Where there’s war, there’s wounds, when there are wounded people and militia there’s the dire need for a doctor.

Brotherhood was a mass language that was fuelled by the consciousness and the reasoning of religion and faith. Being brothers meant looking out for each other without any established boundaries, caring for each other even when sick with leprosy, and attending and praying for the deceased. Anyone could be your brother, it could be a pilgrim or a fellow military monk that rose through the ranks. There was a social harmony and balance like no other. Money played a big role and was a big deal but it also gave birth to how hospitals worked back then and why they were needed.

Kings favoured these pacts that they would grant these orders but this is solely because they pioneered setting up hospitals for Christian pilgrims and this provided them with recovery on their trip to Jerusalem. Budgeting for a treatment under the orders were sometimes what stood between life and death. The poor were no exception to receiving medical aid either. Reconstructing destroyed villages, towns and vineyards and fighting were just a small part and the most widely anticipated but what if I told you straight up that providing care to the destitute and sick was one of their primary objectives and what gave them a bit more than what most people would get for pocket money at that time?

The Dominican friars perhaps had the most advanced regulations regarding infirmary practices; the Cistercians, along with the rest of the Benedictines, emphasized religious ceremonies for the spiritual welfare of the feeble; and the Augustinians were particularly concerned to restrict medical assistance to the truly sick. The rather common dietary laws, one has to believe, were based on the Salerni-tan Regimen, which was in turn in great part a composite of Hippocratic, Galenic and Arab ideas. Phlebotomy was a commonly accepted treatment in the West as well as in the East, whereas surgery seemingly was more tolerated by the Rule of St. Basil than by the Catholic Church. The Eastern monastic rule, no doubt, had some influence on Byzantine monastic life, including care of the sick. Keeping in mind the fact that most of the Western knights passed through Constantinople on their way to the Holy Land, it is rather enticing to look at medical treatment in the imperial city The best information on Byzantine medicine in the first century of the Crusades can be derived from regulations on the care of sick monks in the Constantinopolitan monastery of Pantocrator (the Almighty), founded in 1136 by Emperor John Il Comnenus. According to his regulations, the slightly sick monks received daily attention in their cells from a doctor who also decided what care was needed to restore their health. The more seriously ill monks had to go to the infirmary where six beds were kept ready at all times to receive the sick; there they were attended by a physician who ordered the needed treatment and medicine. If necessary, the doctor even remained close to the sick in a special bed. The sick were given better food including bread and wine, and were excused from religious exercises and fasting; bathing was allowed with the permission of the physician.

More complex than in the Byzantine Empire is the role of physicians in the crusader states and in the military orders in particular, for with the fall of Acre in 1291 the archives of the military orders in the Holy Land also perished. Thus, the best source available is again their statutes which, as indicated above, make no mention of brother doctors: the person in actual charge of the sick brothers was the infirmarian, himself a brother knight (TN Rule 6, 24, Customs 8; T 61, 190, 196; H 1262:3039.37, H 1304:4672.11).

Usually medical doctors serving the sick brothers were not members of a religious community but outside practitioners. Their learning and methods of healing were fundamentally based on Greek and Arabic authorities to whom references were repeatedly made; by the time of the Crusades, and particularly during the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, the opinions of these authorities had become common knowledge in the West as well as in the crusader states.

