If there was a chalkboard lied with the most repeated mantra of nutritional health, it would probably say “Saturated fats are bad” over and over and over again. This message was started in the late 1970s, and within a few years much of the Western world had rejected whole-fat milk, butter, and eggs. With the righteousness of heart health in hand, these foods were readily replaced with watery blue nonfat milk, vegetable-based margarine, and egg whites.

[W]e can look increasingly to nature for new approaches to cure diseases. By doing so, there comes the benefit of calling upon human health experts to improve animal and environmental health, too. This is the core of the global One Health movement. By taking exceptional care of one together, we can help many. Earth’s 8.7 million species, including the bottlenose dolphin, means 8.7 million chances to make big, positive changes, including better preventing, managing, treating, and curing diabetes. As we move forward, may we actively engage in applying One Health to work together—as physicians, veterinarians, scientists, and biologists—to improve health for all.

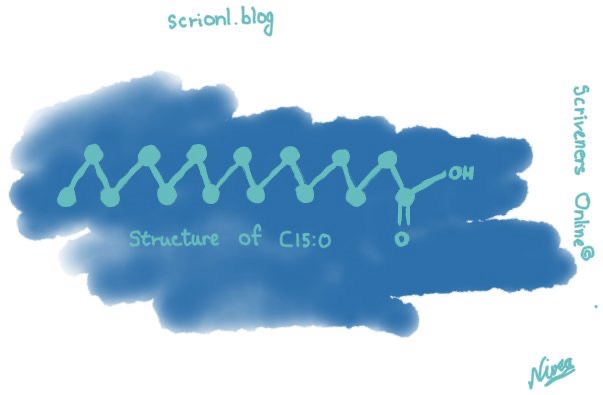

Saturated fatty acids are divided into two main categories: even-chain and odd-chain. Even-chain fatty acids have an even number of carbon atoms (like C16:0 and C18:0). Odd-chain fatty acids have an odd number of carbon atoms (like C15:0 and C17:0). Over and over again, large population studies have consistently shown that people with higher C15:0 and C17:0 levels have a lower risk of having type 2 diabetes and heart disease. Meanwhile, these same studies show that people who have higher C16:0 or C18:0 have a higher risk of having type 2 diabetes and heart disease. These differences go well beyond association, with directly demonstrated health benefits caused by C15:0 and, somewhat less so by C17:0. And they demonstrate disease-driving impairments caused by C16:0 and C18:0.

While there’s a lot more about these differences overed throughout this book, the main point here is that, despite a preponderance of science showing that (1) C15:0 and C17:0 odd-chain saturated fatty acids can contribute to good health, and (2) C16:0 and C18:0 even-chain saturated fats can contribute to poor health, the global nutritional community continues to put all saturated fat types into one big blob. For example, as we shared earlier, the USDA Dietary Guidelines for Americans (2020–2025) literally mentions limiting dietary saturated fats 161 times in their 164-page document. Similarly, the American Heart Association recommends no more than 5 to 6 percent of daily calories come from saturated fats. Neither the USDA nor the American Heart Association references differences between odd- and even-chain saturated fatty acids.

An Unexpected Discovery from Navy Dolphins

To understand how this all happened, we need to go back to 2001. As a veterinary epidemiologist, I was working for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the World Health Organization in Atlanta, Georgia. So, what exactly is a veterinary epidemiologist? Simply put, we are veterinarians who specialize in tracking diseases in animals, which can even include us bipedal mammals. While movies would have you believe that, as adventurous animal- disease trackers, we urgently hack our way through dense jungles to find the source of a new virus that is rapidly spreading through Los Angeles half a world away, the reality is that a lot of our time is spent at a desk. As this was my first official job after graduating from veterinary school, my primary residence was a cubicle in the sub-sub-basement. Discman spinning and headphones on, I spent hours and hours writing code and churning through data to look for patterns. Like patterns around salmonellosis caused by reptiles.

One of my first tasks was to better understand the risk of infectious diseases to Navy dolphins. At the time, wild dolphin populations, especially those along the East Coast and in the Gulf of Mexico, were succumbing to a form of measles, called dolphin morbillivirus.3 This highly infectious virus was causing mass mortality events along multiple US shorelines that killed wild dolphins so quickly that, other than being dead, they looked perfectly healthy. Understandably, the Navy wanted an assessment of infectious diseases that were the highest risk to Navy dolphins—and just as important, how to protect the dolphins from getting sick.

