and running on two legs. Chastel described the dead Beast as having ‘peculiar’ feet, coarse, dark hair, and pointed ears. The members of the hunting party that accompanied him all described the Beast as half-man and half-wolf, a true werewolf. Werewolf or not, the Beast’s grisly legacy lives on in Gévadaun, where there are several monuments to the Beast, and in the village of Saugues, home to an entire museum devoted to the Beast and its three-year reign of terror.

It may seem strange to us to think that entire populations would be convinced a werewolf stalked them, but shapeshifters of all kinds seemed real in the eighteenth century, just as they had for centuries before. Why wouldn’t werewolves seem real when there was a long history of people who readily confessed to being one?

The traditional werewolf, or lycanthrope, is a person who changes into a wolf at the full moon. In Greek mythology, Lycaon is transformed into a wolf as a punishment, meted out by Zeus for the man’s cannibalism, but in the Middle Ages, when werewolf tales were abundant, most of the transformations occurred spontaneously. Many of the tales speak of werewolves simply as supernatural beings, rather than people transformed against their will by higher powers. Sometimes the assumption is made that a werewolf transformation is the result of a curse, although the nature of the curse and its origin are not often clear.

In any case, the idea of lycanthropy has been around for a long time. It was known to the ancient Romans as versipellis, that is, ‘skin changer’, or ‘turn skin’. Paulus Aegineta, a seventh-century Byzantine Greek physician, wrote in his Medical Compendium in Seven Books that lycanthropy was neither self-induced nor a welcome change to the sufferer but was, in fact, a mental disease caused by brain malfunction, humoral pathology and hallucinogenic drugs.

Lycanthropy is a rare psychosis in which the patient has delusions of being a wild animal, usually a wolf.

Harold M. Young, a British bureaucrat serving in Burma (now Myanmar), spent much time among the Shan people, where he heard tales of a werewolf-like creature called taw. In 1960 he had a weird encounter with one. As told in Christopher Dane’s book The Occult in the Orient, Young was visiting a Shan village one moonlit evening, when he heard strange noises coming from a hut. He cautiously approached the hut and peered in through a window:

Inside the hut was a ghastly creature, chewing slowly on the slashed neck of a dying woman. The hideous beast could only be described as half-human, half-beast. Its body was covered with coarse hair. Its face was grotesque; its eyes small and red. Its mouth showed cruel fangs, dropping blood and spittle as it worked deeper into the woman’s flesh.

Young fired his pistol at the beast, which leapt up and ran into the jungle. Young and the villagers gave chase but lost the beast in the dense foliage. They resumed the search in the morning and picked up a trail of blood, which circled back to the village and led to a hut. Bursting into the hut, the men found a dead man lying there, a bullet wound in his side. One of the villagers spat on the corpse, uttering the single word, taw, meaning ‘shapeshifter’.4

Werewolf sightings have been reported all around the world, creating an international treasure trove of werewolf lore. Here is a partial list of countries with their associated werewolves:

Argentina – the lobizón, a fox-like werewolf

Bulgaria – the vrkolak, a werewolf that turns into a vampire after death

China – the lang ren

France – the loup-garou

Iceland – the varulfur

Italy – the lupo mannaro

Latvia – the vilkacis, whose name means ‘wolf eyes’

Mexico – the nahual can turn into a wolf, large cat, eagle or bull

Norway and Sweden – the cigi einhamir transforms by wearing a wolfskin

Philippines – the aswang is a vampire-werewolf

Portugal – the lobh omen is the typical werewolf, but there is also the bruxsa, a vampire-werewolf

Russia – the bodark

Serbia – the wurdalak is a werewolf that has died and become a vampire

Slovakia – the vlkodlak is a werewolf that has been transformed through sorcery

Spain – the lobo hombre

In a study called ‘The Moon and Madness Reconsidered’, they proposed that before the advent of effective artificial lighting in the nineteenth century, the full moon probably did affect those with precarious mental health, by disturbing quality and duration of sleep. They cited evidence that resting in the dark for fourteen hours a day can terminate or even prevent episodes of manic psychosis, and that even a mild reduction in hours of sleep can worsen mental health and bring on epileptic seizures – something my own patients with bipolar illness and epilepsy have confirmed. Patterns of activity in the brain involved in healthy sleep seem to overlap with patterns associated with good mental health in ways we don’t yet fully understand.