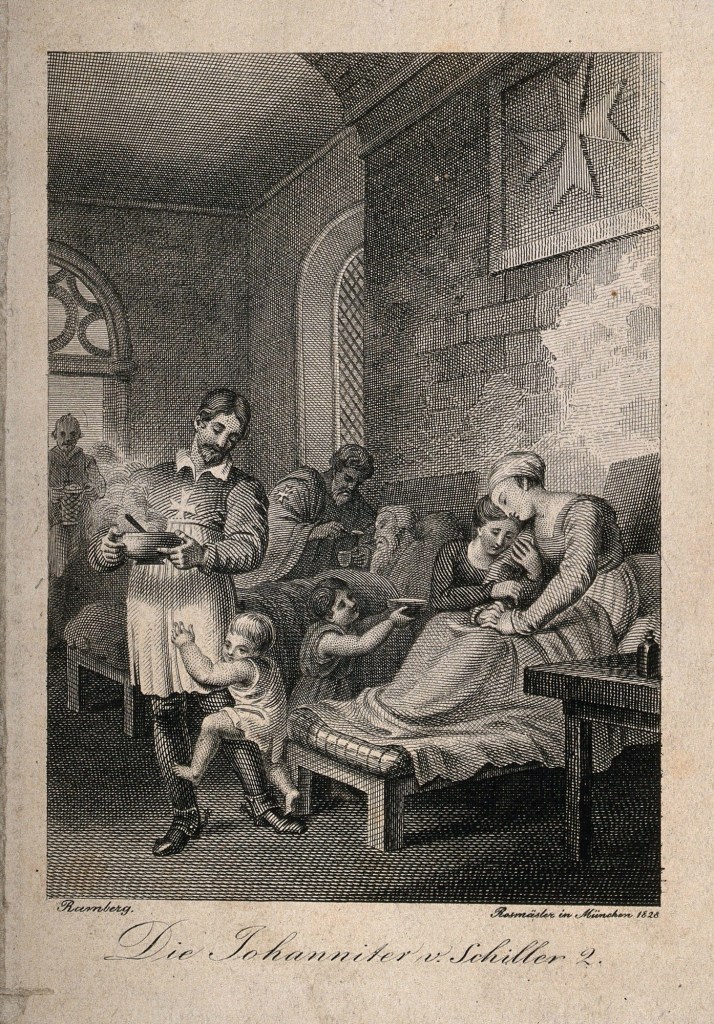

Three major military religious orders were founded in the Holy Land during the Crusades. Of these, two, as their names indicate, were originally hospitals established for the care of the poor and sick among Western pilgrims who travelled to Palestine to visit the holy places. One was the Order of the Hospital of St. John of Jerusalem, more frequently referred to as the Knights Hospitallers, and the other, which was the youngest and the least renowned of the triad, was the Order of the German Hospital of St. Mary in Jerusalem, or the Teutonic Knights. The third order, of course, was the Order of the Temple, or the Knights Templars.

With the establishment of the Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem in 1099,9 the Christians were faced with the problem of protecting the hordes of pilgrims arriving in the Holy Land. To deal with that situation, a knight from Cham-pagne, Hugh of Payens, together with a certain Godfrey of St. Omer and six other knights, decided to band together to protect pilgrims on their way from the port of Jaffa to Jerusalem. In 1118 King Baldwin I turned over lodgings in the area of the Temple to these knights, where they settled and became known to their contemporaries as the Poor Knights of the Temple.’

The Knights Templars first appeared in battle in support of the Kingdom of Jerusalem against the infidels in 1129 when they took part in the abortive expedition of King Baldwin Il against Damascus.12 Not so clear is the origin of the military activities of the Knights Hospitallers. The first trustworthy evidence of their military duties can be traced to the year 1136, when King Fulk entrusted them with the defense of the castle of Bethgiblin in southern Palestine; this indicates that they had had some military organization and capabilities before this date. As has been noted, the brethren-at-arms are first mentioned in 1182.13

The third military order, the Teutonic Knights, is linked by tradition with German hospitals in Jerusalem and in Acre. There is no official document extant about the establishment of the Teutonic Order, but the clearest narrative about a German hospital in Jerusalem is that of James of Vitry, bishop of Acre (1216-1228).’* James wrote an account of German pilgrimages to Jerusalem in the early twelfth century in which he states that after the conquest of Jerusalem in 1099 by the crusaders, many Germans went to the Holy City as pilgrims, but only a few of them knew Latin or Arabic. There-fore, a German couple who lived in the city built with their own means a hospital for the care and housing of poor and sick Germans, as well as a chapel dedicated to the Virgin Mary. The German couple seems to have maintained the establishment from their own wealth and also from alms, for many Germans gave money to support the hospital and even forsook worldly occupations in order to care for the sick. 15

The basic sources of information on the medical work of the three orders are their respective statutes, compiled in the Holy Land at the time of the Crusades.23

Admission of the Sick Brothers to the Infirmary.

In the case of the religious knights efforts to prevent disease began before admission into the brotherhood. When a secular person had indicated his desire to join an order, he had to appear before the chapter of the brethren where he was asked, among other things, whether he was suffering from a secret disease. If he denied it and yet, after being received into full membership, it became evident he had such a disease, he could be put into irons and expelled from the order if the disease had overtaken the entire body or it was apparent that it could never be cured (T 438, cf. 445 and 672; TN Aufnahmeritual). After being admitted to full membership in the brotherhood, a religious knight who was feeling indisposed or was starting to get sick was allowed to remain for three days in his bed or in his chamber, where he was provided with his needs, including meals? In contrast, among nonmilitary orders, the Cistercians requested that their brothers who because of sickness were absent from the service seek forgiveness in the chapter and explain their absence (C, p. 201),28 St. Augustine in his Rule says: “If pain be lurking in the body, let a servant of God be believed without hesitation when he says that he is in pain,” but in case of doubt, “let a physician be consulted” (A 9). St. Augustine also states quite clearly why the sick should be given special care:

“That they may more speedily be restored to health” (A 5). This idea is reiterated by the Dominicans, with direct reference to St. Augustine: “Take heed, O prelate, not to be negligent about the sick….. so that they are restored to health more speedily, as our father St. Augustine has said” (D 1240.30).29 In the military orders the regulation about spending three days in bed before going to the infirmary was applied to ordinary brethren as well as officeholders (H 1204-1206:1193 р. 32, H ca. 1239:2213.71 and

2213.103; T 194; TN Laws 3.10).