Over the next ten years, we dove into the electronic medical records, analyzed archived serum and tissues, and read piles of histology reports to better understand lower-lying chronic conditions that developed as dolphins got older. This took a while because, unlike people who routinely exchange stories about each other’s aches and sleepless nights, dolphins have evolved to purposely hide their illnesses as part of a survival mechanism. If you’re a dolphin, it isn’t a good idea to reveal to potential predators that your shoulder joint is feeling a bit stiff this morning. So, we relied on all that health data the Navy had meticulously collected.

Here’s what we found. In general, as dolphins get older, their cholesterol and triglyceride levels go up, as well as generalized inflammation.5 Some of these older dolphins go on to develop a chronic condition called metabolic syndrome, which is a cluster of multiple conditions including insulin resistance and elevated glucose, cholesterol, and triglycerides.6 In humans, metabolic syndrome affects at least one in four people globally, and also includes symptoms like excessive belly fat and hypertension.7 Lacking our couch-slouching television watching time and salty potato chip snacks, Navy dolphins stay physically fit, and obesity is not a contributor to their metabolic syndrome. And we discovered that it was hard to tell if hypertension is an issue; dolphins shunt blood vessels away from the skin surface to conserve body heat in cold waters, which makes blood pressure cuffs difficult to use on our finned friends. All that aside, we were seeing many of the components of metabolic syndrome in older dolphins.

In addition to metabolic syndrome, we discovered a couple of other familiar chronic conditions in dolphins. First, upon taking a closer look through the microscope at archived liver tissues, we found that some dolphins had developed a condition called fatty liver disease.8 As you smartly guessed or already knew, this is a disease involving excessive fat deposition in the liver. (We’ll talk more about the alarming global rise of metabolic dysfunction–associated steatotic liver disease, aka fatty liver disease, among humans in Chapter 6.) Second, by analyzing archived dolphin brains, which had been oating in well-cared-for containers on shelves affectionately called the “dolphin brainery,” we discovered that some older dolphins developed tissue-based changes nearly identical to those seen in early stages of Alzheimer’s disease in humans. These parallels between dolphin and human Alzheimer’s disease have also been reported in wild dolphins.9 The more we looked through the Navy’s treasure trove of dolphin health records and samples, the more we understood how dolphin health changes with age, and the more that older dolphins looked like older humans.

Understanding How Chronic Diseases Emerge as We Age

Over the next decade, many of our initial skeptics would become our mostpowerful advocates. When we first discovered links related to prediabetes in dolphins and humans, however, we still encountered pushback. In 2007, we wrote our 1st scientific manuscript specifically detailing these parallels, titled “Big Brains and Blood Glucose: Common Ground for Diabetes Mellitus in Humans and Healthy Dolphins.” After uploading this paper to the journal Diabetes, I hit the Submit Manuscript button and headed to our weekly veterinary team meeting. Upon returning to my desk ninety minutes later, I found an email from an editor awaiting my click, stating that our paper was not suitable for their journal since dolphins are not relevant to human health. There’s a decent chance that was the quickest rejection of a scientific paper— ever. We ended up publishing this study in Comparative Medicine.10

The good news was that our studies with the Navy were always squarely focused on continually improving Navy dolphin health, and the potential to benefit public health had always been a bonus. So, as the human health world was working through its fair skepticism, we continued to discover and understand aging-related conditions in dolphins. Thanks to support from the Office of Naval Research, we spent the next decade figuring out why some older dolphins—but not all—were developing insulin resistance, metabolic syndrome, and fatty liver disease. Most important, we were discovering new ways to prevent, treat, and possibly even cure these diseases.

On the Precipice of a Big Discovery

To test the hypothesis that higher levels of omega-3 fatty acids protected dolphins against developing chronic conditions, we relied on two dolphin populations. First, we compared Navy dolphins living in San Diego Bay with wild dolphins living in Sarasota Bay, Florida. Although the lifespans of wild dolphins are, in general, shorter than those of Navy dolphins, the health of Sarasota Bay dolphins has been incredibly well documented for decades. This effort is thanks to a team of dedicated marine biologists at the Sarasota Dolphin Research Program, a group who has also contributed substantially to dolphin health science and conservation efforts. Relative to most other wild dolphin populations, Sarasota Bay dolphins are downright healthy. For our second population comparison group, we looked at dolphins within the Navy population that had or didn’t have metabolic syndrome. By comparing these dolphin populations, we found three important hints.

