Imagine a billionaire that’s a tech giant having a vision to fulfil, it may bring chaos, violence, and intense human emotions but it also brings a huge lump sum of cash! Your child is one of the few chosen ones to go on a far-away realm in the palms of their hands, it’s Mars! It’s incredibly revolutionary but that is a problem too!

As the child grows up on Mars, their bodies become permanently tailored to it. What legal limits have we imposed on these tech companies so far? In the United States, which ended up setting the norms for most other countries, the main prohibition is the Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act (COPPA), enacted in 1998. It requires children under 13 to get parental consent before they can sign a contract with a company (the terms of service) to give away their data and some of their rights when they open an account. That set the effective age of “internet adulthood” at 13, for reasons that had little to do with children’s safety or mental health. But the wording of the law doesn’t require companies to verify ages, as long as a child checks a box to assert she’s old enough, she can go almost anywhere on the internet without parents’ knowledge or consent.

While the reward seeking parts of the brain mature earlier, the frontal cortex essential for self-control, delay of gratification, and resistance to temptation—is not up to full capacity until the mid-20s, and preteens are at a particularly vulnerable point in development. As they begin puberty, they are often socially insecure, easily swayed by peer pressure, and easily lured by any activity that seems to offer social validation. We don’t let preteens buy tobacco or alcohol, or enter casinos. The costs of using social media in particular are high for adolescents. Let children grow up on Earth first, before sending them to Mars.

This is how age will be categorised in the rest of this book:

• Children: 0 through 12

• Adolescents: 10 through 20

• Teens: 13 through 19

• Minors: Everyone who is under 18.

The author is a social psychologist not a clinical psychologist or a media studies professional. The studies and theories represented throughout the course of the book however, are from various subjects like clinical studies with evidence, psychology, clinical psychology and psychiatry as well.

There was little sign of an impending mental illness crisis among adolescents in the 2000s. Then, quite suddenly, in the early 2010s, things changed. Each case of mental illness has many causes; there is always a complex backstory involving genes, childhood experiences, and sociological factors. My focus is on why the rates of mental illness went up in so many countries between 2010 and 2015 for Gen Z and some late millennials while older generations were much less affected. Why was there a synchronised international increase in rates of adolescent anxiety and depression?

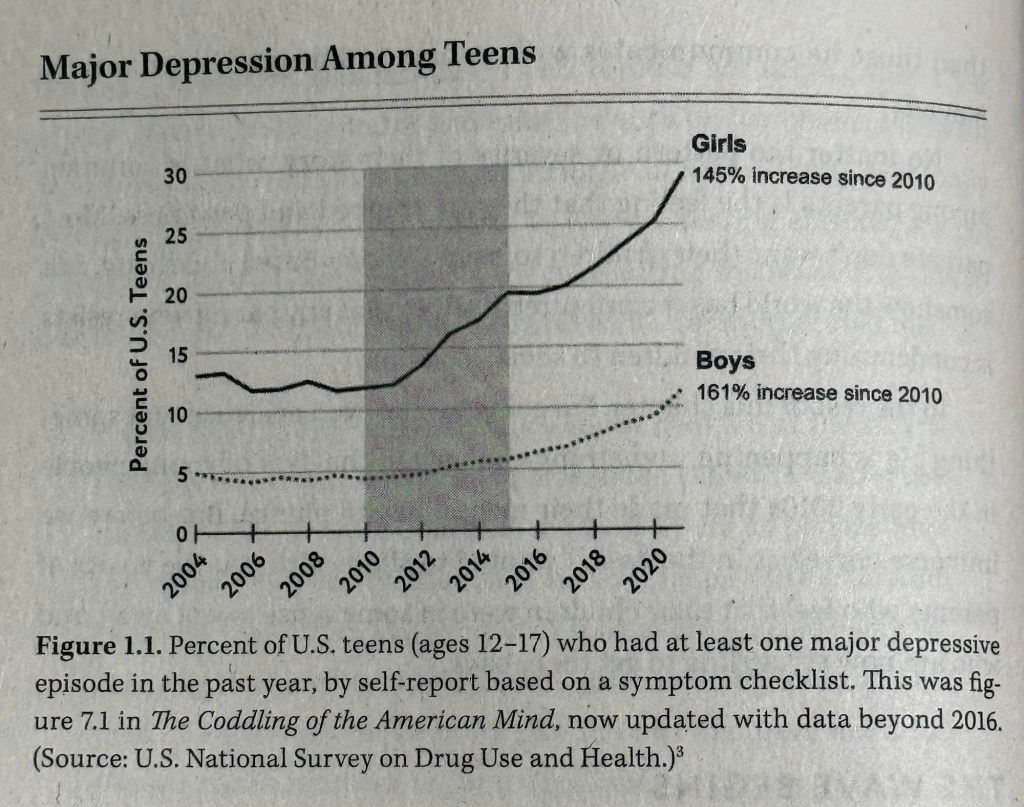

In a survey conducted every year by the U.S. government, teens are asked a series of questions about their drug use, along with a few questions about their mental health. Those who answered yes to more than five out of the nine questions about symptoms of major depression are classified as being highly likely to have suffered from a “major depressive episode” in the past year. You can see a very large upturn in major depressive episodes, beginning around 2012.

Depression became roughly two and a half times more prevalent.

What on earth happened to these teens in the early 2010s?