The Teutonic Knights, while having meals in their bed, were denied meat, eggs, cheese, fish and wine (TN Laws 3.10). If, after a three-day observation period, a brother’s health did not improve, he had to go to the infirmary which was set up in every house of the order (H 1204-1206:1193.1; TN Laws 3.10). The idea of a separate room and special care for the sick undoubtedly was taken over from the rule of St Benedict which clearly states that special attention must be given the sick, who should be placed apart, in a special cell (B 36). The Templars stated quite clearly who had to go to the infirmary: “All brethren who because of their illness are unable to listen to the canonical hours and attend service in the chapel should lie in bed in the infirmary” (T 194). The Hospitallers instructed the sick to bring with them to the infirmary their bed and arms (H 1262:3030.37), though this regulation might have applied only to the permanently sick brethren. The sick Cistercians were requested to bring to the infirmary a goblet, a cup and a coverlet for their beds (C 238).

In the Dominican order the general chapter of 1296 at Paris decided that in every convent there should be established a special room for the sick, supplied with beds, linen and other needs for an infirmary; and that a principal infirmarian should be appointed to take care of the sick: their meals, beds, medicaments and everything else needed needed for their recovery. The Dominican statutes of Grand Master Humbert of Romans from 1257 present detailed regulations for the layout and equipment of a monastic infirmary. It was to be kept in good order and should have sufficient and suitable rooms with comfortable outhouses, with an adjoining garden or lawn for the recreation of the sick. The infirmary should be frequently cleaned, and all implements diligently protected and kept in good condition. Likewise, the infirmary should have necessary and proper vessels, utensils, napkins, cups, dishes and common tables, as well as single tables for eating in bed. It should also have kitchens, beds, food, medicaments, baths, heated rooms and whatever was needed for bloodletting and shaving. There should be basins for washing feet and heads, as well as for drinking and urination, and they should be emptied frequently. The infirmary was also to have stools (walkers?) for the weak to use in walking to the common rooms. There were, moreover, to be coffins, proper shrouds and everything necessary for the dead, including suitable rooms for washing the corpses. Likewise, the infirmary was to have service books for celebrating the Divine Office as well as books for the consolation and instruction of the sick, such as the lives of the Church fathers. The infirmary should be adequately provided with candles and oil lamps, and with servants according to the need, number and condition of the sick. Generally, no outsiders were to serve the sick, only brothers. However, if it became necessary to call on men from outside, then only those who were familiar with work in the infirmary and who could be trusted (D 1257.182) were to be hired. One may assume that such an elaborate infirmary was meant for the main house of the order.

In the military orders, a sick brother’s first duty was to confess to the priest and receive the Eucharist (H 1262:3039.38; T 194; TN Laws 3.10); in the case of emergency he was also ordered to receive Extreme Unction (TN Laws 3.10). The sick were to be treated with respect and patience; by such care “one certainly can gain the heavenly kingdom” (T 61; H 1204-1206:1193 p. 32; TN Rule 24; B 36). The Dominican statutes of Humbert of Romans state explicitly that a sick brother should be received in the infirmary

“with all love; he should be kindly comforted and his needs respectfully taken care of,” and then he should be assigned to his place and bed, if he were to stay in the infirmary (D 1257.182).

In the military orders the sick were entitled to special attention according to their needs and the resources of the house, in particular to receive various meats, fowl and other healthy foodstuffs (H 1204-1206:1193 pp.

32-33, cf. H 1239:2213.71, 72, 77; T 61; TN Rule 24). This regulation, no doubt, was a reflection of the Rule of St. Benedict which says: “Let the abbot take special care that the sick be not neglected by the cellarer or the atten-dants,” and “for the recovery of their strength the use of meat may be allowed” (B 36):3 The Rule of St. Basil states that the superiors are responsible for the nourishment of the sick according to their needs, and then adds:

“If something would be useful for the relief of the sick, this, too, is permit-ted, if it can be procured without difficulty, disturbance, or distraction” (BA

p. 275 and 277). The Dominicans were allowed to have meat in cases of great infirmity, according to the decision of the prelate. However, if a sick ness did not weaken him much, nor disturb his appetite during meals, he was not to be allowed to lie on featherbeds, to interrupt fasting nor to take his food outside the refectory (D 1240.30). The sick knights ate at a common table in the infirmary, where the bread and wine were the same as served the other brethren (H 1204-1206:1193 p. 33; T 298) (the quality of wine could be improved to strengthen the sick).3′ The infirm religious knights, however, unlike the healthy, were allowed to partake in two meat dishes a day (H 1204 – 1206:1193 p. 33; T 152) or when the convent brethren had two meals, the sick in the infirmary were given three; if the brethren in the convent got only one meal, the sick were entitled to at least two (T 374; TN Laws 3.8; H 1204-1206:1193 p. 33; B 36). The Dominican Constitutions make it clear that in their houses the sick should eat in the infirmary, and with the consent of the prelate might be given meat; outside the infirmary, however, eating meat was not allowed, except in cases of evident necessity or serious sickness (D 1240 and 1269.30).

