“An enemy fighter chopped off our commander’s arm with a large knife (khukuri). I was the only militia with medical knowledge and with some drugs there. Immediately I put on a bandage on his arm and provided medication to him. It was my first war health experience and perhaps this was the first treatment a Maoist health worker had provided.”

Interviewee 3

During the conflict, the first author conducted a study of the Maoist Health Workers as part of his PhD thesis in the period 2007 to 2010.

There was once a health paradox in Nepal’s violent conflict. This conflict lasted a decade in Nepal from 1996 to 2005. Around 13,000-14,000 people where killed directly. Thousands disappeared, or were kidnapped, prosecuted, tortured, injured and disabled. Despite these war deaths, the period of insurgency appears to be associated with an increase in the overall health status of the people in Nepal as measured by a range of health outcomes.

This chapter is largely derived from the data collected for the PhD study by the first author. The study used a mixed-methods approach; the quantitative part involved 15 interviews with Maoist health workers in 2007-2008 and the quantitative part involved a questionnaire-based study with 197 Maoist healthcare workers. Many interviewees had been working as rebel health workers largely underground in remote areas and provisional camps, and some were working in, or managing the operations of, primary health centres in areas controlled by the Maoists. The study received ethical approval from the Nepal Health Research Council and the Health Division of the CPN-M, and All Nepal Public Health Worker’s Association (ANPHWA)-Maoist sister wing, granted access to their health workers.

The 10-year long armed conflict between the Maoist rebels and the Government of Nepal started in 1996 and formally ended in 2006. The insurgency is often referred to as ‘The People’s War’ or janayuddha. The uprising was launched by the then Communist Party of Nepal-Maoist (CPN-M), and the Maoist rebels gained control over quite all large area of Nepal, mainly in the more remote and rural parts of the country. Over the early years of the millennium, the conflict escalated, as some have argued not because Nepalis necessarily wanted a communist rule, but because they wanted to end a centuries old social and political system that favour a very small elite and excluded most ordinary citizens.

Like any other army, once the fighting with government forces started, the Maoist rebels needed a way of getting emergency healthcare for their wounded soldiers. The rebels incorporated paramedics in combat groups of self-defence groups in the villages, whose main aim was to provide first aid during and after combat. Estimates of the number of Maoist rebel health workers range from 1000 to 1500. These are Nepalis who were either pharmacists, doctors or paramedics performing duty on the field in their work-skill.

A key member of the Maoist Central Health Division suggested there existed 900-1000 health workers who were trained and participated in the People’s War. Vibhishikha (2009) also suggests that the number of health workers was closer to 1,500. Being an organised political movement with links with Maoist rebel groups elsewhere, especially in India, the rebels had some preparation for this. The proportion of female rebel health workers was at 40% and was higher than the proportion of female rebel soldiers which was at 33%. The Maoist rebellion generally attracted members of more disadvantaged groups and a significant number of women and youth. Many seemed to be concerned about their subordinate role in traditional Nepali Society; it appears the Maoists offered them the kind of political support and freedom associated with modern society.

At the same time, the Maoists used alternative approaches to getting medical treatment for battlefield casualties. This included smuggling wounded comrades to India for medical treatment. The Maoists also took some wounded rebels away from the areas of fighting to get treatment in hospitals in Kathmandu, seeking treatment from ideologically sympathetic healthcare workers in government hospitals, as well as establishing their own healthcare service.

When it became clear that more healthcare workers were needed to enable the rebels to support a greater number of fighters and control larger local areas, formal training was introduced. Using their organisational strength, the Maoists set up their own healthcare systems which included a training program with several curricula at different levels of competencies and its own training manuals. However, systematic training of rebel health workers only seemed to have started with the establishment of their training centre in 2002.