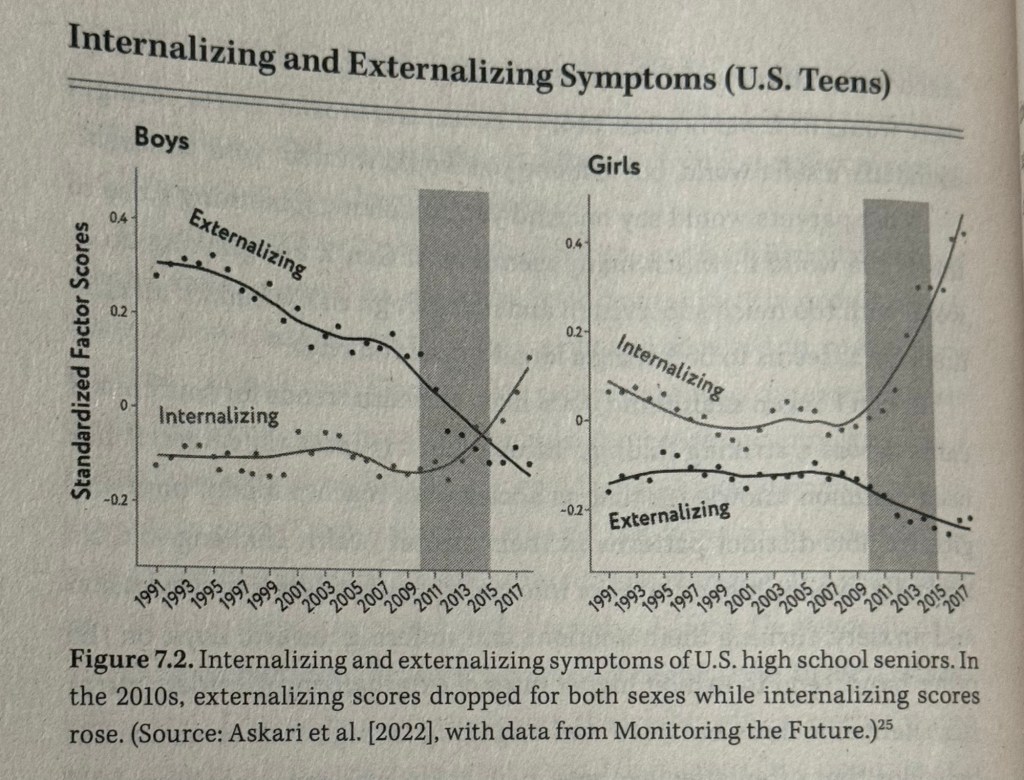

We found important clues to this mystery by digging into more data on adolescent mental health. The first clue is that the rise is concentrated in disorders related to anxiety and depression, which are classed together in the psychiatric category known as internalising disorders. These are disorders in which a person feels strong distress and experiences symptoms inwardly. The person with an internalising disorder feels emotions such as anxiety, fear, sadness, and hopelessness. They ruminate. They often withdraw from social engagement.

In contrast, externalising disorders are those in which a person feels distress and turns the symptoms and responses outward, aimed at other people. These conditions include conduct disorder, difficulty with anger management, and tendencies toward violence and excessive risk-taking. Across ages, cultures, and countries, girls and women suffer higher rates of internalising disorders, while boys and men suffer from higher rates of externalising disorders. That said, both sexes suffer from both, and both sexes have been experiencing more internalising disorders and fewer externalising disorders since the early 2010s.

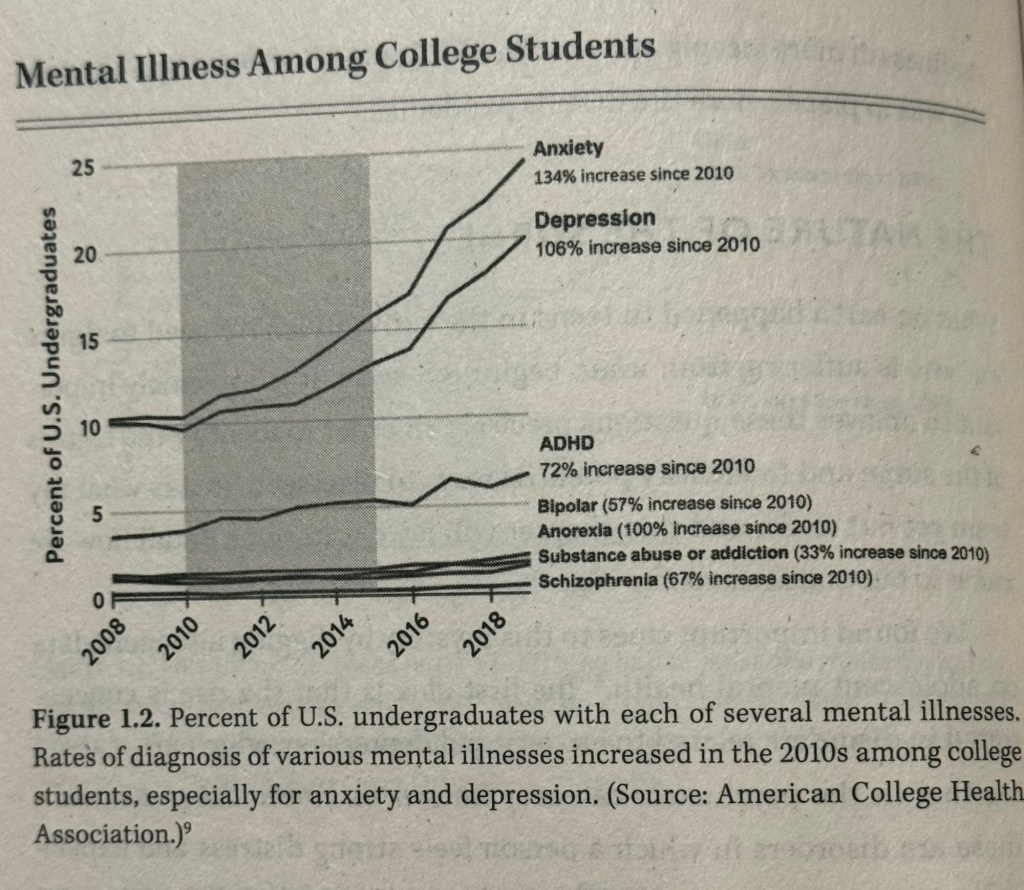

You can see the ballooning rates of internalising disorders in figure 1.2, which shows the percentage of college students who said that they had received various diagnoses from a professional. The data comes from a standardised survey from universities, aggregated by the American College Health Association. The lines for depression and anxiety start out much higher than all other diagnoses and then increase more than any other in both relative and absolute terms. Nearly all of the increases in mental illness on any college campuses in 2010s came from increases in anxiety and/or depression.

