In the course of ethical debate about abortion, a discussant may pose a question such as: is it morally permissible to abort a foetus of twenty- eight weeks’ gestation because the pregnant woman has suffered a breakdown of her spousal relationship? Or perhaps she may ask whether it is more or less ethical for a pregnant woman to abort a foetus of twenty- eight weeks’ gestation because it is discovered to have a cleft lip palate, and what is the relevant moral difference between the two cases, if there is one. She may ask what difference it would make to our answers in both cases if the foetus were not twenty- eight weeks gestated, but twelve weeks, or if the woman concerned were extraordinarily rich, or particularly poor.

Introduction

It is, of course, hardly correct to speak of ‘feminism’ as if it denotes a unified theory. There is no single feminist theory, but rather many kinds of feminisms, loosely bound together. Still, assuming that there is some common thread which links all feminisms to one another, it is sensible to ask what that thread is. Janet Halley has attempted to capture it by offering two essential components of feminist thought. The first is the descriptive claim that makes some distinction between M and F (whether this be ‘man’ and ‘woman’, ‘male’ and ‘female’, or ‘masculine’ and ‘feminine’) and posits that F is disadvantaged relative to, and subordinated by, M. The second is the evaluative claim that F’s subordination is unjust and ought to be resisted. ‘Feminism is feminism because’, she says, ‘as between M and F, it carries a brief for F’. As far as feminism is identified only with these two core claims, the complaint against traditional moral philosophy cannot be ascribed to all feminists.

One important aspect is the idea that mainstream ethical theory, carried out in what Sherwin calls ‘the masculine voice’, crowds out a more quintessentially feminine approach to ethical dilemmas, which looks to the unique features of each case and the possibilities for interpersonal resolution. On this point, Sherwin refers to the well- known work by the psychologist Carol Gilligan, who conducted experiments to observe the different tendencies of women as compared with men when reasoning about ethical problems. In Gilligan’s experiments, separate groups of female and male subjects were presented with identical ethical dilemmas, being asked, for example, whether it would be morally permissible for an impoverished person to steal medicine from a chemist to save the life of her sick child. Gilligan found that whereas the men argued with one another about abstract principles such as the immorality of theft and the sanctity of human life, the women tended to ask further questions about the particular scenario, such as: ‘Why doesn’t the parent just ask the chemist to give her the medicine she needs?’

Gilligan’s conclusions, in Sherwin’s words, were that:

female subjects tried to preserve relationships and to find new options through better communication and a presumption of co- operation; they tended to respond by seeking more information, or by trying to reconceive the terms set by the example.

While the women were especially interested in the ‘particular narrative details’ and ‘specific human dynamics’ of a situation, the men were, instead, ‘preoccupied with developing comprehensive, generalizable, abstract ethical systems which are based on rights’.

Broadly speaking, ‘abortion’ denotes the practice of terminating a pregnancy in such a way as to destroy the life of the foetus being carried by the pregnant woman. In the case of abortions carried out early in pregnancy on non- viable foetuses, the fact that the foetus is expelled from the womb is sufficient for its death. In other cases, where the foetus is more mature (and capable of surviving outside the womb), additional steps will be taken to ensure that it dies prior to delivery. Either way, it is apparent that the practice stands in direct opposition to the major forms of fertility treatment considered that is assisted reproductive technologies. There the intention is normally to produce a pregnancy resulting in a successful live birth. Here, the intention is to bring an existing pregnancy to an end without the birth of the child. In another sense, however, there is a close relationship between the practices in that they both implicate (albeit in opposing ways) reproductive freedom.

