Introduction

Stewart starts by describing the origins of the concept of a state medical service. As early as 1907 the Fabian Society was advocating a nationalized medical service and Beatrice Webb had presented a memorandum on a unified medical service, with an emphasis on prevention, to the Royal Commission on Poor Law.

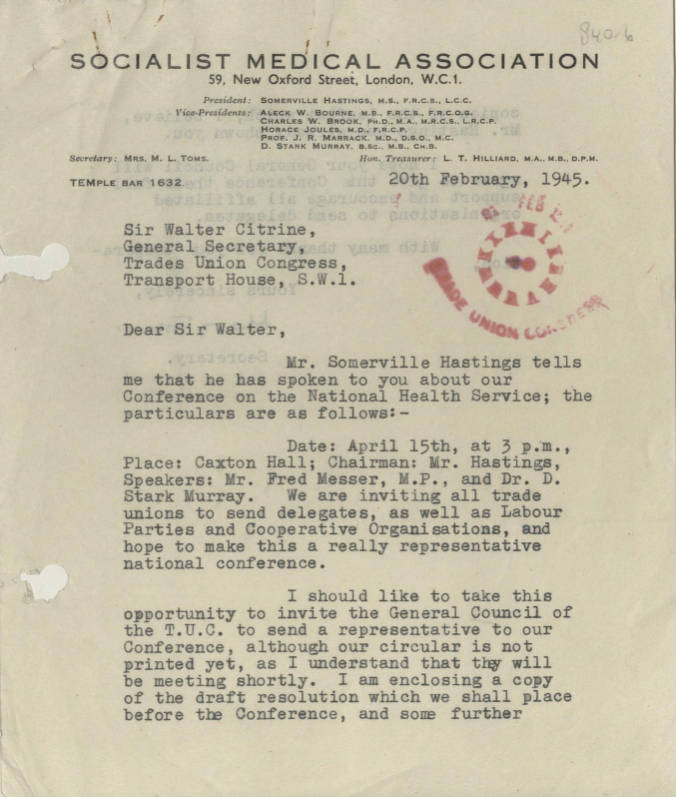

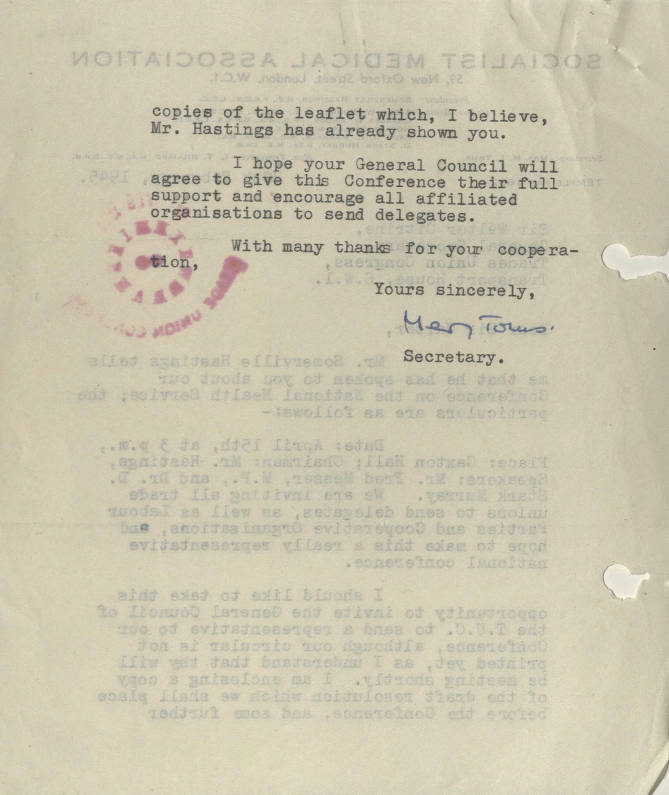

The SMA (Socialist Medical Association) was founded in 1930 by a small group of socialist doctors under the leadership of Dr Somerville Hastings, its first president, and Dr David Stark Murray, the tireless vice-president. The Association subsequently provided much of the basic thinking behind the NHS, which was inaugurated in 1948.

