CHS cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome has risen in the US emergency departments between 2016 and 2022 and have continued to remain up as discovered by researchers at the Jane Addams College of Social Work at the University Illinois Chicago. Statistics show that as of June 2025 close to half of the US residents residing in the cannabis legal states, have an expanded access to the adult use, the medical programs and the decriminalisation. CHS is described as a growing concern in the public health and clinical settings.

CHS was first identified in Australia in 2004 and continues to remain as a syndrome of unknown aetiology.

Study authors argue that emergency clinicians and public health systems need preparation for the consequences of increased cannabis use, particularly in regions where legalisation is recent and exposure to high-potency cannabis products is expanding. CHS may be under-recognised in those settings, with failure to identify the syndrome contributing to unnecessary diagnostic testing and ineffective treatment courses. 24 states, two territories and the District of Columbia have legalized small amounts of cannabis (marijuana) for adult recreational use.

In the study, “Cannabinoid Hyperemesis Syndrome, 2016 to 2022,” published in JAMA Network Open, researchers conducted a cross-sectional analysis to estimate CHS prevalence in US emergency departments, assess temporal trends from 2016 to 2022, and examine socio-demographic associations.

Clinical guidelines to increase awareness and decision-support tools are possible strategies to help clinicians distinguish CHS from other gastrointestinal conditions, especially among younger adults with chronic cannabis exposure. Targeted screening for cannabis use and careful attention to symptom patterns, including recurrent severe nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, and compulsive hot bathing, are suggested as ways to improve diagnostic accuracy.

Clinical Presentation

The Rome IV criteria categorize functional nausea and vomiting disorders into three types: chronic nausea and vomiting syndrome, cyclic vomiting syndrome (CVS), and CHS. The main symptoms of CHS include repetitive vomiting episodes occurring in individuals with chronic, daily cannabis use, with relief of symptoms following the cessation of cannabis use. It is crucial to differentiate CHS from CVS for appropriate management. Many times, CHS presents as epigastric abdominal pain, often accompanying nausea and vomiting, though Rome IV does not include it. The vomiting and abdominal pain are suppressed by hot showers, possibly due to their relaxation and distraction effects. There are periods of well-being or remission lasting from days to weeks between the symptoms episodes. However, attacks may become more frequent over time if there is continued usage of cannabinoids.

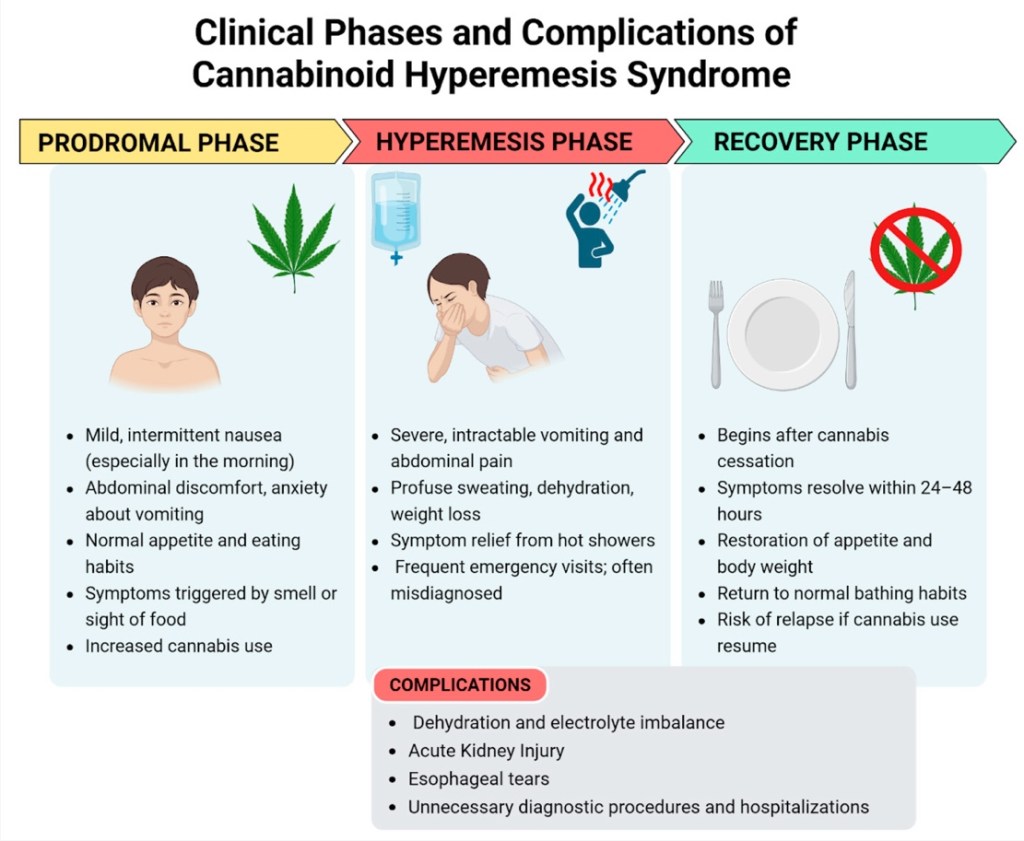

CHS involves 3 phases: prodromal, hyperemesis, and recovery.

Prodromal Phase

The prodromal phase can be present for several months. During this phase, patients may experience morning nausea, abdominal discomfort, or anxiety about vomiting. Despite these GI symptoms, patients often eat well, maintain weight, and remain functional at work. The patients continue using cannabis in this phase, believing in its anti-nausea effects.