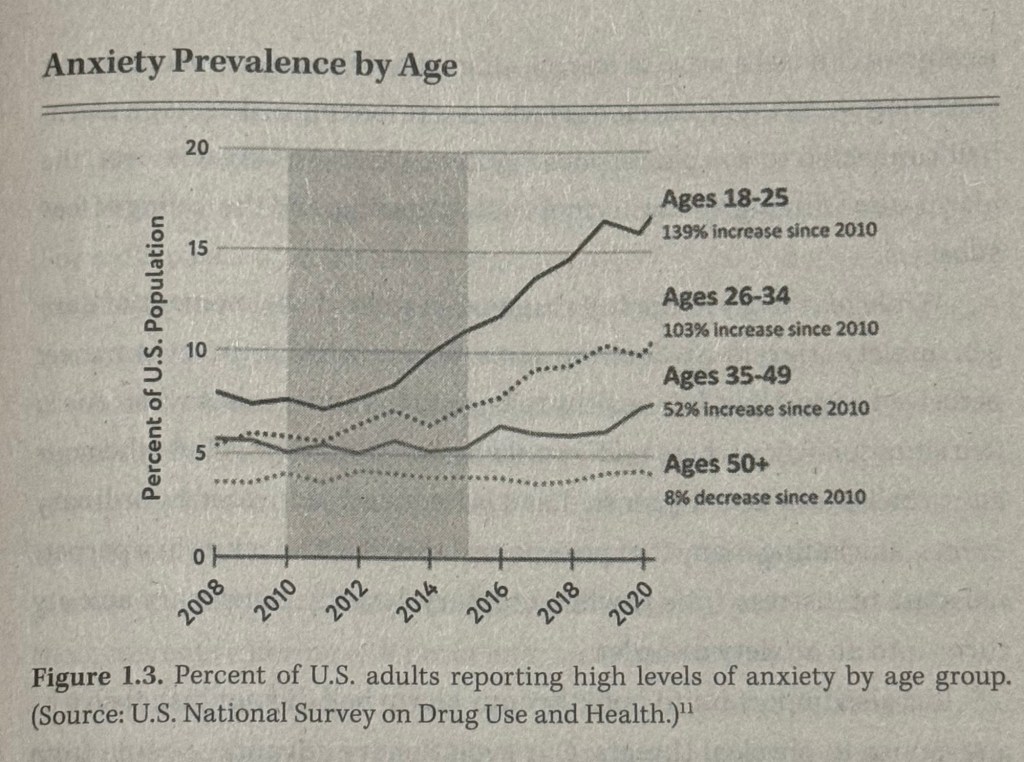

A second clue is that the surge is concentrated in Gen Z, with some spillover to younger millennials. You can see this in Fig 1.3, which shows the percentage of respondents in four age-groups who reported feeling nervous in the past month “most of the time” or “all of the time.” There is no trend in any of the four age-groups before 2012, but then the youngest age group starts to rise sharply. The next older age-group rises too, though not as much, and the two oldest age groups are relatively flat: a slight rise for Gen Z and a slight decrease for baby boomers.

Across a variety of mental health diagnoses, you can see that anxiety rates rose most in figure 1.2, with depression following closely behind. A 2022 study of more than 37,000 high school students in Wisconsin found an increase in the prevalence of anxiety from 34% in 2012 to 44% in 2018, with larger increases among girls and LGBTQ teens. A 2023 study of American college students found that 37% reported feeling anxious “always” or “most of the time.” This means that only one third of college students said they feel anxiety less than half the time or never.

The second most common psychological disorder among younger people today is depression, as you can see in figure 1.2. The main psychiatric category here is called major depressive disorder (MDD). It’s two key symptoms are depressed mood and a list of interest or pleasure in most or all activities. For a diagnosis of MDD, these symptoms must be consistently present for at least two weeks.

The day after we published The Coddling of the American Mind, an essay appeared in The New York Times with the headline “The Big Myth About Teenage Anxiety.” In it, a psychiatrist raised several important objections to what he saw as a rising moral panic around teens and smartphones. He pointed out that most of the studies showing a rise in mental illness were based on “self-reports,” like the data in fig 1.2. A change in self-reports does not necessarily mean that there is a change in underlying rates of mental illness.

Perhaps young people’s just became more willing to talk honestly about their symptoms? Or perhaps they started till mistake mild symptoms of anxiety for a mental disorder? Was the psychiatrist right to be skeptical? He was certainly right that we need to look at multiple indicators to know if mental illness really is increasing.