Hastings was a distinguished consultant ear, nose and throat surgeon on the staff of the Middlesex Hospital. By 1930 he also had considerable political experience as an MP and as a councillor on the London County Council. There were very few socialist doctors in England at that time and little attention was paid to them as a whole, but Hastings, because of his professional status and political experience, he could not be ignored. As a councillor in the Labour LCC he was also playing a big part in upgrading the old Poor Law infirmaries in London into modern hospitals under the 1929 Local Government Act.

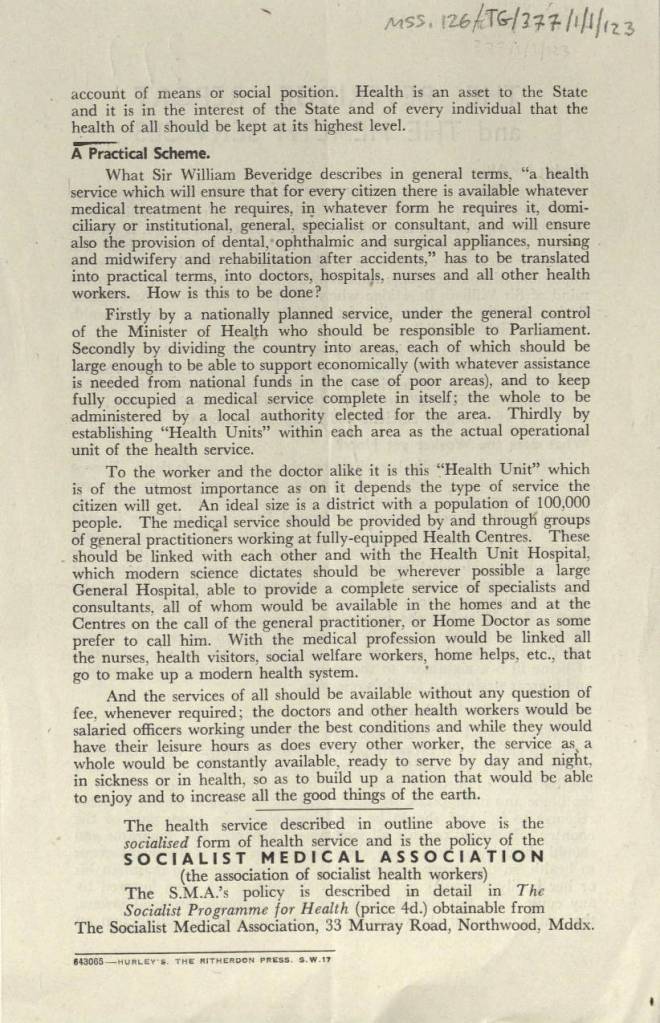

The initial aim of the SMA were “to work for a socialised medical service, both preventive and curative, free and open to all; to secure the highest possible standard of health for the British people and to propagandise for socialism within the medical and allied services.” Later, the SMA also came to advocate unification of the hospital service, that all doctor should be salaried and that the service should be democratically controlled and administered by the local authorities.

The Genesis of the SMA

1900-1930

The physical condition of the working class had long been a labour movement concern. As the leading SMA member David Stark Murray put it, rather melodramatically, during the passage of the National Health Service Bill in 1946, when it came to such a health service ‘Keir Hardie thought of it in 1868 when he first went down a pit. Early socialist analyses tended to see in the abolition of capitalism the solution to all problems, including those related to health.

This attitude persisted well into the twentieth century, and one of the principal arguments of the SMA was to be that capitalism per se and the capitalistic organisation of medical care both contributed to individual and national ill healthcare.