Treatment of the Sick in the Infirmary.

It is very likely that medical knowledge among the crusaders and in the military religious orders in the Holy Land was mainly based on the teachings and practice at the medical school of Salerno in southern Italy. During the thirteenth century, when the statutes of military religious orders were compiled, Salerno was the most celebrated center of medical learning in the West. Emperor Frederick II in the “Constitutions of Melfi” of 1231 ordered that “no one may dare otherwise to practice or to heal, pretending the title of physician, unless he has first been approved in a convened public examination by the Masters of Salerno”; after such an examination the person obtained a license to heal from the emperor.”3 In the Holy Land, where the civilization of the Latin West met that of the Muslim East, legislation about licensing medical doctors was rather similar to that of Frederick. The Livre des assises de la cour des bourgeois (Law Book for the Burgher Court), compiled between 1229 and 1244 in Palestine, states that no foreign physician coming either from overseas (i.e., Western Europe) or Muslim countries (ce est qui veigne d’Outre-mer ou de Païnime) would be allowed to heal anybody until he had been examined by other doctors, “the best of the land,” in the presence of the local bishop. If he was found “to be a true heir of medicine,” the bishop issued him a license which entitled him to practice medicine in that city; the law book adds: “This is in accordance with the spirit of the law of Jerusalem.” However, if the physician was not found qualified to cure the sick, he had to leave the town; but if he chose to stay, he was not allowed to practice medicine again according to the law of Jerusalem.35

There is no question that the fame of Salerno physicians was well known to the religious knights, for the most renowned grand master of the Teutonic Knights, Hermann of Salza, sought a cure for his illness in Salerno in 1238.36 Our best information about the application of medical learning at Salerno is derived from the Regimen sanitatis Salernitanum (Salerno Guide of Health), an anonymous twelfth-century verse compendium, probably by several authors, on diet, hygiene, treatment of diseases and medical prac-tices. To supplement our scanty knowledge about the actual treatment of the sick by the military religious orders, a comparison is attempted in this paper between the disclosures in the statutes of the respective orders and the Regimen sanitatis Salernitanum, on the assumption that the orders’ treatment followed accepted medical practices in the West.

Regarding diet for the sick, the regulations for the Teutonic Knights are rather explicit: “Beef and salt meat, salt fish, salt cheese, lentils, unpeeled beans and other unhealthy food shall not be served at the infirmary table” (TN Laws 3.8); the Templars add cabbage, pork, goatmeat, deer and mutton (T 192). This regulation is in complete accord with the dietary rules of the Salernitan doctors: “All pears and apples, peaches, milk and cheese, salt meats, red deer, hare, beef and goat, all these are meats that breed ill blood and melancholy; if sick you be, to feed on them were folly” (p. 80).37 About cheese the Regimen adds: “For healthy men may cheese be wholesome food, but for the weak and sickly ’tis not good, cheese is a heavy meat” (p. 97). However, eggs, fish and wine, recommended for the healthy, were not forbidden to the sick. “Pork,” according to the Salernitan doctors, though nourishing (p. 82), “without wine is not so good to eat as sheep with wine” (p. 92); and “if eels and cheese you eat, they make you hoarse” (p. 95; cf. p. 125). The Regimen continues: “beans, lentils … our eye-sight molest” (p. 124); about peas the Regimen comments: “In peas good qualities and bad are tried, to take them with the skin that grows aloft, they windy be, but good without the hide” (p. 96). Furthermore, “things too salt are never com-mendable: they hurt the sight, in nature cause debility, the scab and itch on them are ever breeding, the which on meats too salt are often feeding” (p. 107). These items of advice by the Salernitan doctors are proof of the strong influence the school of Salerno had on crusader medicine.

In the military religious orders an ailing brother could refuse drinking water in the infirmary if he felt it would be harmful to him (H 1270:3396.4); the Regimen agrees:

“For water and small beer we make no question, are enemies to health and good digestion” (p. 93). Likewise, the Rule of St. Basil sees little significance in water “which nature provides for all, … but according to the advice of Paul to Timothy (1 Tim. 5:23), even this beverage should be declined if it be injurious to anyone because of physical weakness” (BA 276). It seems, however, that the curative qualities of water were very much disputed by medieval physicians.

The sick religious knights in the infirmary were excused from genuflections and from doing penance (T 345, 469, 494-496; C 203); they were also allowed to go barefoot (TN Laws 1.a), to sleep on featherbeds, mattresses and felt (TN Laws 1.p) and to cut their hair. They were not allowed, however, to shave their beards, to take medicine or undergo dangerous surgery without the consent of the master (T 195), nor to play chess (ludent ad tabulas seu ad scacos), read romances or eat forbidden food (H 1262:3039.39).