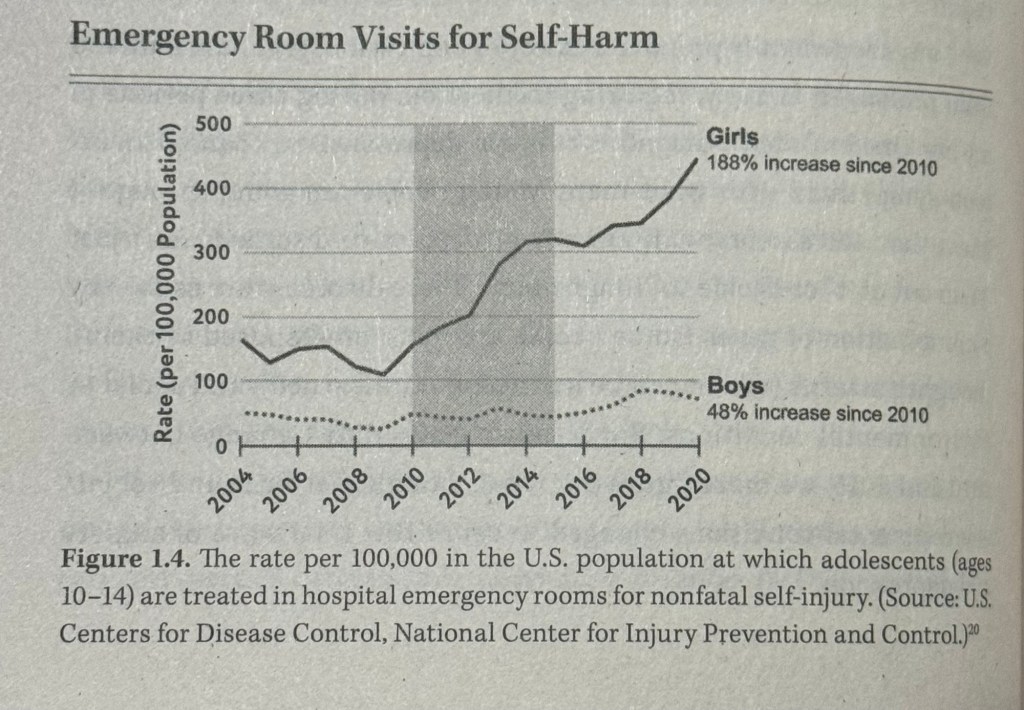

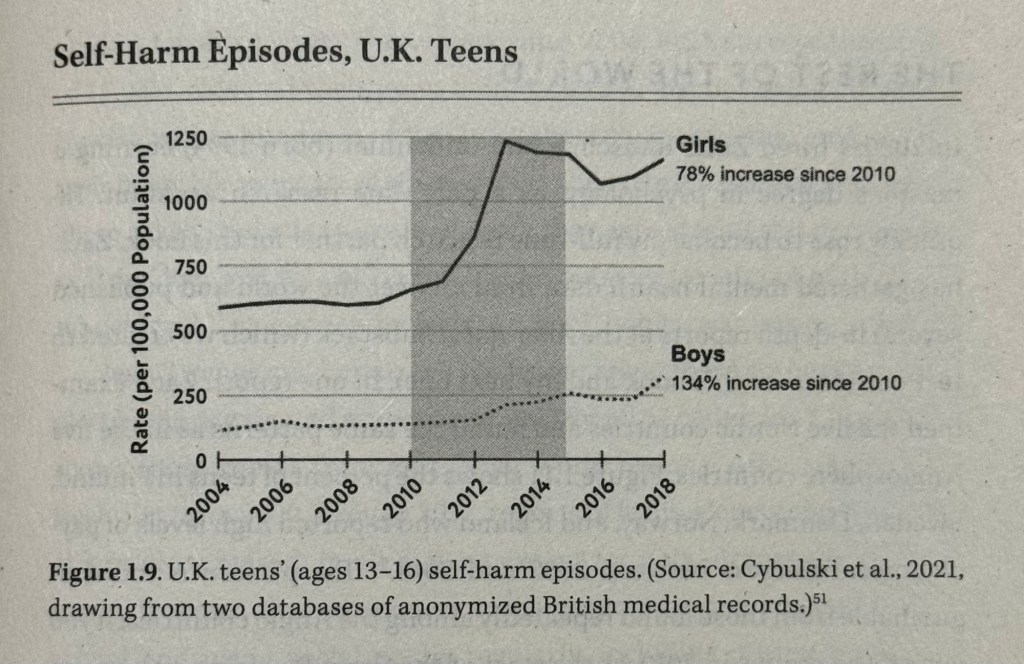

The rate of self-harm for these young adolescent girls nearly tripled from 2010 to 2020. The rate for older girls (ages 15-19) doubled, while the rate for women over 24 actually went down during that time. So whatever happened in the early 2010s, it hit preteen and young teens harder than any other group. This is a major clue. Acts of intentional self-harm in fig 1.4 include both non fatal suicide attempts, which indicate very high levels of distress and hopelessness, and NSSI, such as cutting. The latter are better understood as coping behaviour that some people use to manage debilitating anxiety and depression.

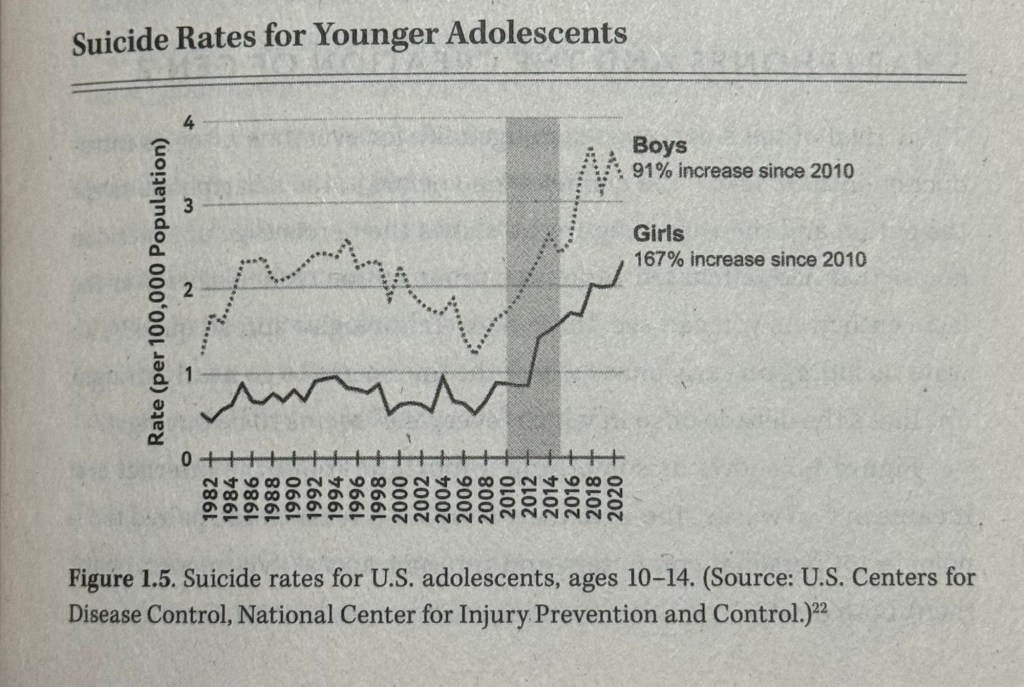

Adolescent suicide in the United States shows a time trend generally similar to depression, anxiety, and self-harm, although the period of rapid increase begins a few years earlier. Fig 1.5 shows the suicide rate, expressed as the number of children aged 10-14, per 100,000 such children in the US population, who died by suicide each year. For suicide the rates are nearly always higher for boys than for girls in Western nations, while attempted suicides and non-suicidal self-harm are higher for girls, as we saw above.