One of the central problems of social democracy is highlighted by such analysis; that is, which is to be prioritised; economic reform which ultimately will be to the material benefit of the whole population, including the working class: or social reform to ameliorate, in the relatively short term, the conditions under which working class people are currently disadvantaged?

As Webster points out, the Labour Party was, from its foundation in 1900, committed to the abolition of the Poor Law, which in itself implied the creation of medical services free from the stigma of pauperism.

The early 1900s also saw the formation of several left-wing medical pressure groups, and Murray further claimed in 1946 that the original pioneers of state medicine were to be found in the Edwardian period. He gave particular credit to the SMSA, discussed further below, and to the individuals such as Dr George Geddis of the independent Labour Party (ILP), who had attacked private practice and proposed in its place a state salaried system. As Murray put it, Geddis ‘visualised the profession as a disciplined army waging war against the forces that threaten the national health,’ a telling metaphor given the SMA’s identification of the ‘battle for health.’

Competition within the medical profession, as currently existed, was harmful in that it reduced fees, destroyed ‘fraternal cooperation,’ and hindered scientific progress. Hospital services too were inadequate, and overall, a ‘co-ordinated state medical service’ was required. Interestingly, for as we shall see this was to be an SMA concern, Dodd emphasised the benefits of such a scheme for the middle class, and his speech was one of a series on ‘Socialism and the Middle Classes’.

The Webbs and the Medical Services

But the first really important left-wing articulation of the need for the reform of healthcare provision came from that quintessentially Fabian partnership, Sidney and Beatrice Webb, initially through the Minority Report of the Royal Commission on the Poor Law.

Beatrice presented her memorandum on the medical services of the Poor laws and Local Government Public Health Departments to the Royal Commission in September 1907. This was, typically, both highly detailed and historically informed. The dual nature of the existing system – that is the division of responsibilities between the Poor Law and local government – resulted in two different parts working to different principles and aims, the outcome being ‘chaos, almost ludicrous in its paradoxes’. This notion of anarchy in the health services – manifested by overlaps, omissions, and lack of any coordination or planning – was to be central to left- wing critiques over the next thirty years. Webb’s solution, conforming to her more general; aim of breaking up the Poor Law, was a unified preventive service, although at this stage she saw no need for an end to private practice or voluntary hospitals.

The Webb memorandum was published in 1910 as The State and the Doctor. Here the point was made that despite untold millions being expended on health, the end result was two separate and ill-coordinated services, one consequence of which was a huge, undiscovered, volume of disease, particularly among the young.

From the ‘standpoint of national health’ medical relief might be seen as ‘worse than useless’. It encouraged individual patients to have ‘faith in taking of medicine instead of reliance on hygienic regimen’, and thereby counteracted the ‘efforts of the Public Health medical service in the promotion of personal hygiene’.

They pointed out, for example, that those who had ‘neglected the elementary duties of personal cleanliness’ by becoming infested with lice could receive free treatment and, in some cases, replacement clothes, all without the stigma of pauperism. By contrast, the individual who contracted an occupational disease ‘in the earning of his daily bread’ had no rights to medical treatment unless he or she became destitute. Apart from any other reason, therefore, health reform was needed to ‘curb physical self-indulgence … and positively heighten the desire and capacity of all persons to maintain themselves’.

As we shall see, SMA members were to argue that, when a fully socialised health service was in place, individuals would have significant responsibility for the maintenance of their own bodies. Duties as well as rights were to be emphasised in the Association’s vision of healthcare in a socialist society.

For all others, the ‘prosperous workman, or the stingy person of the lower middle class’, there would be no incentive to use public services, since they would be charged as in private medical practice.

Hence those who could afford it would exercise their right to ‘free choice’ of doctor should be confined to the private sector. This did not mean, though, that was no place for state salaried practitioners. Each public health department was to have available ‘the necessary staff of whole-time salaried officers, including clinicians as well as sanitarians, institution superintendents as well as domiciliary practitioners.