The sick brothers were entrusted to the care of medical doctors, and it was the duty of the grand commander or the master to “provide for the sick brethren a physician who shall be warned that he pay equal attention to all the brothers, who, in turn, shall faithfully follow his advice, and whoever is in charge of the infirmary shall take pains to pay equal attention to all the brethren” (TN Laws 3.11, cf. TN Rule 24; H 1300:4515.5; T 197). The Hospitallers also had special doctors for surgery (H 1268:3317.1). The Rule of St.

Augustine similarly insisted on employing physicians, and the sick monks had to submit to the instructions of the doctor (A 9). The Rule of St. Basil simply says: “When reason allows, we call in the doctor, but we do not leave off hoping in God” (BA 336) for “To place the hope of one’s health in the hands of the doctor is the act of an irrational animal” (BA 333). The Domini-cans, if their infirmarian or other brothers were not competent, were al lowed to hire outside doctors to prescribe medicine and to determine what food was needed by the sick (D 1257.182, 183). In the military orders the doctors had to visit the sick in the infirmary twice a day, in the morning an in the evening, and they were to be accompanied by the supervisor of the infirmary, also called the infirmarian (H 1262:3039.33). The doctors also had live in the house and take an oath of fealty before the brethren 00:4515.5). Medical doctors ordinarily were not members of the orders, but laymen serving the orders, 38 none of the statutes of the three military orders contain any regulations for brother doctors or brother physicians, though the duties of many other officeholders and professions within the orders are described in some detail. Likewise, there is no direct evidence regarding qualifications required of a medical doctor serving the religious knights.

The statutes, which clearly distinguish medical care for laity in the hospi-

tal from that for sick brothers in the infirmary, further state:

After the sick person has been admitted to the hospital, he shall, at the discretion of the hospitaller, who shall decide what he needs for his illness, be cared for diligently, with such discretion that in the main house, where is the head of the order, there shall be physicians according to the means of the house and the number of the sick (TN Rule 6)

whereas in curing the sick brothers who “are entitled to special care and attention” a physician’s advice shall be followed, “if a physician can be conveniently secured” (TN Rule 24). However, it cannot be denied that occasionally a physician might become a member of the order, for the Admission Ritual of the Teutonic Knights states: “If any brother knows a trade they shall inform the master [at the time of admission to the order] and practice it according to his wish and their skill.”39 But such brother physicians then would come under the jurisdiction of the grand commander as

“lay brothers and their domestics, who live in the house” (TN Customs 28). 40

The Templars, who did not run a hospital, in a single paragraph in their statutes make reference to medical doctors who shall be provided for the sick brothers either by the provincial commander or the master (T 197). The Hospitaller statutes of William of Villaret state explicitly: “It is decreed that no secular person, who is in the service of the house, should have footwear of the brothers, except … doctors of medicine or of surgery” (Statutum est quod nullus secularis homo, in servitio domus existens, fratrum habeat calceamenta, exceptis… medicisque fisisce et cirurgie… H 1300: 4515.18). The Infirmarian

(infirmarius), however, was a brother knight in charge of the infirmary (TN Rule 24) and was appointed either by the commander of the house or the grand commander. The Dominican Constitutions give a detailed description of the qualities and duties of an infirmarian he is in charge of the general care of the sick and the infirmary; to this office should be appointed a brother who is known to be patient with the sufferings of the sick and compassionate with their sickness and necessities; who is soft in his speech and fluent in using consoling words; foresighted and discreet in caring, serving, and administering all that is necessary, including medicine, for the sick in the infirmary as well as to those in the convent, and yet is not prodigal in using anything without reason. He must visit the sick frequently and discuss with the cook and other officeholders what is needed for them.* The expenses for these provisions were paid by the procurator; however, accounts for such expenditures were submitted to the chapter; the chapter was also informed of any special substantial gifts collected for the sick (D 1257.181, 182). Any negligence had to be corrected as soon as possible and any worsening of a brother’s health had to be reported to the prelate and the chapter so that prayers might be said for them. If in the chapter something was discussed that concerned the sick brothers, they were to be notified of it (D 1257.181, 182). Similar attributes and responsibilities also were required of the deputy infirmarian (servitor infirmorum). Among his other duties, he had to call the sick, by ringing the infirmary’s bell, to meals and to wash their hands. Infirmary servants (servitores speciales), under the direction of the deputy infirmarian, had to assist those confined to bed. Likewise, they had to sleep in the infirmary to help the sick day and night. The infirmary servants also had to assist the physicians to preserve urine for examination, to prepare meals for the sick, to serve at the table, and to wash the clothing and blankets of the sick (D 1257.182- 183).42 The Rule of St. Benedict states that it is the infirma-rian’s duty to supply provisions for the infirmary, including food (B 36). The Rule of St. Augustine says simply that the care of the sick should be entrusted to someone whose duty it was to get from the cellarer what each patient needed (A 9). Among the Cistercians, the infirmarian had to celebrate the divine office for the sick, light the candle at matins, provide the sick with service books from the library, and other necessary things from the cellarer and the kitchener. On Saturdays, for those sick who wanted it, he had to wash their feet and put their clothing in order. It was also the infirmarian’s duty to dispose of the blood of those who were bled, clean the bloody vessels and in winter make fire in the stove. Moreover, he had to handle the special tasks associated with death: prepare for the funeral, wash the dead body, and provide a coffin and gravesite (C.238-239).43 However, the Cistercians make no specific mention about curing the sick, nor about physicians.

