The Nipah virus was first identified in April 1999 on a pig farm in peninsular Malaysia when it caused an outbreak of neurological and respiratory disease. The outbreak resulted in 257 human cases, 105 human deaths, and the culling of 1 million pigs.

Geographical Distribution & Emergence

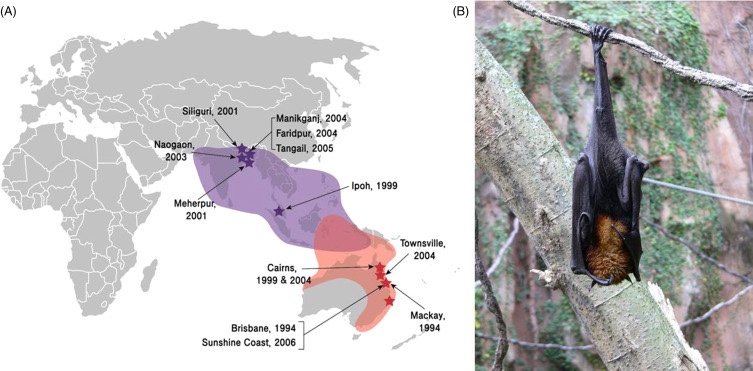

The emergence of NiV as a significant public health threat can be traced back to its first documented outbreak in Peninsular Malaysia between September 1998 and May 1999. This first outbreak, which resulted in 265 cases of acute encephalitis and 105 deaths, marked the introduction of the virus to the scientific community and highlighted its devastating potential. The outbreak mainly affected pig farmers and people in close contact with infected pigs, leading to the slaughter of over one million pigs to contain the spread. Concomitant cases in Singapore among slaughterhouse workers handling pigs imported from Malaysia further demonstrated the virus’s ability to spread geographically through the cattle trade.

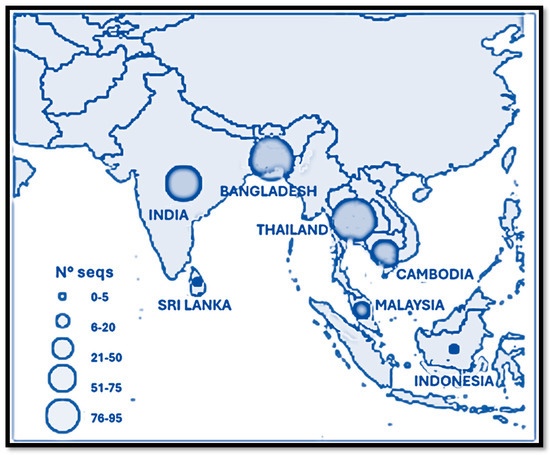

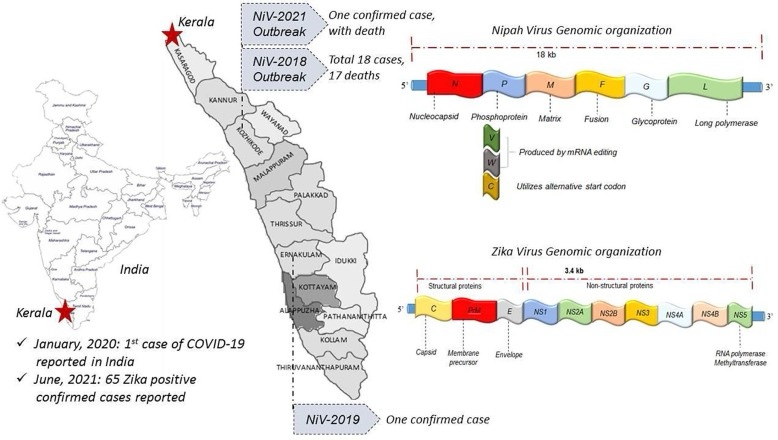

The pattern of NiV outbreaks has changed significantly since its initial identification, with Bangladesh and India becoming major hotspots for recurrent outbreaks. Since 2001, Bangladesh has experienced almost annual outbreaks, with a distinct epidemiological pattern characterized by sporadic cases and small clusters, mainly linked to the consumption of raw date palm sap contaminated by infected bats. These outbreaks follow a clear seasonal pattern, typically occurring between December and April, coinciding with the date palm sap collection period. During these months, Pteropus bats, the primary source of zoonotic transmission, are more active near human settlements, thereby increasing the risk of contamination and infection. The Indian state is another significant area for NiV transmission, the first documented outbreak of which occurred in Siliguri, West Bengal, in 2001, with 66 cases and a 74% mortality rate. This outbreak was particularly noteworthy for demonstrating efficient human-to-human transmission in a hospital setting. The state of Kerala, India, has emerged as a major hotspot for NiV outbreaks, with multiple incidents reported since 2018. The initial outbreak in May 2018 was particularly severe, resulting in 17 deaths out of 18 confirmed cases, with a staggering 94.4% mortality rate. Subsequent outbreaks in 2019, 2021, and 2023 reinforced the endemic potential of NiV in the region [13]. The latest outbreak, in September 2023, occurred in Kozhikode district following the death of a 14-year-old boy, again underscoring the persistent threat posed by the virus and the challenges to control its spread. (Up until now!)