Sidney and Beatrice Webb proposed significant far-reaching changes in healthcare provision while suggesting that some existing features remain in place. Subsequent reformers, including the SMA, were to be deeply influenced by their ideas. In particular, the importance of preventive medicine, a unified service, the local authority control was to be central to the Association’s plans for a socialised health service. Other aspects of the Webbs’ thinking, however, were to be rejected, especially the continuance of voluntary hospitals and of private practice.

The contemporary response to the Webbs of one individual, Somerville Hastings, is particularly noteworthy in the context of this study. Hastings, the most important figure in the SMA’s early history, was later to recall the role of both his medical training and his religious background in shaping his political beliefs.

Somerville Hastings in the 1920s

Another such group was, of course, health care professionals/Involvement of healthcare professional in the SMA activities.

The SMA was founded by doctors in the Labour Party, and it is therefore appropriate to examine what some of these were saying in the decade prior to 1930. Murray, for example, wrote a series of articles for The Scottish Co-Operator dealing not only with health and the medical services, but also with some of the reasons for their importance to modern society. It was, he argued, possible to assess a nation’s level of political development by the measures it employed for health promotion, and on such criteria, Britian was, along with the rest of the world, ‘extremely backward’.

In a talk to new students at the Middlesex Hospital in 1923 entitled ‘Team Work in Nature’, he suggested that Darwin had shown that the natural world was characterised not only by competition, but also by cooperation. The latter was also to be found in medicine, where staff of all types ‘are united in the single purpose of healing the sick’.

For Hastings, ill health was part of a wider structural problem of capitalism.

Poverty was ‘body- and soul-destroying’ as was attested by data on, for example, infant mortality and the rejection of potential army recruits as a result of poor physique. Socialism alone was the answer.

Rather, the GP should be part of the health team, hence the significance of health centres, associated and integrated with local hospitals. While Hastings was prepared to concede that the voluntary hospital system had some significant achievements nonetheless public health was suffering because hospitals worked as isolated units, and had little real contact with general practitioners.

Overall, therefore, what was required was a comprehensive, national scheme with, in each locality, the hospital at its centre and with the aim of providing ‘the best possible service free to everyone who wished it’. Prophetically, Hastings was suggesting in the mid-1920s that a nationalised hospital system was inevitable within 10 to 20 years.

Back to the story…

In the local village chapel, for example, he found ‘the cradle of democracy’, and Hastings was to remain committed to the view that true democracy and socialism were mutually reinforcing.

Hastings was deeply impressed by the Minority Report and publicly to it, arguing that that the Poor Law had to finally be broken up. As the Webbs suggested unification would make things cheaper and administratively simpler.

The State Medical Service Association

The Webbs provided an important scheme for socialist medical reformers, one which would continue to be influential into the 1940s. However, theirs was not the only model. In 1911 Bejamin Moore, Professor of Biochemistry at Liverpool University, who in the following year was going to be instrumental in founding the State Medical Service Association, published his proposals for medical reform. Moore suggested that a ‘National Health Service’ would both strengthen the ‘physique of the race’ and save national resources.

Realistically, however, the creation of such a system would take a whole generation, partly because of the anticipated hostility of the medical profession.

The SMSA held its inaugural meeting in July 1912, and by the end of the year had organised itself into various committees. Among these was the propaganda committee, which Somerville Hastings joined in late 1912 and of which he was, by the early next year, secretary.

The organisation was primarily concerned with a salaried service and a unified hospital system. Its eight founding principles are as follows. First, a state medical service to be administered by a Board of Health under the supervision of a Cabinet-rank minister, the Minister of Public Health.

The need of a separate health ministry was prominent among the reformers’ demands in the Edwardian era.

Second, one of the service’s ‘primary objects’ should be the unification of preventive and curative medicine.