Fig 1.5 shows that the suicide rate for young adolescent girls began to rise in 2008, with a surge in 2012, after having bounced around within a limited range since the 1980s. From 2010 to 2021, the rate increased 167%. This too is a clue guiding us to ask: What changed for pre teen and younger teen girls in the early 2010s?

This offers a strong rebuttal to those who were skeptical about the existence of a mental health crisis. The pairing of self-reported suffering with behavioural changes tells us that something big changed in the lives of adolescents in the early 2010s perhaps beginning in the late 2000s.

The arrival of the smartphone changed life for everyone after its introduction in 2007. Like radio and television before it, the smartphone swept the nation and the world. Figure 1.6 shows the percentage of American homes that had purchased various communication technologies over the last century. As you can see, these new technologies spread quickly, always including an early phase where the line seems to go nearly straight up. That’s the decade or so in which “everyone” seems to be buying it.

Figure 1.6 shows us something important about the internet era: It came in two waves. The 1990s saw a rapid increase in the paired technologies of personal computers and internet access (via modern, back then), both of which could be found in most homes by 2001. Over the next 10 years, there was no decline in teen mental health. Millennial teens, who grew up playing in that first wave, were slightly happier, on average, than Gen X had been when they were teens. The second wave was the rapid increase in paired technologies of social media and the smartphone, which reached the majority of homes by 2012 or 2013. That is when girls’ mental health began to collapse, and when boys health began to change in a more diffuse set of ways. Of course, teens had cell phones since the late 1990s but they were “basic phones with no internet access-flip phones if you will.