In the Order of the Temple, the infirmarian had to secure all provisions including food; he even was in charge of the wine cellar, main kitcher bakery, pigsty, fowlsheds and garden; if the commander of the house did not wish to entrust the infirmarian with these offices, he had to give the infirma-rian sufficient money to buy all necessities for the infirmary (T 196). The provincial commander was responsible for supplying the infirmary with medicine (T 196). The Rule of St. Basil, after stating that the human body is susceptible to various hurts from within and without by the food we eat and both excess and deficiency,” fully recognizes the need of medicine for curing the sick: “We would not require the medical art for relief if we were immune to disease,” therefore “the medical art was given to us to relieve the sick, in some degree at least” (BA 331).* In the Order of the Hospitallers, the infirmarian was requested to render a monthly account, to the grand commander, of the things he had used and those still on hand (H 1301:4549.15), and a yearly account, to the general chapter, of the quantity of coverlets, sheets, blankets and mattresses in the infirmary (H 1304:4672.11).

No direct information about the drugs and medical treatment given in the infirmaries of the orders has survived, but it seems likely that, besides improved food and bloodletting, spicy herbs, syrups and electuaries were the basic therapeutic agents. Reference to medieval medical authorities shows these were the commonly used treatments. About the usefulness of various herbs St. Basil says: “The obtaining of that natural virtue which is in the roots and flowers, leaves, fruits, and juices, or in such metals or products of the sea as are found especially suitable for bodily health, is to be viewed in the same way as the procuring of food and drink” (BA 331); he recommends “to employ this medical art” as a parallel to the care given to the soul (BA 332). The use of syrups (sticky liquids of fruit and vegetable juices cooked with sugar) and electuaries (pasty masses of honey or sugar and drugs) and spices was forbidden to the brethren of the Teutonic Knights without permission (TN Laws 3.7). These remedies were reserved, as was common in the Middle Ages, for the sick. However, sugar for making syrups certainly was used by the Teutonic Knights, for already in February 1198 (thus before the German hospital in Acre was transformed into an order) the hospital received sugar for the needs of the sick a The infir-marian in the Order of the Temple was requested to buy syrup in town if a brother in the infirmary requested it (T 195).

The Salerno Regimen also offers a wide range of spices or aromatic herbs and plants that were used either for the preparation of various robs (cooked fruit or vegetable juice without sugar) and syrups, or with wine. Anise and fennel seeds comfort the stomach and clear the eyesight; fennel was recommended also for ague and for breaking wind (p. 105). Caper was used for the spleen (p. 106), and elecampane drunk with rue in wine was wholesome for the stomach (p. 119). Wine, mixed with spices, was regarded as good medicine for all ills and its use was recommended in the Regimen, particularly during the winter (p. 130). St. Paul recommended a little wine in lieu of water “for thy stomach’s sake and thy frequent infirmities” (1 Tim. 5:23),16 The Teutonic Knights, like the religious in general, were forbidden to make or consume spiced wine (German lutertrank, Latin pigmentum) (TN Laws 1.o)

To vinegar, a natural by-product of wine, the Salernitan Regimen ascribed several healing qualities: cooling, drying, and clearing the complex-ion. It increased appetite and reduced fattening, and was also used as a sexual sedative and especially as a disinfectant (p. 103). Ground black pepper was recommended for breaking wind and for a cold in the stomach, but white pepper for coughs and ague (p. 122). When these spices, syrups, and electuaries are compared with corresponding medicine used by Muslim physicians in the late twelfth and early thirteenth centuries, as described in The Medical Formulary of al-Samargandi, one notices a close similarity in the prescriptions of Salerno and Arab physicians.*7 Likewise vinegar was a common remedy among both groups of physicians. This similarity also extended to other medical practices.

In the orders, one way of improving the health of a sick brother was bathing: only the sick in the infirmary were allowed to bathe; 48 all others had to obtain the permission of their superior (H ca. 1239:2213.102; TN Laws

3.11). The Rule of St. Benedict states:

“Let the sick be allowed to bathe as often as expedient, but those in health, and especially the young, shall seldom be permitted to do so” (B 36). The same idea is reflected in the Rule of St. Augustine: “A bath should be by no means refused to a body when compelled thereto by the needs of ill health. Let it be taken without grumbling when ordered by a physician,” but a bath just for “pleasure” should be denied (A 9). 4 According to the Order of the Hospital “a brother should not go to [thel baths, except of necessity, with the knowledge of his bailiff, and if they be three or four together”.