Hint #1: Sarasota Bay dolphins are less likely to have signs of metabolic syndrome compared to Navy dolphins. In our initial study comparing Navy and Sarasota Bay dolphins, we found that Navy dolphins had higher insulin, cholesterol, and triglycerides.12 While Navy dolphins were indeed older, this low-lying trend was also present among some young adult dolphins, suggesting that there might be something about Sarasota Bay dolphins that further reduced the risk of subclinical metabolic syndrome during dolphins’ younger years.

Hint #2: Dolphins with higher levels of an odd-chain saturated fatty acid had lower, healthier insulin levels. We compared fatty acid levels between Navy and Sarasota Bay dolphins. Alas, there were no dierences in omega-3s. We did, however, find something interesting. Dolphins with higher blood levels of an odd-chain saturated fatty acid called C17:0 (pronounced see-seventeen) had lower, healthier insulin levels. 13 A quick search of the scientic literature revealed that odd-chain saturated fatty acids, such as C17:0 and C15:0, can be present in some types of fish.

Hint #3: When Navy dolphins were fed fish containing more odd-chain saturated fatty acids, their metabolic health normalized. Our next step was pretty reasonable. We measured C17:0 and C15:0 in different types of fish eaten by Navy dolphins. This included capelin, herring, mackerel, and squid. We did the same for fish eaten by Sarasota Bay dolphins—specifically, mullet and pinfish. We found that capelin and squid—staples of the Navy dolphin diet—had no detectable odd-chain saturated fatty acids, including C17:0 and C15:0. In contrast, Sarasota Bay mullet and pinfish did have these odd-chain saturated fats. So did herring and mackerel.

So, we provided six Navy dolphins with a Sarasota Bay diet consisting of mullet and pinfish for six months. By doing so, we successfully increased their dietary odd-chain saturated fatty acid intake (especially C17:0 and C15:0) more than fourfold compared to their baseline diet, while not significantly changing their omega-3 intake. Within one month, the Navy dolphins’ C17:0 and C15:0 blood levels increased. More important, their insulin and triglyceride levels normalized. Now we were talking. We published this initial study in the peer-reviewed Public Library of Science (aka PLoS ONE) in 2015.15

The Cell Membrane Pacemaker Theory of Aging

In 2005, A. J. Hulbert shared a fascinating theory, referred to as the Cell Membrane Pacemaker Theory of Aging. 13 In his studies, Hulbert showed that longer-lived mammals had sturdier fatty acids in their cell membranes. By simply stabilizing the outer building bricks of our cells, long-lived mammals effectively increased their whole-body resilience against death. Voilà! Extended longevity.

Hulbert’s Cell Membrane Pacemaker Theory of Aging

Hulbert showed that mammals with more fragile fatty acids in their cell membranes had more fragile cells, resulting in shorter lifespans.

Rapamycin, the Longevity Leader

Originally discovered in bacteria growing on Easter Island, rapamycin was initially found to have antifungal properties.16 That’s why it is named rapamcyin: rapa (for the native name of Easter Island, Rapa Nui) and mycin (a term commonly used for antimicrobials). Over the past fifty years, rapamycin has been found to do a lot of good things. 17 To start, rapamycin has anticancerproperties. Additionally, owing to its ability to break apart abnormally concentrated bulbs of scarlike tissue (aka fibromas), this drug is approved by the FDA to treat certain types of fibrotic diseases. Further, rapamycin modulates the immune system, which helps our bodies accept organ transplants without attacking those organs as foreign invaders. All in, rapamycin provides a mixed bag of tricks that, albeit odd, are quite effective in extending longevity, at least in mice. When we look at our first five criteria for longevity molecules, rapamycin is a strong contender. First, rapamycin targets that hallmark of aging called cellular senescence.18

Rapamycin prevents cellular senescence by inhibiting a key mechanism, called mTOR. In turn, slowing mTOR can extend longevity.19

Rapamycin, however, does more than just target a key hallmark of aging and the longevity pathway. As we hinted, this drug has clinically relevant activities across multiple organs that doctors care about, including being: 20

• Anti-inflammatory

• Antifibrotic (aka prevents tissue scarring)

• Anticancer; and

• Antimicrobial

Further, when tested in mice, rapamycin repeatedly extends the lifespan of both females and males.21 For all these reasons, rapamycin has had the top spot on the longevity leaderboard for the last half decade or more. What is missing from rapamycin’s repertoire, however, are large-scale human studies.