Robertson, JA, Children of Choice, 1994, Ewing, NJ: Princeton UP, p 26:

An essential distinction is between the freedom to avoid reproduction and the freedom to reproduce. When people talk of reproductive rights, they usually have one or the other aspect in mind. Because different interests and justifications underlie each, and countervailing interests for limiting each aspect vary, recognition of one aspect does not necessarily mean that the other will also be respected; nor does limitation of one mean that the other can also be denied. However, there is a mirroring or reciprocal relationship here. Denial of one type of reproductive liberty necessarily implicates the other. If a woman is not able to avoid reproduction through contraception or abortion, she may end up reproducing, with all the burdens that unwanted reproduction entails. Similarly, if one is denied the liberty to reproduce … one is forced to avoid reproduction, thus experiencing the loss that absence of progeny brings. By extending reproductive options, new reproductive technologies present challenges to both aspects of procreative choice.

Gillian Douglas has explored the background to the right to avoid reproduction claimed for individuals as follows:

Douglas, G, Law, Fertility and Reproduction, 1991, London: Sweet & Maxwell, p15:

“….To what extent have individuals been at liberty to make use of these? The former, certainly, have always been forthrightly condemned by the Roman Catholic Church, drawing originally upon the Jewish view that the duty to procreate through marriage is the first of all commandments. Sex became associated by St Augustine with sin, and could only be justified by procreation. Aquinas considered that to dissociate sex from procreation was to act against nature and therefore to sin. The breaking down of this religious influence and the rise of a rights-based political philosophy in the West during the 18th and 19th centuries, utilised first by men and then by women, enabled individuals to challenge these old ideas and control of sexual behaviour. Since women are the central actors in reproduction, it is not surprising to find that the first wave of feminism in the 19th century was in part characterised by a desire to enable women to restrict their childbearing, albeit mainly to ensure that they could be better mothers to a few children, rather than poor mothers to too many.”

The morality of abortion

Traditionally, the debate as to the rights and wrongs of abortion has been couched in terms of the ‘right to life’ of the foetus versus the pregnant woman’s ‘right to choose’ whether or not to bear a child.

As Rosalind Hursthouse writes:

Hursthouse, R, Beginning Lives, Oxford: Blackwells, 1987, pp 27–28:

“The simplest view on the issue of abortion, the one often expressed explicitly or implicitly by non-philosophers in letters to newspapers, discussions on the wireless and so on, is that the moral rights and wrongs of abortion can be unproblematically settled by determining the moral status of the foetus. Hence it is common to find people on the conservative side insisting that the foetus is an unborn baby and hence that abortion is infanticide or murder and absolutely wrong, while people on the opposite side insist that the foetus is just a clump of living cells and hence that abortion is merely an operation which removes some part of one’s body and hence is morally innocuous…”

Fortin, J, ‘Legal protection for the unborn child’ (1988) 51 MLR 54:

- The concept of ‘personhood’

“… most philosophers argue that the point in time when human life begins is quite distinct from and less relevant than when a human ‘person’ comes into existence. The advantage of this approach is that it avoids the ‘speciesism’ involved in maintaining that all human life automatically has a greater intrinsic value and right to protection than that of any other species. Instead, it concentrates on those aspects of human life that merit such preferment. Thus whilst few would claim that a human sperm or unfertilised egg merits greater protection than a 10 week old kitten, most would accept without question the automatic right to life of a 10 year old child. This is because the child has become a person and as such, his life has an intrinsic value both to himself and others. Arguably then, there is little reason for extending legal protection to human life until ‘a person’ comes into existence. If this argument is accepted, it becomes vital to establish a clear definition of ‘personhood’; no easy matter when moral philosophers show little accord in their choice of essential attributes to be displayed by a ‘person’.”

Perhaps the most widely known to the general public is the traditional Roman Catholic approach to the question. This is a metaphysical one which, in its strictestform, maintains that a human person comes into existence at the moment of the ovum being fertilised. At this moment of ‘ensoulment’, the fertilised ovum becomes infused with a rational soul of its own and this theory of immediate animation is widely believed to embody the official teaching of the Roman Catholic Church …

Some Roman Catholic philosophers adopt the less extreme theory of ‘delayed animation’. This was developed by the theologian, Thomas Aquinas, who maintained that there were a number of stages in human generation and that ensoulment did not take place until a later stage, some time after conception. The more modern explanation is that a human soul can only infuse a human form which is sufficiently well developed to exhibit essentially human characteristics; clearly this does not occur until some time after conception.