The Salernitan Regimen recommends bathing in the spring, advises keeping warm after a bath, and adds: “Wine, women, bath, by art or nature warm, used or abused do much good or harm” (p. 84; cf. p. 124). Similarly, al-Samarqandi’s Formulary contains a brief chapter on aromatic bathing, recommending it as a therapeutic exercise.

The statutes of the three military orders also contain long and detailed regulations about fasting. so Although the idea of fasting in religious orders was based primarily on biblical instructions and monastic rules, 5′ it was undoubtedly also regarded as a form of dieting, to keep the human body in good health. 52 The Regimen is also very explicit about the benefits of diet and fasting: “To keep good diet, you should never feed until you find your stomach clean and void” (p. 80). Fasting was recommended in every season: thus, “To fast in Summer does the body dry,” it was also regarded as a remedy for vomiting (p. 128). The religious grounds for fasting were completely ignored by Salerno doctors

Special treatment was required for those brethren who had contracted a contagious digestive illness. Brethren “who are wounded or have dysentery or other sickness, which may disturb the comfort of the others, shall sleep apart until they recover” (TN Laws 3.13). The Templar statutes add:

“brethren suffering from purulent wounds, vomiting or raving madness, should be kept in a separate room close to the infirmary” (T 194).** Likewise, brethren suffering from quartan fever were given meat, with the master’s permission, three days a week during the fast period before Advent and Christmas; they were also exempt from attending divine worship (TN Laws 3.14). If an ailing brother could not eat the ordinary infirmary fare, he was allowed special food until he recovered enough to partake in the common infirmary meals (TN 190). These regulations may be compared with those of Salerno and Arab physicians. To those who suffered from dysentery (the flux) the Regimen advised fasting (p. 98); about malaria, called ague, the Salerno physicians said that it is bred by long sleep after noon, and recommended as a cure butter (but not milk) (p. 97), white pepper, purging and bloodletting (pp. 97, 122, 130). For fever, al-Samarqandi recommended cress powder and lohochs, syrups, and lozenges, “but the keynote in treating fevers is the opening of blockages which cause putrefaction of humor” (p. 93).

Bloodletting (venesection or phlebotomy) was regarded as a universal remedy and preventive for all maladies during the Middle Ages. The Salerni-tan Regimen states that, for treatment of the several overflowing humors, diet, drink, hot baths, purging, vomiting and bloodletting are all recom-mended, but “the last of these is best, if skill and reason,” the age and strength of the patient, the quantity of blood let and the season are all respected (p. 147).

According to the Regimen, venesection should be performed early in the morning (p. 153) and it suggests that the best times are April, May and September, because during those months the moon exercises the greatest sway upon the benefits of bloodletting. However, venesection should be avoided on the first day in May and the last in April and September (p. 149).

The Teutonic Knights also regarded different days as baleful for venesection -thirty-two in a year. On these days every man shall be on guard to keep himself away from venesection or to begin anything at all, for such endeavors will come to a bad end. Above all, however, every man shall make sure that no blood is let on these two days: on the first day in December and the eighth day in April. If one is bled on these two days he will die, beyond doubt, within forty days. Whoever is bled on the fourth, fifth and sixth day in March, or on the eleventh day in April, or towards the end of March. will not be able to endure the cold of the winter.5s

Cistercians and the Dominican friars were bled four times a year: in February, April, June and in September or December, and, according to the dietary period, between terce and sext or sext and nones, with the consent of the prior or a doctor.

According to the Salernitan Regimen, the presumed effects of bloodletting were many; it renewed a person’s spirit and senses as well as improving his appetite, sleep and sensation (p. 148); even the spleen, breast and entrails were helped (p. 150). The Muslim Syrian traveller Usamah, after telling his listeners that bloodletting was widely practiced by Muslim physicians to cure sickness, recommended phlebotomy even after heavy bleeding from wounds.56

The regulations of the military orders are rather terse on venesection: the Hospitallers, like the Templars and the Teutonic Knights, needed a superior’s permission for bloodletting (H 1204-1206:1193.9 p. 37 and H ca. 1239:2213.105; T 195; TN Laws 3.12) and a Hospitaller who had “himself bled without leave unless it be because of illness” had to undergo the septaine (a seven-day penance) (H ca. 1239:2213.78). The ordinary day for venesection among the Hospitallers was Saturday (H 1206:1193.9 and H ca 1239:2213.105). After venesection the Hospitallers were allowed to have three meals with a pittance (H 1206:1193.9 and H ca. 1239:2213.105); Templars could have their meals in the infirmary, although they could also demand instead the ordinary convent food (T 191); the master after venesection was allowed to take his meals in his chamber (T 86).

Surgery, Divine Worship and Care for the Old.