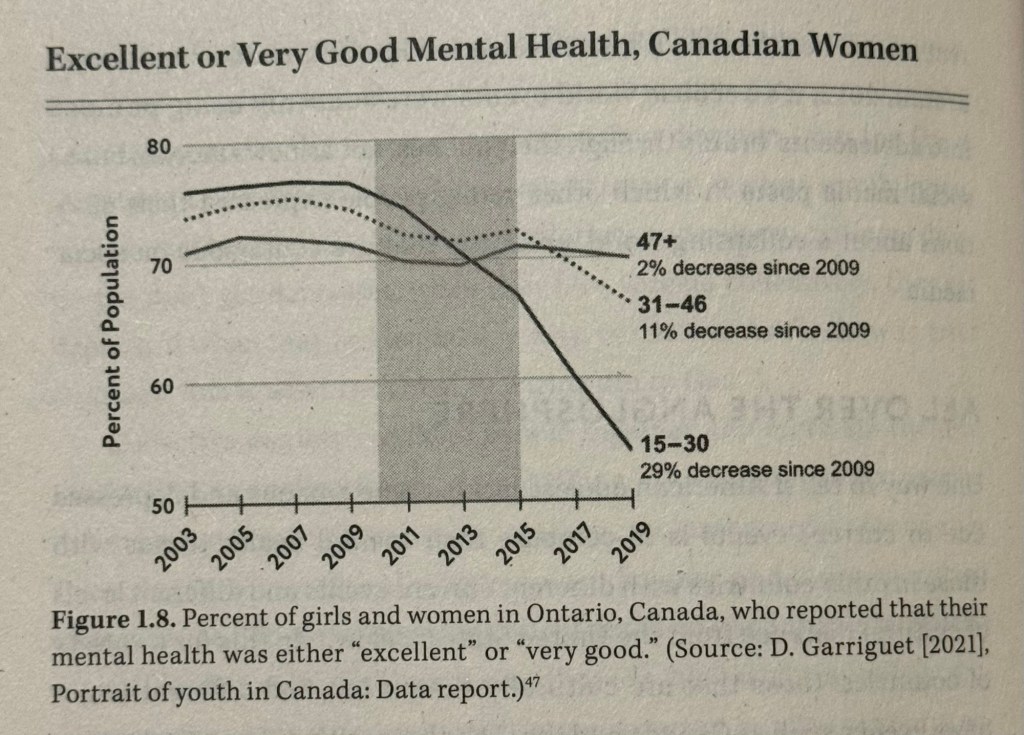

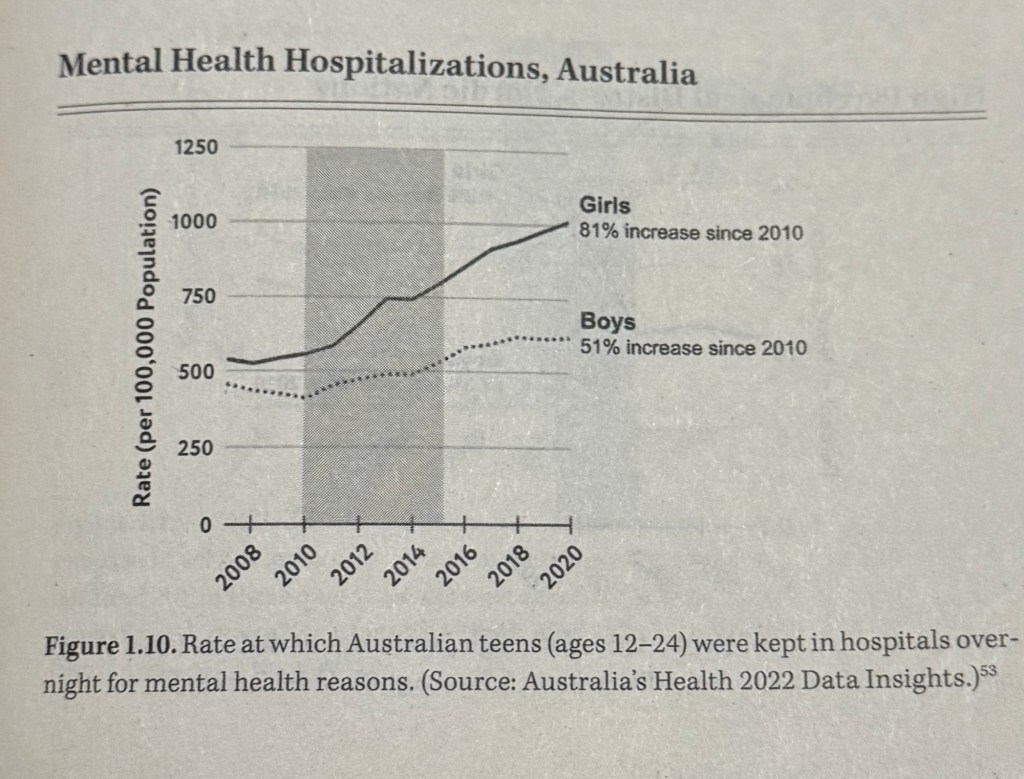

Figure 1.8 shows the percent of Canadian girls and women who reported that their mental health was either “excellent” or “very good.” If you stopped collecting data in 2009, you’d conclude that the youngest group (aged 15-30) was the happiest, and you’d see no reason for concern. But in 2011 the line for the youngest women began to dip and then went into free fall while the line for the oldest group of women (aged 47 and up) didn’t budge. The graph for men and boys shows the same pattern, though with a smaller decline. As in the United States and Canada, something seems to have happened to British teens in the early 2010s that caused a sudden and large increase in the number of teens harming themselves. We see similar trends in the other major Anglo-sphere nations including Ireland, New Zealand and Australia.

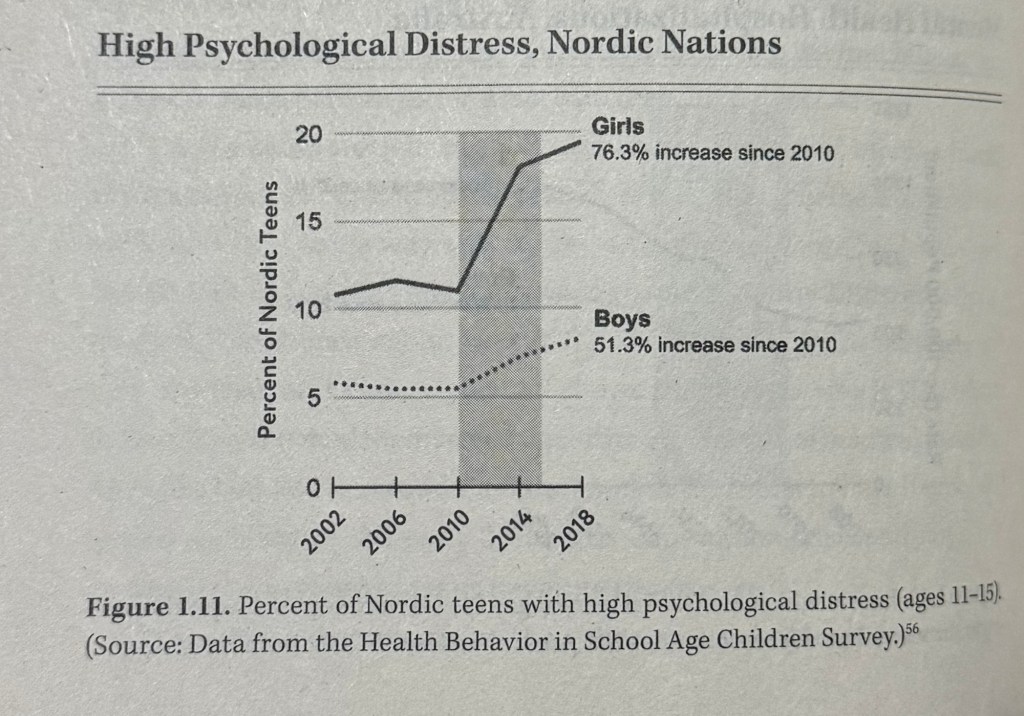

Figure 1.11 shows the percent of teens in Finland, Sweden, Denmark, Norway, and Iceland who reported high levels of psychological distress between 2002 and 2018.