Many moral philosophers reject the metaphysical approach to personhood which is so often associated with the Roman Catholic Church. In their view personhood is not defined by reference to the presence or otherwise of an immaterial human soul but by reference to a complicated combination of mental and or physical properties. There seems to be little agreement over which properties are essential, although many maintain that to be a person, a human being or entity must, inter alia, possess rationality and self consciousness, be capable of action and be the subject of non-momentary goals or interests. Inevitably, many proponents of such a combination of properties, find it impossible to accept that a human foetus can be deemed a person and worthy of protection; consequently, in their view, there can be no moral objection to abortion, however late. Indeed, Michael Tooley lucidly presents the argument that since even a newly born child lacks these properties, infanticide is not morally objectionable.

2. Human organisms, human beings and persons

Thus Michael Lockwood distinguishes between human organisms, human beings and persons. In this way, depending on the definition of ‘human being’, a newly born infant might be classified as such, with certain consequential rights, despite its not having attained the status of personhood. Lockwood uses the term ‘human being’ to describe what ‘you and I are essentially, what we can neither become nor cease to be, without ceasing to exist’. Thus, in his view, this concept revolves round that of personal identity, which underlies ‘certain discernible continuities’ such as memory and personality– those unchanging elements in a human being which establishes his own unique blueprint. Accordingly, the concept of identity is established not by the continuities themselves but by those elements underlying them …

In his view, it is only when the brain develops to this extent, that a human embryo can be said to have become a human being. Only then does it become able to sustain distinctively mental processes, thereby justifying certain protection. Lockwood himself feels that it is impossible to be precise over the point in time when this occurs. Nevertheless, on the basis of the existing, albeit sparse, scientific evidence, he suggests that an appropriate marker might be 10 weeks’ gestation. Lockwood’s analysis is attractively clear and less cold blooded than that of Tooley. Moreover, it has the advantage of allowing both the unborn and the newly born child to have a measure of protection as human beings, without claiming either to be a fully fledged person.

However, it is apparent that all three views described by Fortin require some commitment to unprovable ‘metaphysical’ premises. As Margaret Brazier has noted:

Brazier, M, ‘The challenge for Parliament’, in Dyson, A and Harris, J (eds), Experiments on Embryos, 1990, London: Routledge, p134:

Thus the argument on abortion becomes for opponents: ‘How can the law permit the wanton destruction of human life?’ And supporters of liberal abortion laws respond: ‘By what right do you seek to impose your personal unprovable claims about God and the soul on others?’ The dispute reaches stalemate … The humanity of the embryo is unproven and unprovable. But that acts both ways. Just as I cannot prove that humanity was divinely created and that each and every one of us possesses an immortal soul, so it cannot be proved that it is not so. Admitting the possibility of the soul, the moment of ensoulment cannot be proved. Nothing more or less can be concluded about the full humanity of the embryo save to say that the cases for and against are, to borrow a Scottish term, not proven.

In a telling recent contribution to the abortion debate, Ronald Dworkin has attempted to bridge the gap between the ‘pro-life’ and ‘pro-choice’ positions by identifying an important piece of common ground between the two camps. In particular, he argues that both conservatives and liberals share a commoncommitment to the sanctity of human life:

Dworkin, R, Life’s Dominion: An Argument About Abortion and Euthanasia, 1993, London: HarperCollins, pp 88–90:

“Both conservatives and liberals assume that in some circumstances abortion is more serious and more likely to be unjustifiable than in others. Notably, both agree that a late term abortion is graver than an early term one. We cannot explain this shared conviction simply on the ground that foetuses more closely resemble infants as pregnancy continues. People believe that abortion is not just emotionally more difficult but morally worse the later in pregnancy it occurs, and increasing resemblance alone has no moral significance. Nor can we explain the shared conviction by noticing that at some point in pregnancy a foetus becomes sentient. Most people think that abortion is morally worse early in the second trimester –well before sentience is possible – than early in the first one … Foetal development is a continuing creative process, a process that has barely begun at the instant of conception. Indeed, since genetic individuation is not yet complete at that point, we might say that the development of a unique human being has not started until approximately 14 days later, at implantation. But after implantation, as foetal growth continues, the natural investment that would be wasted in an abortion grows steadily larger and more significant.”