During the conflict, the Maoists developed separate training curricula to train four levels of ‘model health workers’: Ordinary (O), Medium (M), Standard (S), and Advanced (A). They call it collectively OMSA. Each of these training levels required training of 30 to 45 days, including field practical. The majority of rebel health workers was trained by Maoists to the basic level O. The training period does not seem compatible with the skills prescribed for lower level government health staff. However, on closer analysis, the contents of the Maoist health worker training packages did not differ much from the government’s syllabi. The Maoist health workers had often participated in small amounts of training provided by foreign ‘doctors’.

The Maoist workers claim that they have learnt many skills through practice, particularly on the battlefield. They were mostly trained by Nepali trainers but some medically trained foreigners were also involved. The Maoist health workers self report that they possess important skills such as triaging, dressings of wounds, lifesaving skills, treatment of fractures and minor improvised surgeries and amputations. They also report that they prescribe and dispense essential drugs. They claim they have both theoretical and practical experiences and are competent to deliver basic healthcare services as community or support level health workers.

(ps Nepal I’m usually disappointed in you as a country but in the context of this true story I’m actually impressed! I’m looking forward to covering more crazy stories like these! Just so you know I’m really difficult to impress! I applaud you for this matter!)

Source:

The Dynamics of Health in Nepal

Chapter 7

Exploring Rebel Health Services during the Maoist People’s War

Bhimsen Devkota & Edwin van Teijlingen

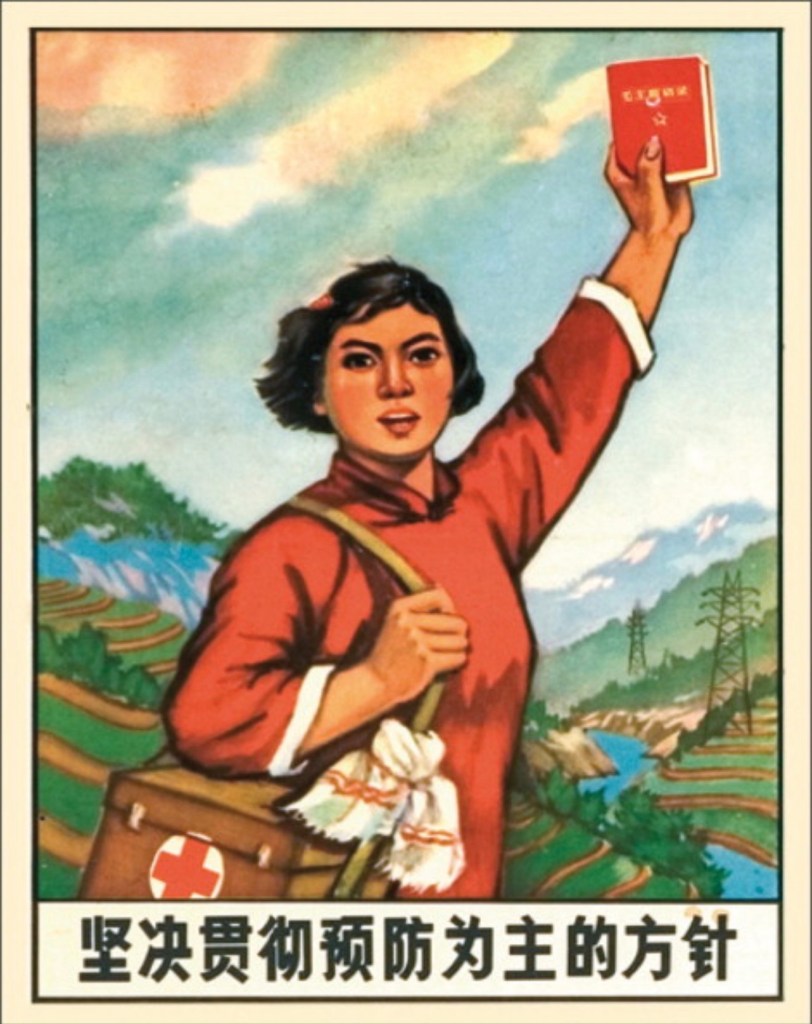

https://www.nlm.nih.gov/hmd/chineseposters/public.html

Image Credit: https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140673608616104/fulltext