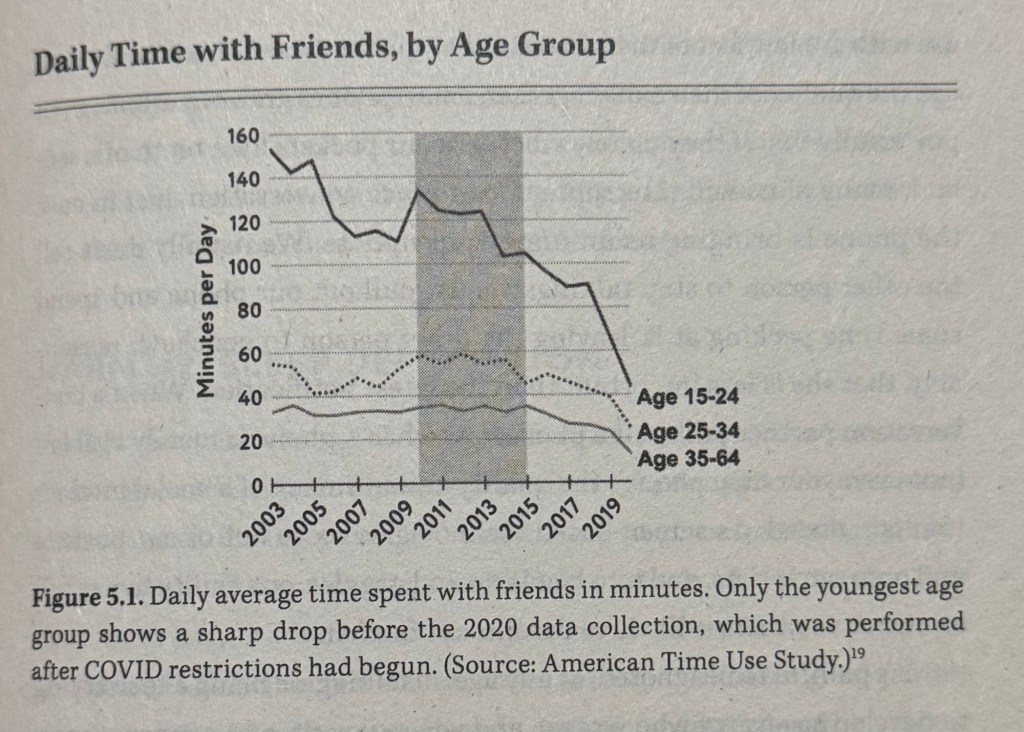

You can see the loss of friend time in finer detail in fig 5.1, from a study on how Americans of all ages spend their time. The figure shows the daily average number of minutes that people in different age brackets spend with their friends. Not surprisingly, the youngest group spend more time with friends, compared with the older groups who are most likely to be employed and married. The difference was very large in the early 2000s, but it was declining, and the decline accelerated after 2013. The data for 2020 was collected after the COVID pandemic arrived, which explains why the line bends downward in the last year for the two older groups.

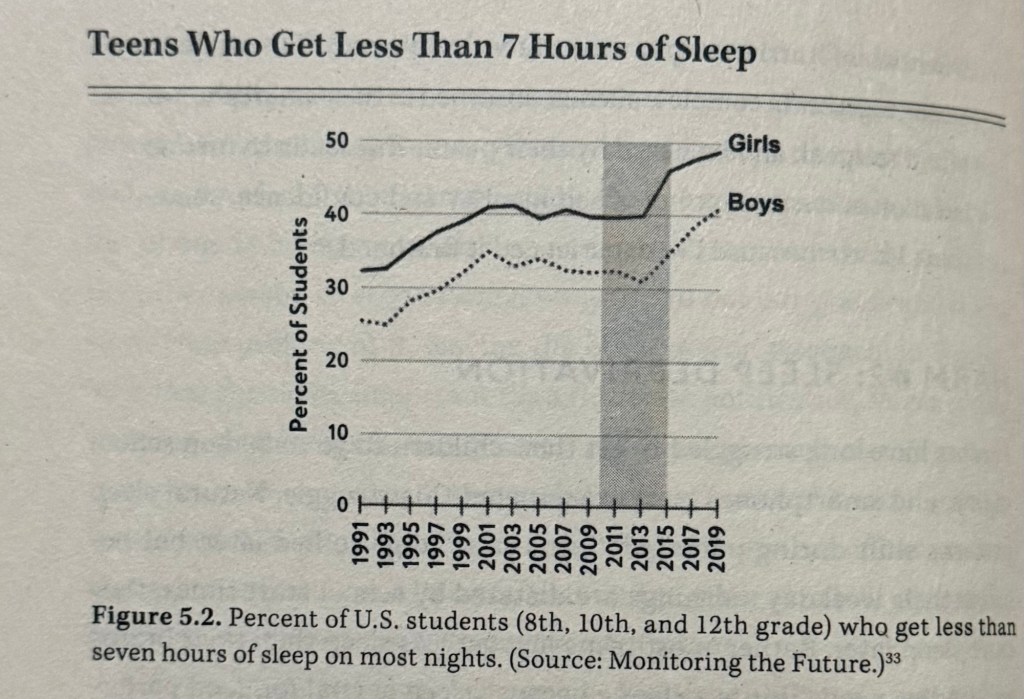

Teens need more sleep than adults—atleast nine hours a night for preteens and eight hours a night for teens. Back in 2001, a leading sleep expert wrote that “almost all teenagers, as they reach puberty, become walking zombies because they are getting far too little sleep.” When he wrote that sleep deprivation had been rising for a decade, as you can see in fig 5.2. Sleep deprivation then levelled off through the early 2010s. After 2013, it resumed its upward match.

A Dutch longitudinal study found that young people who engaged in more addictive social media use at one measurement time had stronger ADHD symptoms at the next measurement time. Another study by a different group of Dutch researchers used a similar design and also found evidence suggesting that heavy media multitasking caused later attention problems but they found this casual effect only among younger adolescents aged 11-13 and it was especially strong for girls.