But moonlight was also shadowy enough to give a prompt to the fearful imagination. ‘The insane are more agitated at the full of the moon, as they are also at early dawn,’ the French psychiatrist Jean-Étienne Esquirol wrote in the nineteenth century: ‘Does not this brightness produce, in their habitations, an effect of light, which frightens one, rejoices another, and agitates all?’

JOANNE FREDERICK was brought in by ambulance; ‘agitated delirium’ was written across the top of her triage sheet. The medical history came from her flatmate: she’d been suffering with a head cold for a few days, feeling weak and under the weather, and had gone to the pharmacy to buy medicine. It didn’t work: she became weaker, had abdominal pains, and her skin felt as if it was burning. Her urine felt hot and heavy, and was painful to pass. She’d had urine infections in the past, but this was different: a bodily unease had possessed her, spreading up through her torso and out into her limbs. Her legs trembled, her arms lost all their power, and she had a persistent low-grade fever. She arranged an appointment to see her GP, but never made it: her flatmate called an ambulance when she began hallucinating giant lizards on the walls. On the way to hospital in the ambulance she had a seizure and when I met her in the high-dependency unit, she had been sedated.

There are hundreds of reasons that someone might end up with an ‘agitated delirium’: drug overdoses, drug withdrawal, infections, strokes, brain haemorrhage, head injuries, psychiatric disorders, and even some vitamin deficiencies. But all of Joanne’s blood tests came back normal – the CT scan of her brain was unremarkable. As she lay sedated in the high-dependency unit, her flatmate began to tell me more of her story. Joanne lived a fairly quiet life, with a few close friends but keeping largely to herself. She’d been admitted to hospital with a ‘nervous breakdown’ once before; the hospital notes said that she’d had a brief episode of incapacitating panic and anxiety that had resolved after a few days’ rest. She worked as an administrator in the basement of the city council offices – a job she loved because it allowed her to stay out of the sun. ‘She burns really easily,’ said her flatmate, ‘you should see her in the summer – she gets blisters from it.’ Her skin was mottled with brown pigments, particularly across the face and hands, as if coffee granules had been spilled over wet skin.

I was a junior doctor at the time, and for me and the rest of the medical team Joanne’s diagnosis was a puzzle. When the supervising physician arrived to do his rounds he listened carefully to the story of how Joanne had come to be there, and flicked through the hospital notes from her previous admission. He examined her skin closely, leafed through the reams of normal tests, then looked up with a glance of triumph: ‘… we need to check her porphyrins,’ he said.

Porphyrins, critical for both the structure of haemoglobin and chlorophyll, are generated in the body by a series of specialised enzymes that work together like a team of scaffolders. If one of those scaffolders doesn’t work properly, porphyria is the result. Part-formed rings of porphyrin build up in the blood and tissues bringing on ‘crises’, which can be occasioned by drugs, diet, and even a couple of nights of insomnia. Some porphyrins are exquisitely sensitive to light (it’s this property that enables them to absorb the sun’s energy in chlorophyll) and some types of porphyria lead to a blistering inflammation on exposure to the sun, with consequent scarring. The build-up of porphyrins in nerves and the brain causes numbness, paralysis, psychosis and seizures. Another effect of the accumulation of porphyrins in the skin, as yet unexplained, is growth of hair on the forehead and cheeks. Acute porphyria can cause constipation and agonising abdominal pain: it’s not unusual for victims to be brought howling into operating theatres, subjected to unnecessary operations time and again before doctors reach the correct diagnosis.*

When Joanne’s lab report came back it confirmed soaring levels of porphyrins: it was likely that she had a rare variant of porphyria known as ‘variegate’. Treatment had already begun: rest, avoidance of exacerbating drugs (the cold remedies she’d bought over the counter had probably triggered her crisis) and intravenous fluids. To those we added infusions of glucose. Within three days she had recovered, and was discharged home from the ward with a list of drugs to avoid and an explanation, at last, of why she’d always been sensitive to light.

IN 1964 A CURIOUS PAPER was published in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society of Medicine by a London neurologist called Lee Illis. In four eloquent and persuasive pages he proposed that the myth of werewolves has been reinforced or even initiated by porphyria. Skin conditions such as hypertrichosis may cause hair to grow over the face and hands, but have no psychiatric manifestations.

Illis pointed out that people with porphyria avoid direct sunlight, and prefer to go about at night. Crises are precipitated by periods of poor sleep or a change in diet. In severe untreated cases sufferers may have pale, yellowish skin caused by jaundice, scarring of the skin, and hair may even begin to grow across their faces. People with certain types of porphyria may suffer derangements in their mental health and become socially isolated, breeding distrust among the wider community.