Metformin, an Oldie but Goodie

Unlike rapamycin, there is a candidate drug for enhancing longevity that is already commonly and safely used by millions of people globally. Which brings us to our second potential longevity molecule: metformin. As a frontline drug to manage type 2 diabetes, metformin is one of the most commonly used drugs throughout the world. 24 Metformin is an old, old drug. Like centuries old. Initially discovered in the French lilac, metformin has long been used to keep our blood sugars down. 25

Uncovering C15:0 as the Longevity Nutrient

Effects of C15:0 on Hallmarks of Aging and Longevity Pathways

Hallmark 1. C15:0 has the power to stop senescent zombie cells. In 2022, a research team in Jeju, South Korea, was evaluating C15:0 for anticancer activities when they discovered it blocked mTOR.

6

Hallmark 2. C15:0 calms the inflammation of aging. As we get older, our bodies (and minds) increasingly suer from a slow-brewing but constant state of inflammation. In turn, chronic inflammation speeds up our aging-related breakdown. At the end of 2017, we evaluated a slew of C15:0’s cell-based activities by using an industry-standard panel called BioMAP. We’ll go into more detail about this panel at the end of this chapter, but for now it is important to note that among C15:0’s many benefits, we discovered this good fat directly targets inflammaging by lowering eighteen pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines, including IL-6 and MCP-1. So, that’s two hallmarks of aging down.

Hallmark 3. C15:0 repairs mitochondrial function.

When cells are healthy, mitochondria make ATP. That’s good for our cells, and good for us. When mitochondria think our cells are compromised, however, they stop making ATP and start activating a kill switch for the entire cell. Specifically, our mitochondria turn into factories of toxic reactive oxidative species, called ROS. When we get older, our mitochondria become inappropriately trigger-happy and prematurely switch from making ATP to making ROS, which makes us age even faster.9

Hallmark 4. C15:0 restores our cellular signaling.

When we talk about cellular communication, the main players are messengers (molecules) and receivers (cellular receptors). The better a molecule into the receptor, the stronger the signal. So, the trick here is the t. If it’s too loose, the message won’t get picked up. If it’s too tight, the molecule gets stuck and locks up the receptor for longer than it should. The best t is like a handshake. It’s a good, rm connection between a molecule and a receptor to pass on a message of

“Turn it up” or “Turn it down,” followed by an easy departure.

To date, C15:0 is known to have the following seven receptor-based activities:

1. mTOR inhibitor

2. PPARα activator

3. PPARδ activator

4. AMPK activator

5. AKT activator

6. HDAC-6 inhibitor

7. JAK-STAT inhibitor

Hallmark 5. C15:0 slows epigenetic alterations.

Hallmark 6. C15:0 improves gut microbiota health.

When our gut microbiome is imbalanced, this is called gut dysbiosis. This is why, in 2023, gut dysbiosis was added to the coveted list of hallmarks of aging.27

In a randomized and controlled clinical trial led in Singapore and published in 2024, women who took a daily C15:0 supplement for twelve weeks had signicantly higher levels of a healthy gut microbe called Bifidobacterium adolescentis.28 What does this good bacterium do, you ask? Well, it’s quite the gut superhero, with the demonstrated ability to improve both healthspan and lifespan across multiple species.29

Bifidobacterium adolescentis naturally decreases in abundance in our gut as we get older (specifically, as we surpass 60 years of age).30 Premature aging mice dosed with this good bacterium demonstrated improvements in both osteoporosis and neurodegeneration. Bifidobacterium adolescentis treatment in both flies and worms resulted in longer healthspan and lifespan. Bifidobacterium adolescentis’s longevity-supporting skillset appears to be due to its ability to increase catalase production. Ah, but what is catalase? This enzyme is a powerful antioxidant that decreases as we age.31 Restoring catalase levels has shown promise in addressing multiple aging-associated diseases, including type 2 diabetes, Alzheimer’s disease, and Parkinson’s disease. As such, the demonstrated ability for C15:0 supplementation to effectively increase the good gut microbe, Bifidobacterium adolescentis, addresses our sixth hallmark of aging, dysbiosis. And the fact that this microbe is a longevity-enhancing microbe?Score.

Evidence that C15:0 Slows Aging in Clinically Relevant Ways

Dr. Nicholas Schork is a population geneticist and leading expert in longevity. So much so that Nik leads the National Institutes of Health’s Longevity Consortium, which is an impressive group of scientists throughout the country who study all aspects of aging, with the intent of helping us live longer and healthier lives. When Nik learned about the Navy dolphins and their health data, including forty-four clinical blood values that are routinely collected throughout dolphins’ thirty- to fifty-year lifespans, he said,

“Stephanie, I bet you can show what everyone knows but few have been able to prove convincingly.”

“Well, that sounds exciting. What would that be?” I asked, while we were grabbing a coffee together in one of San Diego’s many techy cafés.