Abortion and legislation

Hursthouse, R, Beginning Lives, Oxford: Blackwells, 1987, pp 15–16:

“The confusion of questions about morality and legislation is particularly common in arguments about abortion … One reason why the questions become readily confused in debate is because of the tactics of opposition. Many people, particularly women, do think there is something wrong about having an abortion, that it is not a morally innocuous matter, but also think that the current abortion laws are if anything still too restrictive, and find it difficult to articulate their position on the morality of abortion without, apparently betraying the feminist campaign concerning legislation. To give an inch on ‘a woman’s right to choose’, to suggest even for a moment that having an abortion is not only ‘exercising that right’ (which sounds fine) but also ‘ending a human life’ (which sounds like homicide) or even ‘ending a potential human life’ (which sounds at least serious) is to play into the hands of the conservatives.”

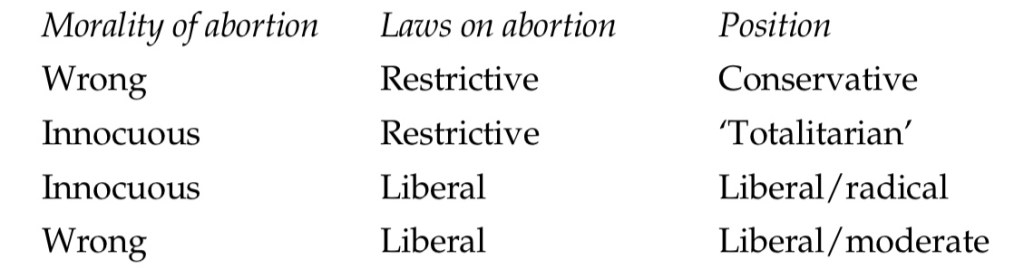

What happens to the conservative and the liberal sides of the debate once the distinction between questions of morality and questions of legislation is drawn? In theory, drawing the distinction opens up the possibility of four different positions.

The ‘totalitarian’ position is of merely theoretical interest. (It might be occupied by someone in an underpopulated country, indifferent both to women’s rights and to appeals to the sanctity of life, who thought it was necessary to increase the population quickly.) The first position is a familiar one. It is well known that the conservative position on legislation about abortion is based on a corresponding conservative position about its morality. According to the conservative view, abortion is morally wrong because it is the taking of human life, and hence, like any other case of homicide, justifiable in only a restricted range of circumstances, which should be laid down by law.

It is the possibility of two distinct liberal positions, which for want of better labels I will henceforth distinguish as the ‘radical’ and the ‘moderate’, which is not so familiar, and much that is said on the liberal side about women’s rights leaves it quite unclear which of two views about the morality of abortion its supporters hold. Do they hold that abortion is morally quite innocuous – and hence that to have laws restricting women’s access is as absurd and punitive as having laws which decreed, say, that women (though not men) were forbidden to cut their hair or smoke? Or do they agree with the conservatives that it is a morally very serious matter but hold that nevertheless the suffering and lack of freedom that women must at present undergo when abortion is not legally available not only justify but require our having laws which permit this wrong to be done whenever the woman wishes it? Is abortion a necessary evil as things are at present, or not an evil at all?