Conceptualising Psychotic Disorders…

Growing evidence suggests that complex spectra of psychotic disorders are related to a large number of phenotypes associated with heterogeneous gene networks and environmental risk factors affecting diverse pathophysiological processes. However, the diagnostic concept of psychotic disorders remains largely as it was originally constructed over a century ago. Most of the criteria defining psychotic disorders continue to be based on clinicians’ interpretation of the subjective reports of symptoms by patients. There continues to be uncertainty on what is precisely the core disturbance underlying schizophrenia and related psychotic disorders; the nature of the boundaries of this spectrum and those of the syndromes within the psychotic spectrum also remain a topic of debate.

THE CATATONIA CONUNDRUM

A significant limitation in the definition of psychotic disorders has been the variable definitions of catatonia and its discrepant treatment across the manual (e.g., subtype of schizophrenia but a specifier of mood disorders). 43,44 It is widely known that catatonia occurs across a variety of disorders, including schizophrenia, bipolar disorder and depression, and can also be secondary to general medical conditions. In DSM-5, a single definition of catatonia is used and catatonia is treated as a specifier across all conditions.

Catatonia not otherwise specified is added as a residual category to allow for the rapid diagnosis and specific treatment of catatonic symptoms in severely ill patients in whom the underlying diagnosis is not clear.

KEEPING PACE WITH CHANGE: DSM AS A LIVING DOCUMENT

Continuing flexibility for the classificatory systems is critical for keeping pace with the rapid conceptual changes and accumulation of knowledge in psychiatric disorders. Unlike previous editions of the DSM, DSM-5 has been designed as a “living document’ with the provision for periodic updates (versions 5.1, 5.2, etc.)3 and it is likely that the scale for measurement of the six psychotic dimensions will be elevated to the main body of the manual. Updates will also be made based on clinician feedback and new research findings. While DSM-S has advanced the nosology of schizophrenia, the next section explores continuing challenges and future directions for the conceptualization and definition of schizophrenia.

THE VARIOUS MEANINGS OF ‘UNITARY PSYCHOSIS’

When the central and attending concepts briefly analyzed here are put together, it becomes apparent that the concept of “unitary psychosis” is multi-vocal. What determines which meaning is current or fashionable within each historical period is unclear. It is likely, however, that it will depend less on the advances of science than on their temporal economic and social value.

ILLUSTRATIONS FROM ITS HISTORY

The question of whether “madness” (insanity, lunacy, distraction, folie, Wahnsinn, Pazzia, locura, etc.) referred to one or various disturbances of behavior (e.g., lycanthropy, dementia, vesania, melancholia, fury, frenzy, mania, etc.) was already debated before the 19th century.86 At the time, this was not known as the “unitary psychosis” problem, for neither of these concepts was available to the interested parties. Since the publication of “Unitary Psychosis: A conceptual history,”87 efforts have been made to resolve the problem “empirically” by subjecting important clinical and genetic information to serious statistical analysis.88 The fact that the problem has not yet been resolved suggests that its nature is conceptual rather than empirical. There is space in what follows only to describe two historical episodes illustrating unitarian views related to the bottom and the top layer.

PSYCHOTIC SYMPTOMS ACROSS TRADITIONAL DIAGNOSTIC CATEGORIES

Evidence from experimental, psychopathological, neurobiological, and genetic studies indicate overlapping symptoms, treatments, outcomes, and biological and genetic markers between psychotic disorder categories, suggesting a multidimensional spectrum encompassing nonaffective and affective psychosis. Clinical research indicates that bipolar disorder and schizophrenia can be usefully conceptualized as the distant ends of a multidimensional severity continuum, in which schizoaffective disorder lies at the midpoint.” Both core positive symptoms of nonaffective psychotic disorders (delusions and hallucinations) and negative symptoms cross diagnostic categories. 2,13 Reversely, there is remarkable variation in pre-morbid course, symptom profile, treatment and outcome of patients diagnosed with the same categorical diagnosis. l4,15 Several psychometric studies have revealed that the spectrum of major psychotic disorders might be modelled using five main symptom dimensions: mania, positive symptoms, disorganization, depression, and negative symptoms. 16-18 To determine the organizational structure of symptom dimensions at onset and its concordance with categorical diagnoses, Russo and colleagues cross-sectionally analysed data of 500 patients with first episode psychosis. Factor analyses revealed six first order symptom dimensions including mania, negative, disorganization, depression, hallucinations, and delusions and also two higher order factors as affective and nonaffec-tive psychoses. In a follow-up longitudinal design, they examined the stability of the organizational structure of symptom dimensions after 5 to 10 years of follow-up among 100 of these patients, and showed that the factorial structure of symptoms during the first episode remained stable over the follow-up period. Recent symptom-focused studies indicate a bifactor model, encompassing both a general dimension as well as five symptom dimensions (positive and negative symptoms, mania, depression, and disorganization).20-23