Surgery, if one believes ‘Usamah, was more advanced among the Muslims than among their Western contemporaries. Nevertheless, it was favored neither by the Muslim nor the Christian faith because of the prohibition in the Koran and the Bible against spilling human blood and because of the sanctity of the human body, which was created by God in the likeness of God. The Old Testament says: “Whosoever shall shed man’s blood, his blood shall be shed: for man was made to the image of God” (Gen.9:6; cf. Gen.1:27; Gen.4:11;

Num.35:18; Num.35:33; Deut.19:12; Matt.26:52). Moreover, Innocent III in the Fourth Lateran had forbidden subdeacons, deacons and priests to participate in surgery if cutting and burning were performed. & The statutes of the three military orders are silent about the practice of surgery. The Rule of St.

Basil, however, clearly accepts the usefulness of surgery, though not mentioning monks in particular: “Right reason dictates, therefore, that we demur neither at cutting nor at burning,” and again, “in using the medical art we submit to cutting, burning, and the taking of bitter medicines” (BA 332 and 334).

Besides diet, treatment by medical doctors and bloodletting, another form of comfort for the sick in the infirmary was divine worship. The Rule of the Hospitallers states that “the priest should go in white raiment to visit the sick, bearing reverently the Body of Our Lord, and the deacon or the sub-deacon, or at least an acolyte, should go before, bearing the lantern with a candle burning, and the sponge with the holy water” (H 1125-1153:70.3; cf.

H ca. 1239:2213.65).61 Among the Teutonic Knights divine service was rather similar: “Care also shall be taken that every Sunday a priest and a student assistant say the office of the day or of Our Lady, read one Epistle and the Gospel, as is most convenient, where most of the brethren are lying” sick (TN Laws 3.12). The Cistercians emphasized the importance of regular attendance at divine worship for those in the infirmary; if the sick could not participate in the services in the chapel, the Hours were to be celebrated in the infirmary (C 202- 203). St. Basil advised his monks that if their medicine failed, they should “rest assured that He will not allow us to be tried above that which we are able to bear” (BA 332). In particular, Basil addresses those

“who have contracted illness by living improperly”: they should heal their bodies “for the cure of their soul” (BA 336).62

A particular problem for the crusading knights was caring for the brethren who were old, disabled or incurably sick. The statutes of the Teutonic Knights stated explicitly: “The old brethren and the infirm shall be generously cared for according to their infirmity; they shall be treated with patience and diligently honored; one should not in any way be rigorous as to the physical requirements for those who bear themselves honourably and piously” (TN Rule 25; T 60, 339, 837). If they were not able to genuflect and stand up with the others divine worship in the chapel, they were to stand behind the others (TN Laws 3:15, T 147); they were even allowed to sit during the service (T 359). In short, the master, shall see to it that the brethren who are so old or so young or so feeble that they need it, shall receive better care than the others” (TN Laws 3.15). The old and the feeble brethren also were given better meals than the healthy (H 1125-1153:70.8;

T 191, cf. 323). It seems that the Hospitallers quartered their incurably ill brethren in the order’s hospital (H 1304:4672.4); the Teutonic Knights also sent their old and sick brethren from the Holy Land to European comman-deries to spend their old age in houses where “the sick are customarily cared for” according to the requirements of their sickness (TN Customs 13).

The Rule of St. Benedict asked the brothers to display kind consideration to the old, their weaknesses should always be taken into account and the full rigor of the Rule should not be enforced regarding food (B 37). St. Augustine ruled that those in a weak condition “should be entrusted to some one person” (A 9); and St. Basil said that in cases of chronic illness “we should amend the sins of the soul by assiduous prayer, prolonged penance and severe disciplinary treatment” for very often “the diseases which we contracted were for our correction” (BA 233 and 234). In Cistercian houses, brothers who were too feeble to handle ordinary conventual life, but who did not want to go to the infirmary, might, with the abbot’s consent, sit in the chapel and sing and read, and perform such duties as their feebleness permitted; the same applied to the feeble in the infirmary (C 202-203).

Cistercian regulations are rather vague about medical treatment of the sick in the infirmary; it seems that the main concern was maintaining quiet and order rather than providing medical treatment. Those who disobeyed in-structions, disturbed others or complained about their treatment were re-proached; if, after repeated admonishing, even before the chapter, they did not reform, they were, their feebleness permitting, subject to regular disci-pline. Maintaining silence was another important aspect of the life in the infirmary: speaking was allowed only when absolutely necessary, and then in subdued voice and in designated places.

Another problem for the religious knights was caring for brethren who became sick while doing penance. Ordinarily a punished brother doing a one-year penance had to sleep in the infirmary, and if he became sick, he was cared for like the others and given the meals of the infirmary (T 470, 494, 495, 643, 654; TN Laws 3.45). While ill, he was exempted from receiving the discipline in the chapter but was flogged by the chaplain instead (T 505).

However, as soon as he was well again, he had to resume his penance, sit on the floor among the members of the household, eat his meals and work with the slaves (T 470; TN Laws 3.45).

In Part II of this series, however, we will dive deeper into the Order of the Hospital of St. John of Jerusalem or the Knights Hospitallers.

Source: BULLETIN OF THE HISTORY OF MEDICINE Vol. 57 Pp. 43-69 (27 Pages)

Leave a comment