Third, entry to the medical profession should be by one state examination only.

However, the other five founding principles of the SMSA began to move off in a potentially different direction. First, the whole profession was to be organised along the lines of existing state services.

Second, medical salaries should be increased gradually according to the length of service and position, and should attract pension rights.

Third, and again in theory compatible with previous reformers’ aims, the public ought to have a choice of doctor, while no practitioner should be required to take on more than a certain number of patients.

Fourth, and here there is a much more obvious break, with, for example, the minority report, all hospitals should be nationalised, and used for the various types of medical care and treatment in conjunction with the patient’s own doctor.

Finally, the services of all state doctors should be available to everyone, irrespective of income. This is in obvious contrast to the Webbs’ idea of encouraging those who could consult private practitioners.

The People’s Health

It is a basis for the principles of argument put forth by the association aimed for a socialised medical service.

The founding of the Socialist Medical Association

First, the question of a state medical service had again been under discussion by left-wing medical activists, both in the National Medical Service (successor to the SMSA) and, more specifically, as a result of an article by Hastings on the future of medical practice which appeared in the Lancet in 1928. Second, Brook, following a speech to an LCC meeting, had been contacted and visited by the Berlin dentist Ewald Fabian. Fabian was involved with the German socialist doctors’ organisation whose journal, Der Sozialistische Arzt, he also edited, and was keen that British socialist doctors set up a similar body.

The SMA later repaid its debt to Fabian by sending funds in the summer of 1933 to help his journal out of its financial difficulties and by securing his release from a French internment camp at the beginning of the Second World War. Third, Brook was particularly incensed by a speech hostile to state medicine made by the Independent MP for London University, Sir Ernest Graham-Little MD. This prompted him to write to the labour newspaper The Daily Herald proposing the setting up of an organisation of left-wing medical practitioners.

Webster adds a further possible factor by suggesting that the creation of the SMA might have been in response to the BMA’s A General Medical Service for the Nation, first published in April 1930. There is no direct evidence of this in statements by Association founders. But certainly, it would have been part of the general context described earlier, since at least one reason behind the BMA document was, as Peter Bartrip, puts it, the desire to halt ‘local authority “encroachments” on private practice … and to pre-empt government plans for a service antipathetic to BMA priorities.

Contact was also made with foreign socialist medical organisations. As Weber suggests, the founding of the Association ‘reversed the decline’ in Labour Party discussion of health issues which had taken place in the mid- to late 1920s, creating a ‘new forum for mobilising the expertise of socialist doctors. How effective this was remains, however, rather more problematical.

Later in 1931 Brook and Hastings appeared before the Party’s Organisation Sub-Committee, and the Association was duly affiliated. This political commitment distinguished it from earlier bodies such as the SMSA, and opened up the possibility that the SMA might have a real chance of seeing its programme and put into action.

The organisation’s first delegate – Hastings – attended a party conference in 1932.

Second, Hastings gave a key-note speech, ‘The Medical Service of the Future’. This is worth analysing in some detail for the clues it affords as to what the SMA sought. Seven basic principles were identified:

1. A preventive service;

2. The end of economic barriers to medical care;

3. The importance of hospitals;

4. The centrality of teamwork;

5. The revised role of the general practitioner;

6. Free choice of doctor; and

7. Professional freedom.

The principles of socialised health care

The two key formulations of Association policy in the 1930s were The People’s Health and A Socialised Medical Service. Particular attention will be paid to these, and to how their arguments were built upon in further statements by the SMA and its leading members.

The international character of medicine

The SMA weas firmly committed to internationalism: medical knowledge was shared across national boundaries, and socialism was, by definition, internationalist.

The Association had an ongoing interest in the health service provision of other nations – hence the regular MTT column, ‘Medical News of the World’. In the 1930s Hastings in particular also visited various foreign countries. In 1931, or example, he and Salter travelled to the Soviet Union. Hastings subsequently praised the country’s prophy-lactoria or health centres, commending especially their apparent efficiency, medical division of labour, and preventive as well as curative functions.