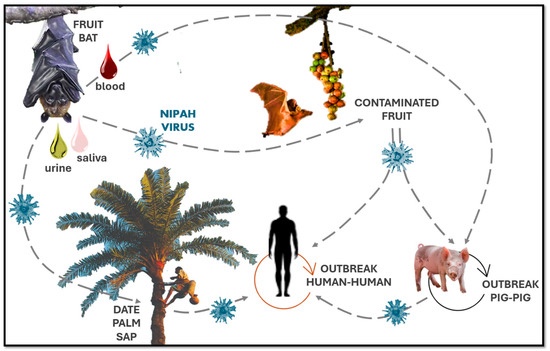

For example, zoonotic transmission in Bangladesh is often due to the consumption of raw date palm sap contaminated by bats. This local food practice, in which date palm sap is tapped from trees into open containers, presents a high risk of contamination, as bats are known to feed on this sap and may leave saliva or other fluids on the collection vessels. In Malaysia, pig farming was the main amplifying host of human cases, resulting in the rapid spread of the virus among pig farmers. Since then, the spread of the virus has been linked to different animals and human activities depending on local conditions, and the experience in Malaysia has prompted changes in livestock management practices to prevent similar incidents. Human-to-human transmission has emerged as a critical route of Nipah virus spread in Bangladesh and India, particularly within healthcare settings, where hospital clusters have been documented. The 2001 outbreak in Siliguri, India, highlighted this risk, with the virus spreading extensively among patients, healthcare workers, and family members. Similar clusters were observed during the 2018 and 2023 Kerala outbreaks, where direct contact with infected body fluids facilitated transmission.

Environmental and anthropogenically driven changes have also played a crucial role in shaping NiV epidemiology. Deforestation, agricultural expansion, and urbanization reduce natural habitats for Pteropus bats, bringing them into closer proximity to human populations. These bats adapt to human-altered environments, where they may seek food in agricultural lands or near residential areas, thus increasing the likelihood of zoonotic spillovers. For example, in Bangladesh, deforestation has decreased available habitats for bats, leading to higher interactions with people in rural settings, especially where date palm sap collection is common. Climate change may also influence NiV trans-migratory patterns and seasonal behaviors. For example, changes in temperature and precipitation can affect fruit and flowering seasons, altering bat feeding habits and potentially changing the timing and location of human–bat interactions. While the exact effects of climate change on NiV transmission remain under study, it is likely that climate-related shifts in bat behavior could impact the virus’s spread across different regions and seasons.

Molecular studies have provided insights into NiV’s evolution and pathogenic potential. Two primary genetic strains of NiV have been identified: the Malaysian strain, which was responsible for the initial outbreak, and the Bangladeshi strain, associated with more recent cases in Bangladesh and India. The Bangladeshi strain has demonstrated greater genetic variability and higher virulence, with mortality rates exceeding 75% in some outbreaks. This strain’s ability to spread through human-to-human transmission in healthcare settings underscores its elevated public health risk compared to the Malaysian strain, which has shown limited human-to-human transmission.