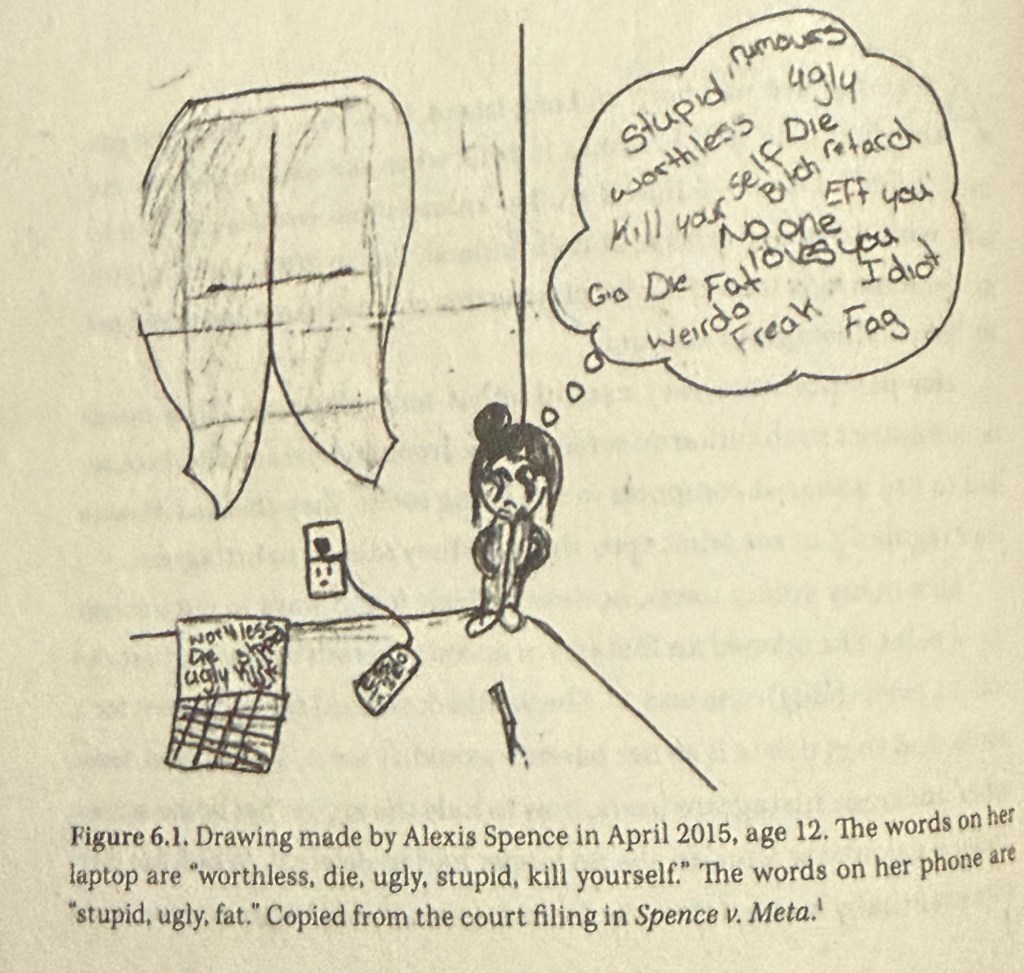

Spence vs Meta

Alexis Spence was born on Long Island, New York, in 2002. She got her first ipad for Christmas in 2012, when she was 10. Initially she used it for Webkinz—a line of stuffed animals that enables children to play with a virtual version of their animal. But in 2013, while in fifth grade, some kids teased her for playing this childish game and urged her to open an Instagram account. Her parents wer very careful about technology use. There were strict prohibitions on screens in bedrooms, she and her brother had to use a shared computer in the living room. They checked her ipad regularly and said no to Instagram.

She found a way to open an instagram account saying she’s 13 even though she was 11. She would download the app for a while and delete it before her parents could see it. She had learned from other underage Instagram users how to hide the app on her home screen. When her parents found out and put restrictions in place, she made secondary accounts. At first she was elated with Instagram but over the next months her mental health plunged. Five months after her Instagram account was created she drew the picture below.

In eighth grade, she was hospitalised for anorexia and depression. She battled eating disorders and depression for the rest of her teen years. Alexis is now 21 and had regained control of her life. She works as an emergency medical technician and still struggles with eating disorders.

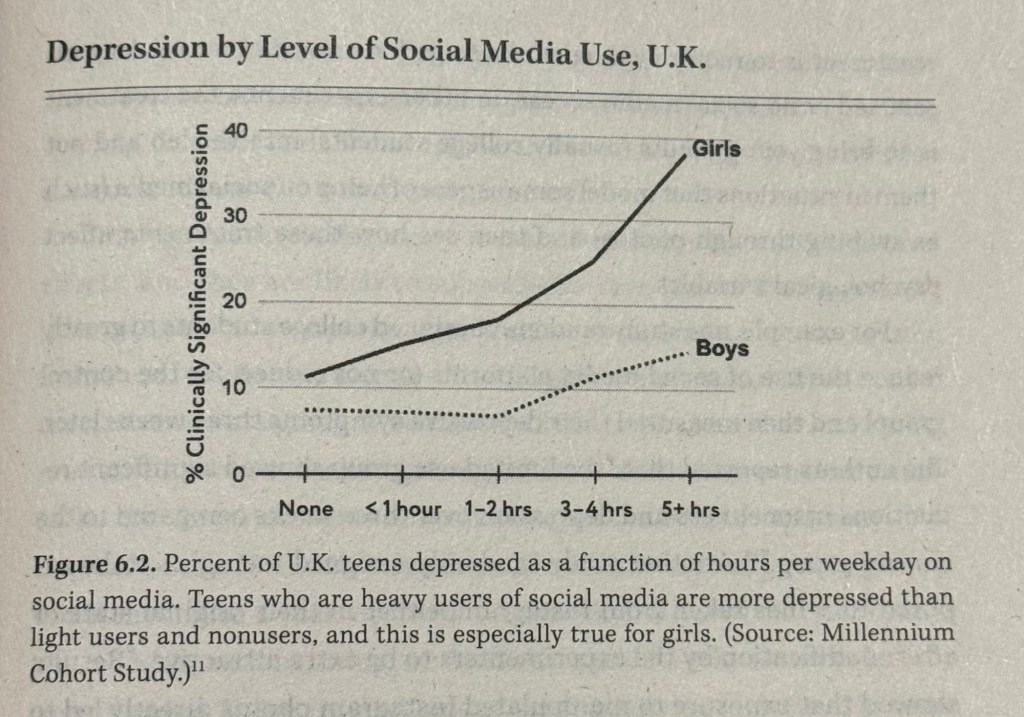

You can see this sizeable link in fig 6.2, which reports data from the Millennium Cohort Study, a British study followed roughly 19,000 children born around the year 2000 as they matured through adolescence. The figure shows the percentage. The figure shows the percentage of UK teens who could be considered depressed as a function of how many hours they reported spending on social media on a typical weekday. It’s only when boys are spending more than 2 hours per day that the curve begins to rise.

Remember internalising and externalising!

(ps feel free to go crazy with me over these graphs! 🤪)

The author’s continuing of the book series:

Source:

The Anxious Generation- Jonathan Haidt