Despite the scepticism of some Association members about the Bolshevik regime, Soviet healthcare was often held up by the left as an example of what could be achieved in a socialised system.

This process was almost certainly furthered by the publication in 1937 of Henry Sigerist’s book on medicine in the USSR, the subject of a favourable review in MTT.

But the USSR was not the only country from which the Association could derive inspiration. Certain characteristics of social democratic Sweden’s health provision were also much admired. Hastings visited Sweden in the early 1930s and reported that in terms of organisation and equipment its hospitals were ‘the best in the world’. He was inspired enough by what he had seen to claim that at least in the sphere of health Sweden was ‘solving to some extent the difficult problem of the transition from Capitalism to Socialism’. It seems likely that Hastings was particularly won over by the fact that the Swedish hospitals were run by local authorities… with the Soviet Union, he was also taken by the availability of a scholarship scheme for medical school.

The SMA and the London County Council

It has already been noted that the SMA’s membership in the 1930s was heavily concentrated in the London region. A more general and a locally authoritarian model of socialist organisation was in place in the wake of the Labour’s election victory in 1934.

This included the administration of welfare services that formed an important strand in Labour ideology.

‘For a healthy London’

An SMA London and Home Counties branch was formed in mid-December 1930 with Dr Morgan Finucane as chairman and Dr Powell-Evans as secretary, and subsequently affiliated to the LLP in 1937.

A first draft, whose principal authors were Salter, Brook, and Hastings, was presented to the LLP Executive in January 1931. Ultimately this document was published as the election leaflet: For a Healthy London: A Municipal Hospitals Policy that will Lessen Suffering and Disease. This noted the current problems in voluntary and municipal hospitals. A Labour administration would finally break the link between hospitals and the Poor Law by fully exploiting the 1929 Act’s potential. Patients would be admitted because they were London citizens – for whom only ‘the best is good enough’ – needing treatment. The aim was not only to make London’s municipal hospitals the best in the world, ‘but ultimately to make them free to all, rich and poor alike’.

Its 1934 report, The Public Health of London, constituted a health manifesto for the impending elections. While noting the advances in public health, and their impact on the general death rate, the document also pointed out to worrying trends in the capital, including rising maternal mortality and deaths from diseases such as cancer. Ill-health was the product of three factors – poverty; bad sanitation; and inadequate medical care and treatment.

Fascism, Medicine and War

First, socialism was, by definition, internationalist.

Second, if socialism was international, so too was medicine. Doctors traditionally had access to all medical knowledge, whatever its country of origin. MTT argued, during the diplomatic crisis of spring 1938, that medicine was ‘international in the highest sense of the word’.

Fascism involved the abnegation of ‘the universal spirit that has developed in the medical profession during the past centuries.’ Every doctor aware of medicine’s debt to ‘men of every race, of every religion, and of every shade of opinion’ should condemn fascism and work for the spread of ‘a true international spirit’. Furthermore, medicine’s internationalism could, Murray argued at the height of the Second world war, make it the basis and inspiration of a global system prioritising citizenship over nationality. Third, medical organisation could benefit from other countries’ experiences.

Fourth, in war it was the medical profession that had to repair human damage, and so knew best its human costs. Doctors therefore had a particular duty to agitate for cooperative solutions to international problems. In this, they would be aided by their greater influence over the community than any other profession’.

‘Health of the Future’

The wartime era saw Association members involved in a wide range of activities, in addition to their own demanding work. These activities included the publication of a significant volume of literature, an already existing characteristic of the organisation in itself a reflection of the literate, educated nature of its membership. Among these texts were contributions by Murray and by Aleck Bourne to the famous ‘Penguin Specials’. In this series, which during this period focused especially on proposals for post-war reconstruction, was later seen as an important contributory factor in the Labour’s 1945 election victory.