Wisconsin and Louisiana’s Scenario

Republicans ‘Ban’ Abortion in Blue States

Part of the Republicans’ Big Beautiful Bill includes a stipulation (that Planned Parenthood is challenging in court) that no federal funding or Medicaid dollars would be given in clinics that provide abortion. It was already against the law to any organisation to use federal dollars towards abortion services other than for cases of rape, incest, or to save the life of the pregnant person. In other words, no one’s tax dollars were being used to fund abortions. Activists say this was a targeted move to finally ‘defund’ Planned Parenthood, a long-term goal of Republicans. Medical facilities, including Planned Parenthood, “need” that money to stay open. So, the Wisconsin branches, even though they are in a state where abortion is legal, will stop performing abortions since they cannot afford to lose the federal money. In the year of 2022, thousands of Wisconsinites filled the states capitol to protest against abortion restriction. In fact, 200 of already running clinics are at risk of being closed throughout the country, this includes the states where abortion is legal.

“Planned Parenthood of Wisconsin will continue to provide the full spectrum of reproductive healthcare-including abortion- as soon as we are able to.”

Tanya Atkinson, CEO and President of the Planned Parenthood Wisconsin.

Republicans Make Care Deserts Worse

Care Deserts; a county that does not provide obstetric care and obstetric professionals as there are no hospitals or birth centres. This would mean that essential services are scarce and there is less maternal and neonatal services delivered/poor health outcomes associated with reproductive services.

Louisiana’s two Planned Parenthood clinics which never performed abortions had to close this week due to Trump’s Big Beautiful Bill. The 11,000 patients who went to clinic for STI testing, cancer screenings, prenatal care, and other general healthcare services are now without the affordable and accessible care that planned parenthood provides.

This closure worsens Louisiana’s critical healthcare gaps. The state already has one of the highest rates of maternal mortality in the country, and much of the state is in a care desert, where hospitals and facilities with gynaecological or maternal healthcare are scarce. The Hyde Amendment has existed since 1976 prevents the use of dollars for any abortion services other than in extreme cases such as incest or rape. The proposed bill would make the state’s strict six week abortion ban even stricter, by making the punishment for getting an abortion or helping others seek abortions the same as if it were ‘the homicide of a person born alive,’ with up to 30 years in prison, or, because South Carolina institutes the death Penalty, possibly sentenced to death.

“This bill, drafted by the National Right to Life, is a blueprint for what Republicans want across the country.”

Jessica Valenti, Abortion Everyday

England and Wales Scenario

British MPs have voted to decriminalise abortion in England and Wales after concerns sparked by the prosecution of women ending their pregnancy. The amendment passed 379-137 in parliament, meaning women who terminate their pregnancy after 24 weeks, will no longer be at risk of being investigated by police. The House of Commons will now need to pass the crime bill, which is expected, before it goes to House of Lords, where it can be delayed but not blocked.

Abortion

The European courts have looked at Article 2 of the Convention with regard to abortion on several occasions. In a case where a prospective father challenged the right of his ex-partner to obtain termination of pregnancy (Paton v UK (1980)), the courts rejected the notion that the foetus has an absolute right to life. In a later case (Vo v France (2005)), the court suggested that the foetus deserved to be treated with dignity, but did not go as far as to ascribe the foetus Article 2 rights.

Consequentialism does pose two very challenging problems for its proponents. One is the question of determining what does actually constitute a good outcome. If we are thinking about the ethics of abortion, for example, should we take into account the foetus’s interests, or only those of the mother? Another difficulty relates to the question of whether we should think only of the interests of existing people, or if we should also consider future generations— people who do not yet exist.

See: Previously on the Must-Knows of Consequentialism and Deontology as a Practising Doctor

Kant’s philosophy does not help very much in determining the moral status of abortion, for example. Fetuses are not rational per se, so it might seem that they lack moral status on a deontological view, in which case abortion might be permissible. However, in practice, many deontologists are opposed to abortion.

📰 News Updates Global:

Sources:

- Sourcebook on Medical Law

- Philosophical Foundations of Medical Law

- Oxford Handbook on Medical Ethics and Law

- A Medic’s Guide to Essential Legal Matters

News:

- NowThis Impact

- 10 News

- Image Credit-Unsplash

(ps I’ve managed to compress the information as much as I can! Enjoy!♡)