Its Spread & Virulence

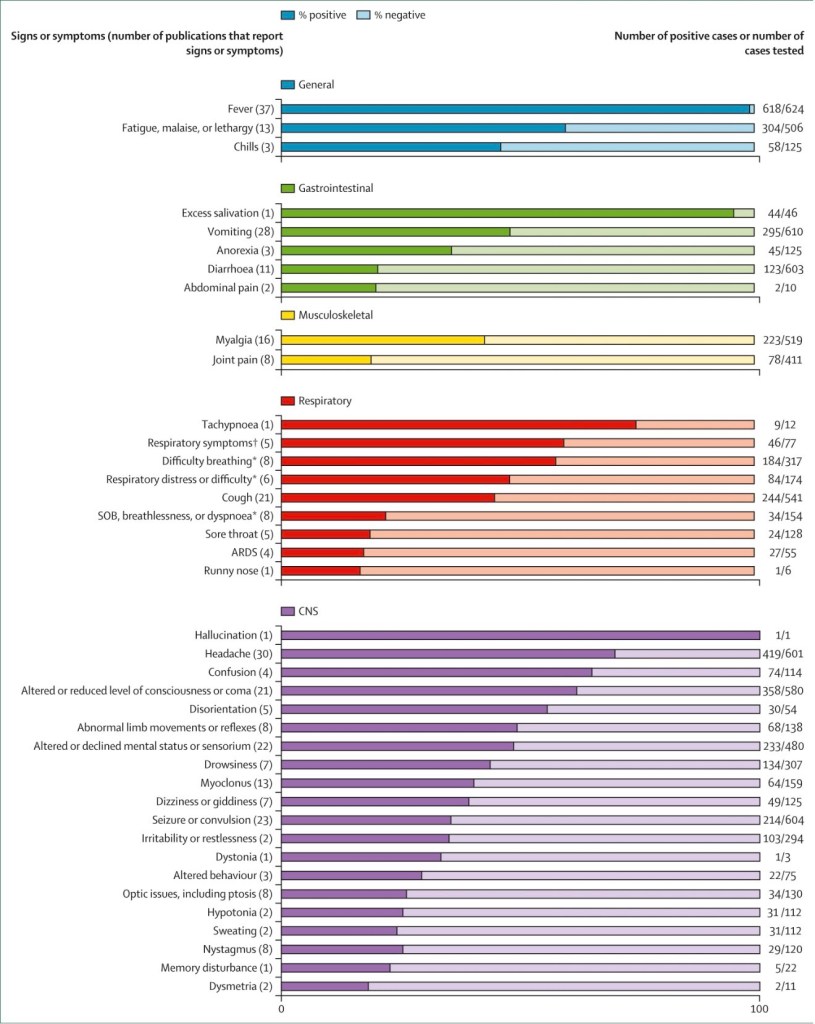

Nipah virus (NiV) is one of the deadliest zoonotic emerging pathogens (Soman Pillai et al., 2020). It is an enveloped virus that belongs to the Paramyxoviridae family and its genome consists of a single strand of RNA with negative polarity, about 18.2 kb long (Harcourt et al., 2000). Following an incubation period of less than two weeks, although it might vary from 4 days to two months (Aditi and Shariff, 2019), patients develop fever, headache, vomiting, respiratory distress, and encephalitis, manifested as seizure and unconsciousness (Ang et al., 2018). The NiV mortality rate ranges from 68% to 91% (Soman Pillai et al., 2020).

Fruit bats of the genus Pteropus (flying foxes) are the natural reservoirs for NiV (Halpin et al., 2011). NiV outbreak was first reported in 1998 in Sungai Nipah, a village in Malaysia, where humans contracted NiV from pigs, which in turn contracted the virus due to the consumption of fruits contaminated with saliva and excretes of fruit bats (Goh et al., 2000).

In pigs, this virus infects the respiratory system resulting in pneumonia with syncytial cells occurring in the vascular endothelium and in the respiratory epithelium at all levels of the lung. Disease is spread to human beings via the respiratory route. Human-to-human transmission of this virus has been reported in more recent outbreaks.

Recurring NiV outbreaks have then been reported in different parts of South Asia, including Bangladesh, where infections occurred due to the consumption of raw date palm sap contaminated with saliva and feces of the fruit bats (Soman Pillai et al., 2020). Foodborne transmission of NiV has also been demonstrated in laboratory animals (Kingsley, 2016). Interestingly, the orally administered virus in hamsters was detected in respiratory tissues rather than in the intestinal tract (Kingsley, 2016). Based on genetic diversity, two strains of NiV have been identified: NiV-B (Bangladesh) and NiV-M (Malaysia). NiV-B and NiV-M share 91.8% genetic similarity; however, NiV-B has higher fatality rates and is more prevalent (Mire et al., 2016). The attachment (G) and fusion (F) envelope glycoproteins are both required for viral entry into cells (Bradel-Tretheway et al., 2019).

It can cause encephalitis and pneumonia, and has a high case fatality rate.

Epidemiology

More than 250 people were affected with more than 100 deaths. It has caused subsequent outbreaks in Bangladesh from 2001 to 2004, and neighbouring West Bengal, India in 2001. Typically, there are a few dozen people affected each time. Nipah virus is related to Hendra virus, which caused disease in horses and their handlers in Australia in 1994 and in sporadic cases since then. The natural reservoir for Nipah virus is ‘flying fox’ fruit bats (genus Pteropus), with both virus detection and serological evidence for infection. Serological evidence of Nipah virus infection has subsequently been found in 23 species of bats from 10 genera in regions as widely spread as Yunan and Hainan Island in China, Cambodia, Thailand, India, Madagascar and Ghana in West Africa.