Clinical relevance

Arguably the most important argument for a dimensional conceptualization is that research shows that dimensions have added clinical value over and above a categorical representation. Thus, dimensional “diagnosis” allows for a flexible, personalized, and dynamic way of charting a patient’s symptoms as depicted in Fig. 3.1,2.36 which has advantages over static categories that do not accurately convey personal psychopathology and cannot capture changes over time. Also, research indicates that dimensional information predicts course and outcome over and above the information conveyed by categorical diagnosis, which has to do with specific predictive associations of dimensions with onset, course, and other correlates, as summarized in Fig. 3.1.37-40

Psychotic Psychopathology Across Clinical and Non Clinical Populations

Clinical relevance

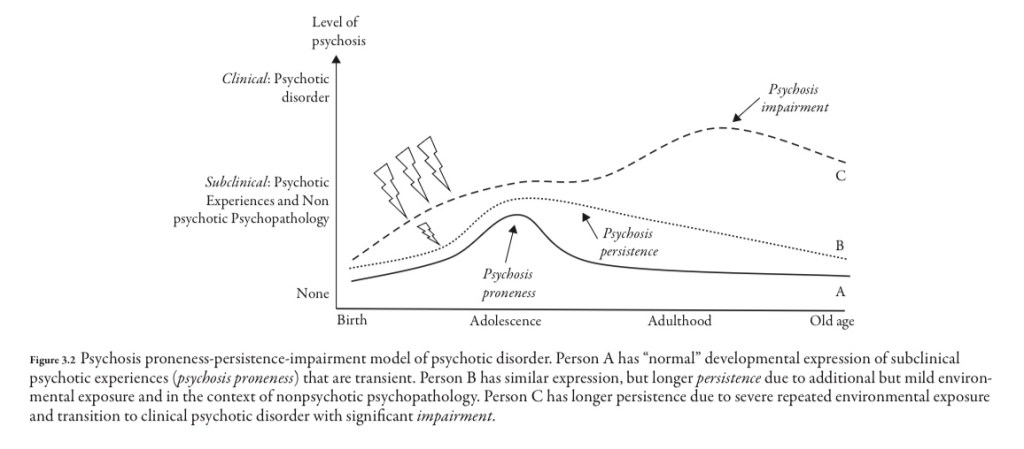

The occurrence and course of psychotic experiences can be summarized within a developmental framework as embedded in the psychosis proneness- persistence- impairment model, depicted in Fig. 3.2. Psychosis proneness represents distributed genetic and non genetic risk in the general population, associated with a degree of subthreshold expression of psychosis which, with increasing levels of developmental environmental exposure, takes on clinical relevance in, first, expression of psychotic experiences and multidimensional psychopathology at the level of non psychotic disorders and, finally, transition to full- blown psychotic disorder.

The psychosis proneness-persistence-impairment model implies an underlying mechanism of gene-environment interaction between distributed polygenic risk and developmental environmental exposures. This model was examined recently in a large 25-country study, funded by the European Union (EUGEI study”). The results showed independent and joint effects of molecular genetic liability (polygenic risk for schizo-phrenia) and environmental exposures (cannabis, childhood adversity) in psychosis spectrum disorder, confirming the hypothesis.

A DIMENSIONAL PSYCHOSIS SPECTRUM SYNDROME: CURRENT APPROACHES

Taken together, clinical, genetic, epidemiological, and neurobiological findings indicate that there is overlap between mood and psychotic disorders, and overlap between clinical and nonclinical expressions of psychosis-associated psycho-pathology, challenging the classical categorization of major psychotic disorders represented in current diagnostic systems such as DSM and ICD. A spectrum approach in psychosis may be more productive.

On Further Reading:

https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/070674377502000706

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/pcn.13177

It is one of the most underrated psychiatric conditions!

Sources:

- SHAPESHIFTERS: On Medicine & Human Change-Gavin Francis

- SHAPESHIFTERS A History- John B Kachuba

- Psychotic Disorders, Comprehensive Conceptualisation and Treatments

(Whew! This was a heavy edit! Hope you enjoyed the Halloween edit! Happy Halloween in advance!)🎃