Whither Medicine? – Reviewed existing potentials for public health reform. ‘Highlands and Islands Scheme’ discussed certain foreign healthcare systems with that of the USSR.

‘The Beveridge Report and its Impacts’

The SMA pressed on with its support for the Beveridge-the need for a socialised health service, based on the now familiar components of teamwork; preventive medicine; and democratic control – a new health service should not be ‘imposed from without or above’; was restated, as was hostility to any extension of the panel system.

1963), arriving at the House of Commons to deliver his report on social security and state welfare on 18 February 1943.

‘The Battle for Health’

National Service for Health

The pamphlet was broken into three ‘chapters’: the first asked what medical services were needed, and why; the second described the current system; and the third showed how the criteria adopted in the first could only be met by a state medical service. The underlying aim of any scheme, it was argued, must be the maximum mental and physical fitness of every citizen. Full health was an individual’s greatest asset, and a nation’s greatest asset was a healthy population.

Source; The Battle for Health-John Stewart

The NHS-Susan Cohen

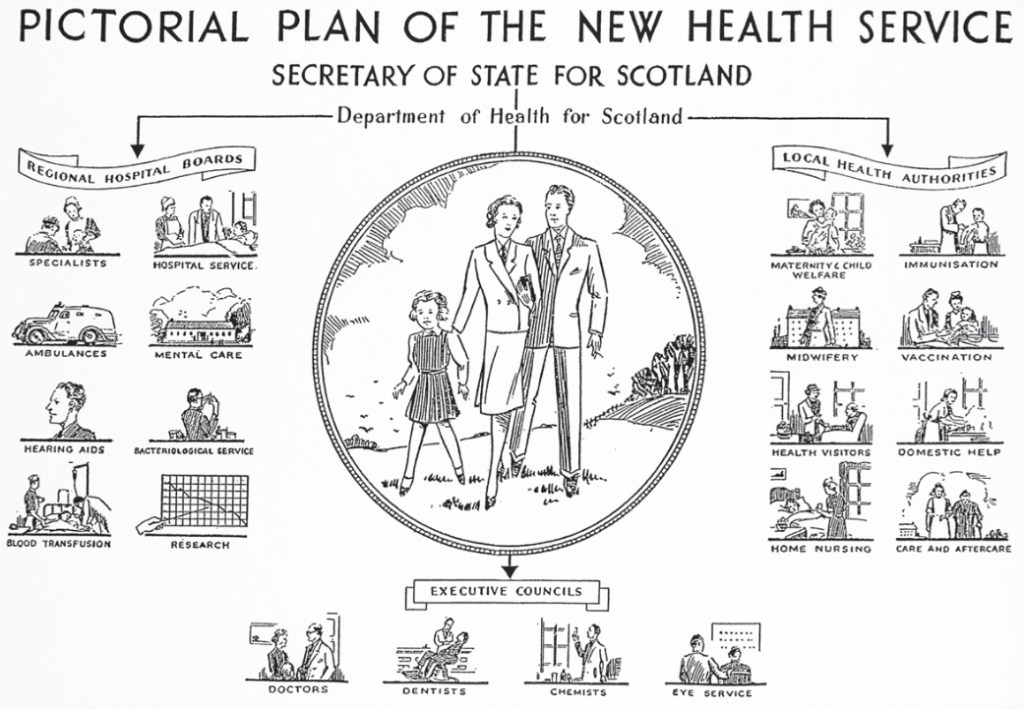

https://wdc.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/health/id/1811

https://wdc.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/health/id/817

SMA blog

(ps post has been updated to accommodate key pictures!)

Check out;

https://sochealth.co.uk/18161-2/blog

https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.275849/page/n1/mode/2up

https://wellcomecollection.org/works/ywvvazzu/items

https://archive.org/details/statedoctor00webbuoft/page/vii/mode/1up

Leave a comment