Hyperemesis Phase

The hyperemesis phase can last for several days. This phase begins with severe symptoms that intensify rapidly within a few hours [54]. Patients present with distressed stomach, intense, persistent nausea, and frequent vomiting, feeling as though a relapse is imminent in this phase. This episode is debilitating and overwhelming, with patients vomiting and retching up to five times per hour, requiring several emergency room (ER) visits. Abdominal pain generally starts in the epigastric region and progresses to more diffuse abdominal pain. The intense diffuse abdominal pain may sometimes need extensive diagnostic workup, including biliary scans to rule out acute cholelithiasis or choledocholithiasis and multiple computed tomography (CT) imaging to rule out acute abdominal conditions, including pancreatitis. A sympathetic overactivity during this phase results in symptoms such as tachycardia, hypertension, hot flashes, sweating, and trembling [42]. Due to excessive nausea and vomiting, patients are often found to have hypokalemia, volume depletion, acute renal failure, hypophosphatemia, and mild reactive leukocytosis [55,56,57]. Multiple and forceful vomiting events can cause Mallory–Weiss tears with hematemesis and rarely lead to pneumomediastinum or Boerhaave’s syndrome [58].

Recovery Phase

In this phase, patients gradually resume normal eating and dietary habits. Patients experience complete relief of the symptoms, which can last days, weeks, or even months. The duration of this phase ranges from weeks to months, depending on resuming marijuana use, which may trigger another relapse. Throughout this phase, the patient maintains an average weight and returns to their baseline state [49].

Pathological Bathing Behaviour

Several previous studies have described the characteristics of frequent and prolonged hot shower use common among patients with CHS. Patients often adopt this behaviour to alleviate nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain symptoms of CHS, and some reports have referred to this symptom as CHS as “cannabis hot shower syndrome”. It is hypothesised that hot showers help stabilise the thalamic thermostat, which is frequently disrupted by chronic cannabis use, including CHS. Often, they are used as a self-treatment in CHS. However, this proposed mechanism has not been empirically validated [59]. Though many patients with CHS may use hot bathing or showering to obtain relief from its symptoms, more than 10% may not exhibit this behaviour [60].

Additionally, similar patterns of hot shower behaviours are observed in cyclic vomiting syndrome (CVS), as well as in preadolescents and adolescents with no history of cannabis use [61]. Thus, hot showers may be associated with CHS; they are not a unique diagnostic feature of CHS and are not included in the Rome IV diagnostic criteria [62]. CHS has more male predominance and, similar to CVS, primarily affects young people.

Pituitary–Adrenal Axis

Cannabinoids affect the pituitary–adrenal axis and stress-responsive brain regions. Studies suggest that CHS may involve disruption at the hippocampal–hypothalamic–pituitary level [22]. Chronic cannabis use can lower pituitary hormone levels, including the growth hormone, follicle-stimulating hormone, and luteinising hormone, which has been shown to normalise after stopping use [23,24].

Diagnosis

The first diagnostic criteria for CHS were identified in 2009 by Sontineni et al. [4]. Then, in 2012, a case series involving 98 patients was published by the Mayo Clinic, revising and expanding the diagnostic criteria to include severe cyclic nausea and vomiting, abdominal pain, weekly marijuana use, symptom relief with hot showers or baths, and resolution with cannabis cessation as major criteria [5]. In 2016, the Rome IV criteria, currently the most widely used for diagnosing CHS, were established. However, these criteria were developed using data from the adult population. These diagnostic criteria required the resolution of vomiting episodes after prolonged abstinence from cannabis, although the exact timeframe for symptom resolution was not clearly defined. The characteristic behavior of “hot water bathing” was considered a supporting criterion, despite that, actually, it also occurs in approximately 50% of patients with CVS who do not use cannabis [3].

Failure to recognise this disorder can result in multiple ER visits and extensive recurring serum testing and imaging evaluations with increased healthcare-related costs. It is crucial to exclude other entities such as Addison’s disease, migraines, hyperemesis gravidarum, bulimia, and psychogenic vomiting, which can mimic CHS symptoms and may also occur alongside it. A thorough medical history, complete physical examination, and focused diagnostic testing help differentiate from these other differential conditions. CHS is classified as a type of functional gut–brain disorder and a variant of cyclic vomiting syndrome (CVS) per the Rome IV structured framework. However, it is essential to differentiate CHS from CVS.

Management

The management of CHS largely relies on the severity of symptoms, the emergence of complications, and measures to prevent future recurrence. Evidence-based management of CHS is based on case series and small clinical trials [63]. The recent 2024 American Gastroenterology Association (AGA) clinical practice update recommended combining evidence-based psychosocial interventions and pharmacological treatments for the successful long-term management of CHS [63].

Cessation of Cannabis:

Discontinuation of cannabis use in any form is required for complete long-term management of CHS. A multimodal approach, including structured psychotherapy such as cognitive behaviour therapy (CBT), along with addiction counselling in educating patients about the consequences of cannabis use, is necessary [92]. Some patients may require rehabilitation programs to monitor the patient’s progress, ensure treatment adherence, and offer therapeutic support to achieve and maintain recovery. Mutual help groups such as Marijuana Anonymous are beneficial to patients without access to structured programs.

Source:

https://medicalxpress.com/news/2025-12-chronic-cannabis-vomiting-compulsive-symptoms.html

https://www.mdpi.com/1424-8247/17/11/1549

https://www.mdpi.com/2036-7503/17/4/75

https://www.ncsl.org/civil-and-criminal-justice/cannabis-overview

Picture Credit: Unsplash