Clinical Features

Human infection with Nipah virus causes an encephalitis characterized by a reduced level of consciousness, myoclonus, areflexia and hypotonia. A smaller number of patients may present with atypical pneumonia with chest radiographs showing diffuse interstitial infiltrates. The incubation period ranges from 7 to 40 days. About one third of patients have meningism and generalized seizures occur in about 20%. Myoclonus typically involving the diaphragm, arms and neck is also seen. In addition there may be cerebellar dysfunction, tremors and areflexia. In more severe cases there is brainstem involvement, characterized by pinpoint, unreactive pupils, abnormal oculocephalic reflexes, tachycardia and hypertension.

Several reports have shown that patients who originally had mild or asymptomatic infections can present with encephalitis several months after the exposure. Clinically and immunologically these cases are reminiscent of sub-acute sclerosing panencephalitis caused by the paramyxovirus, measles virus. In the Malaysian outbreak, the mortality was approximately 35%, but in Bangladesh it has been more than 70%.

Diagnosis

There may be mild thrombocytopenia and elevated liver function tests. In the CSF, there is usually pleocytosis, with lymphocyte predominance. Because Nipah virus is a Biosafety level 4 pathogen, culture is not routinely attempted. The diagnosis is confirmed by IgM capture ELISA or PCR. MRI shows increased signal intensity in the cortical white matter. Typically there are small lesions in the subcortical and deep white matter, with surrounding oedema.

Management and Treatment

There is no treatment or vaccine, though ribavirin has been used in some cases. Because of the risk of nosocomial transmission, appropriate precautions should be taken, especially if patients are ventilated.

Prevention

There is no vaccine for Nipah virus. Preventive measures are aimed at stopping pig infection, human infection from infected animals and human-to-human transmission. Routine cleaning and disinfection of pig farms is thought to be important, as is animal surveillance – part of a ‘one health’ approach. Farmers need to be wary of the ‘barking pig’ with respiratory symptoms. If an outbreak in pigs is suspected, the animals should be culled and carcassesdisposed of, in a safe manner. Those handling sick animals should wear personal protective equipment.

Education of humans about the risk factors is important. In particular the need to boil freshly collected date-palm juice and to wash and peel fruit. Gloves and protective equipment should be worn when caring for people with suspected Nipah virus infection.

Nipah virus transmission occurs through several routes, with considerable attention focused on the consumption of raw date palm sap in regions where this practice is common. Bats, the natural reservoir of NiV, contaminate collection pots by licking the sap-producing surfaces of the date palms. This is considered the primary infection route in affected areas, leading to a seasonal pattern of outbreaks typically between January and May, coinciding with the sap collection period. Informational campaigns promoting the use of bamboo skirts on date palms to prevent bat contact have been implemented to mitigate this risk. Person-to-person transmission is another significant concern. Prevention measures include isolating infected or potentially infected individuals for 21 days and implementing robust surveillance and contact tracing systems. Healthcare workers should adhere to standard infection control protocols, including glove use, hand hygiene, and appropriate personal protective equipment.

Medical News

At the moment, there’s a deadly outbreak in the state of West Bengal with 5 confirmed cases. VV116 is an antiviral drug that was approved for treating COVID in China and Uzbekistan. It was developed by researchers at the Wuhan Institute of Virology and other institutes, the researchers that have run the COVID study for testing the drug’s efficacy has also published a paper on the nipah virus and stated that it could be used on patients with a high fatality rate and higher risk individuals (medical professionals). Its already qualified for human testing.

Potential therapeutic candidates for NiVD that are currently progressing through the research and development pipeline include monoclonal antibodies and small molecule antivirals. Current animal model data support potential in-human trial for m102.4, Hu1F5, and remdesivir, either alone or in combination. Phase 1 safety data for m102.4 are available from an Australian trial; however, further development of m102.4 has not progressed, because the more potent Hu1F5 has shown superior efficacy in non-human primate models and is now advancing to phase 1 evaluation in the USA. These potential new and repurposed treatments will need to be evaluated for safety and efficacy in clinical trials.

Sources:

https://www.mdpi.com/2076-2607/13/1/124

https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/immunology-and-microbiology/nipah-virus

2014, Manson’s Tropical Infectious Diseases (Twenty-third Edition)

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/chapter/monograph/pii/B9780128008386000217#s0035

https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lanmic/article/PIIS2666-5247(25)00223-X/fulltext