“That individuals within the same population age at different rates over their lifetimes,” he answered.

Let’s dig in here. It is well established that certain factors can increase our risk of getting aging-related diseases earlier. Factors like smoking, or drinking, or one’s economic status and lack of access to good healthcare. But what happens when you take a population of humans who have grown up in the same environment, eaten the same diet, and received the same healthcare for their entire lives? Will different people within this population still age at different rates?

So, back to the dolphins. No kidding; it took less than three weeks from that initial cup of coffee with Nik to his winning his bet. Given that we already had lifetime routine health data from more than a hundred Navy dolphins, we were able to work with the Navy to quickly discover blood-test indices that significantly tracked with advancing age.

32 These four aging rate markers were:

• Declining haemoglobin

• Declining lymphocytes

• Declining alkaline phosphatase

• Declining platelets

Studies on C15:0 and Longevity in Humans

One large study, published in 2019, tracked the health and diets of 14,383 adults over an average of fourteen years. The researchers especially looked into this population’s dietary saturated fatty acid intake over time. They also tracked mortality to determine which saturated fatty acids, eaten over time, led to either an increased or a decreased risk of death. This large prospective clinical study conducted over a long period of time had two key findings. First, people who had more of the saturated fatty acids C16:0 and C18:0 in their diets were more likely to die during the study period—especially, women. Second, those who had the highest amount of the saturated fatty acids C15:0 and C17:0 in their diets had lower mortality rates; this benefit of C15:0 held true for both men and women. So, chalk one up for C15:0 and longevity.

The second study compared people living in a mountainous area of Sardinia, Italy, with people living in a different part of northern Sardinia. 59 Both sets of people were in their sixties. Why these two regions, you ask? Well, the mountainous area of Sardinia is considered a High Longevity Zone, where people have fewer chronic diseases and consistently live to one hundred years old. In contrast, northern Sardinia is considered a Low Longevity Zone. In this study, the researchers found that people living in the High Longevity Zone had higher C15:0 blood levels compared to those in the Low Longevity Zone. While associative, this result supports this chapter’s point that C15:0 causes longer life.

There was new hope when the World Health Organization (WHO) acknowledged that there has been an ongoing debate regarding dietary saturated fats, and their updated 2023 guidelines incorporated input from experts following their review of saturated fat science.5 The result? The WHO doubled down on their original recommendations, concluding that dietary saturated fats should be limited to no more than 10 percent of our daily caloric diet. The strongest evidence for lowering intakes of dietary saturated fat, as stated by all three of these nutritional and health authorities, is that dietary saturated fats increase bad LDL cholesterol, which increases the risk of heart disease.6 Yet multiple studies, including a controlled clinical trial, have shown C15:0 lowers total and LDL cholesterol. Further, people with higher C15:0 levels are more likely to have lower cholesterol and a lower risk of heart disease.

8

Before we villainize the world’s leading nutritional guidelines, however, here’s the rub. As will be shared in Chapter 12, all foods that contain C15:0 and C17:0, including dairy fat, red meat, and plant fats, also contain even-chain saturated fatty acids, especially C16:0 and C18:0. Further, these foods always have much higher amounts of even-chain saturated fatty acids compared to odd-chain saturated fatty acids. We’re talking typically greater than 40 percent of fatty acids being C16:0 and C18:0, and less than 5 percent being C15:0 and C17:0. In general, the highest C15:0-containing foods have only about 1 percent of C15:0 among total fatty acids.

…our bodies do not make enough C15:0 to support a reduced risk of type 2 diabetes and that we must get adequate amounts of C15:0 routinely from our diet. Additionally, the WHO argues that odd-chain saturated fatty acids are present at such low levels in foods, compared to harmful even-chain saturated fatty acids, that any potential health benefits of C15:0 and C17:0 are grossly outweighed by the detrimental effects of C16:0 and C18:0.

Fatty acids that have only single bonds (like C15:0 and C16:0) are saturated fatty acids. In contrast, fatty acids that have double bonds in their main chain are called unsaturated fatty acids. If a fatty acid has multiple double bonds (like with EPA), it is called a polyunsaturated fatty acid. Importantly, these double bonds act like hinges, which serve as bending points for unsaturated fatty acids.

Saturated Fatty Acids: Odd- versus Even-Chain

Odd-chain saturated fatty acids (like C15:0 and C17:0) are associated with good health, while even-chain saturated fatty acids (like C16:0 and C18:0) are associated with poor health.

Source: The Longevity Nutrient- Dr Stephanie Venn-Watson (2025)